When Gayatri Kaimal, a seventh-grader from Tucson, Arizona, competes in the National Geographic Bee finals this weekend, she’ll be one of the only four girls on stage.

Fifty-four geography-loving fourth-to-eighth-graders have earned a spot in the televised, rapid-fire contest — winners of local competitions from each U.S. state and territory — but just four of them are girls. The gender gap has persisted since the competition started in 1989; of the 29 winners, only two have been girls.

Gayatri, 13, who beat 100 other children to win this year’s Arizona Geographic Bee, said geography has come easily to her ever since first grade, when she became curious about a map in her father’s bedroom. She said she feels extra pressure to perform this weekend as one of the few girls to make it this far in the competition.

“I wish there was a little bit more representation for both genders,” she said. “I don’t really want to let them down. I want to show that we are just as capable.”

The National Geographic Bee’s gender imbalance puzzles teachers, parents and students. Some say that the tournament is fair but that educators need to actively foster geographic curiosity in girls, while others think the National Geographic Society is in violation of Title IX and needs to overhaul the bee’s design to promote better results for girls.

Lynn Liben, a professor of psychology at Penn State University, studied the bee’s gender gap and found that boys and girls entered the competition at similar rates in their elementary and middle schools at a ratio of 104 boys to 100 girls. This suggests that it’s during the contest itself that the number of girls dwindles.

With map reading at its core, geography is considered a spatial subject, and boys tend to have a slight advantage in spatial skills, according to research by Liben and a geographer at Penn State, Roger Downs. Though there is a school of thought, advanced by a York University psychology professor, that evolution plays a part in this difference — with the survival of hunter-gatherer males depending on their directional skills — Liben disagrees. “You shouldn’t start out with the assumption that girls are fundamentally, biologically different from boys,” she said.

Rather, she believes cultural factors push boys into the spatial realm. Parents play with their boys and girls differently, research has found, and are more likely to emphasize stories about exploring, war and battles with boys — all of which involve maps and thinking spatially.

“When girls read military history, they also have increased knowledge of this stuff,” Liben said. “It’s not that they’re not equipped to do it. It’s just that boys do a little more of it.”

The National Geographic Society does not track statistics on the gender of students who participate in the bee. “We are always looking at ways to expand the competition's reach to inspire new audiences,” the group said in an email. “Our focus is on ensuring the competition is fair and open to as many students as possible, and promoting geographic literacy among students across the United States.”

The gender disparity doesn’t exist in the original “bee,” the Scripps Spelling Bee, which has seen 50 female and 46 male winners, according to the Scripps Bee website.

The disparity in the geographic bee was part of the reason Eric Clausen, a geologist and former director of the North Dakota Geographic Alliance, sued the National Geographic Society in 2009. He claimed a violation of Title IX, which forbids exclusion of participation in any federal education programs based on sex. It was a tough argument to make, Clausen said, given that the National Geographic Society is privately funded. Though he tried to argue that the society uses public schools for its bees and federally paid teachers as administrators, the judge threw out the case.

Clausen also has another criticism of the competition, which is that its format — a verbal, knockout contest in front of crowds with a judge, a timekeeper and a scorekeeper — is nerve-wracking and not conducive to learning.

“They’re asking them to rapidly regurgitate memorized answers,” he said.

Rote memorization is important. To win this year’s New York and New Mexico State Bees, respectively, students had to know that Georgetown is the chief port city in Guyana, and that Europe’s longest ice bridge connects the island of Hiiumaa to the mainland of Estonia.

But some answers require applying geography to real-life situations. One question this year asked which out of three locations would be best for a new ski resort, based on annual snowfall, ease of access to an airport and closeness to a population center.

David Sadker, a retired professor emeritus of education at American University, says schools can help close the competition’s gender gap by emphasizing female leaders in science and environmental fields, like Rachel Carson and Jane Goodall, in addition to discussing male explorers and conquerors.

“There are leaders who can become part of the curriculum, so girls can see themselves as having a place in that world,” Sadker said. “If they don’t see themselves as having a place, why should they care?”

Molly McHale, 11, one of the six girls who competed in the New York State Bee, said she got interested in geography after she aced a quiz in third grade. It’s now her favorite subject because it’s relevant to the news: “If something happens in the world, learning about geography would help me understand why it happened. Like, why a lot of earthquakes happen in California.”

But many of her friends, she said, are more interested in hobbies like sports, singing and dancing. “They don’t really want to study,” she said, “because they’re like, ‘It’s gonna get really boring, and it’s gonna be like school, studying for a test.’”

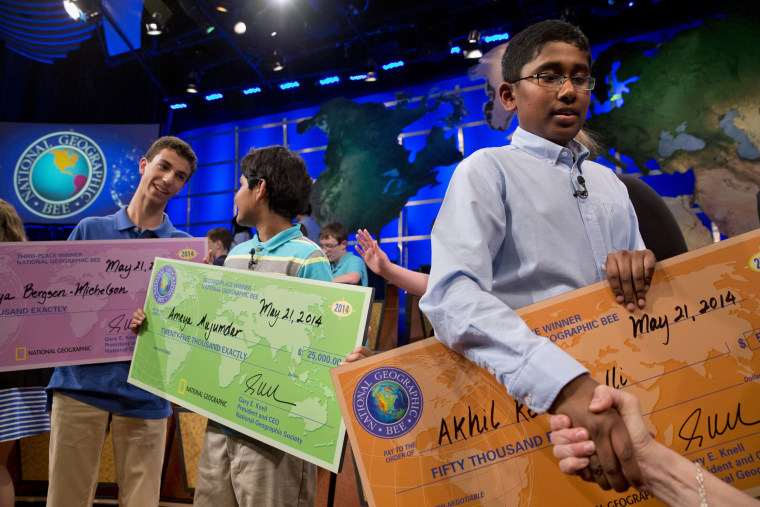

Molly has made it to the state competition two years in a row, and this year she nearly made it to the top 10, but she got a multiple-choice question wrong: Which of these processes lowers the use of irrigation? (The answer was xeriscaping.) Molly hopes to go to nationals in the future, where this year the grand prize is a $50,000 scholarship and a trip to the Galápagos Islands.

One of the four girls vying for that prize on Sunday will be Anoushka Buddhikot, 13, an eighth-grader from New Jersey who won her state’s bee. She developed an interest in geography at age 2, when she was given map puzzles of the U.S. and the world, said her mother, Aparna Kalbag. Anoushka has always had a good visual memory and excels at finding lost objects, her mother said.

As Anoushka prepared for the National Geographic Bee, her mother said that she tried not to think about the competition’s gender gap.

“Sometimes she will tell me: ‘Don’t bring it up that I’m the only girl in the room,’” Kalbag said. “She doesn’t like the gender labeling. For her, she won because she was good. Because she studied enough.”