In December 2021, the flight crew of a 737 Max 8 jet descending on autopilot from the skies somewhere over the United States momentarily lost control when it “rolled violently to the right” without warning, the plane’s captain recounted.

The first officer acted fast, disengaging the autopilot, and recovered control of the airplane — all within about a second. The plane landed safely with no other problems.

The unidentified plane’s sudden uncommanded bank, at an angle of about 30 degrees, was enough to prompt the captain to submit a report to the Aviation Safety Reporting System, a NASA-run repository shared confidentially among front-line aviation personnel worldwide and available publicly with identifying details removed.

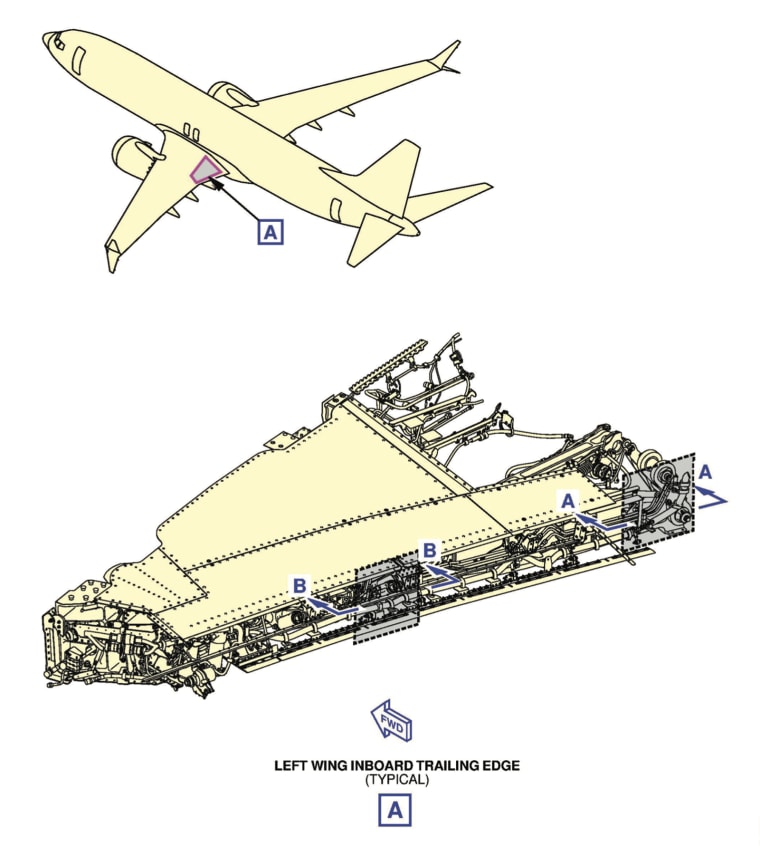

In the report, the pilot wrote that a control panel warning lit up during the incident, signaling a problem with the airplane’s left-wing spoiler — a hinged plate on top of the wing that can be lifted to cause drag and slow the aircraft. It wasn’t the first time the problem had happened, the captain added.

“This exact scenario was previously written up in the logbook multiple times in the preceding days,” the captain noted.

The 2021 incident bears striking similarities to ones that prompted the Federal Aviation Administration to propose a rule last week to require that operators inspect the wings of about 207 737 Max airplanes in the U.S. for wiring damage within three years. It’s another in a string of manufacturing and quality control troubles to emerge publicly that have haunted the 737 Max line, thrusting Boeing into crisis.

Details from the report that described the spoiler problem 27 months ago haven’t previously been reported. Neither have details in two “service difficulty reports” about incidents in two planes that were submitted to the FAA in December 2021 and November 2022.

All three reports, which aviation experts reviewed for NBC News, appear to closely correspond with what the FAA publicly identified in its proposal last week as an “unsafe condition” that could result in a “loss of control” of certain Boeing 737 Max jets because of “nonconforming” installation of spoiler control wires. Two of the three reports noted an uncommanded rightward roll, coupled with the spoiler warning light. The third didn’t involve a roll, but it described issues similar to what the FAA says is “the root” of the problem described in its proposal: chafing of the wires controlling the spoiler.

The FAA proposed rule, known as an airworthiness directive, cites a single report about one airplane that experienced “multiple unusual deployments” of spoilers during several flights, adding that an investigation found spoiler wire bundles became chafed because of contact with the aircraft’s internal wing structure. It said the condition is “likely to exist or develop on other products of the same type design.”

The FAA’s move comes eight months after Boeing sent a service bulletin in July to operators of about 860 potentially affected 737 Max-8 and -9s worldwide, providing them with instructions to perform voluntary inspections of wire bundles in their fleets.

Boeing first notified operators about the potential spoiler issue in May 2022, and it “developed a solution” in the Max production line in June 2022 that addressed the problem on new planes, spokesperson Jessica Kowal told NBC News.

The steps Boeing has taken and the FAA’s rulemaking process demonstrate that “this is not an immediate safety-of-flight issue,” Kowal said.

But four aviation experts — a former Boeing 737 factory manager, two retired FAA safety engineers and an ex-airline captain who flew 737s — said in interviews that they believe the problem is serious and requires more urgent attention.

“I think it’s extremely significant, and I think Boeing and the FAA are not putting sufficient priority on it,” said Joe Jacobsen, a retired FAA engineer who has served as a technical expert to Congress and as an FAA technical representative on National Transportation Safety Board accident investigations. “It should be inspected as soon as possible.”

The FAA declined to answer questions about its proposal for this article, saying in a statement only that it bases its “compliance times on the risk from the issue that’s being addressed.” The agency said it will “consider all relevant public comments” through late April before it finalizes the proposal.

Captain John Cox, a former commercial airline pilot and founder of an aviation safety consultancy, said the problem demonstrates “yet another case where an airplane got out of the factory with a defect or an improperly executed task and it wasn’t picked up.”

“That, in light of the other issues that we’ve seen recently from Boeing, is the most concerning to me,” he said.

While it still faces legal and reputational fallout from two Max crashes that killed 346 people five years ago, Boeing came under new scrutiny this year after a panel blew out of a 737 Max 9 and left a gaping hole mid-cabin during a crowded Alaska Airlines flight in January.

The incident prompted the FAA to temporarily ground some models of the plane and issue an emergency airworthiness directive requiring immediate inspections.

By contrast, Kowal said, the spoiler issue “has been identified as a safety issue longer-term," giving operators up to three years to inspect the planes.

Kowal declined to answer questions about exactly when Boeing first learned of the issue or provide details about the aircraft that prompted internal analysis of the problem.

Boeing isn’t sure how many operators have already voluntarily performed inspections, Kowal said. At least one, SunExpress Airlines, has submitted a comment to the FAA seeking credit for having already performed the voluntary inspections once the proposal becomes mandated.

“This issue isn’t new or an emergency,” Kowal said.

But until the FAA published its proposal along with Boeing’s July service bulletin last week, the public knew nothing about the matter, said Ed Pierson, a former manager of Boeing’s 737 factory who now heads the nonprofit advocacy group Foundation for Aviation Safety.

“The FAA is just now reporting it,” Pierson said. “Not even reporting it — we’re learning about it through a federal rule-making process … under the guise of informing the public.”

“You would think people would want to know,” he added.

Cox, the former commercial airline pilot, said he believes most trained commercial airline pilots confronted with such a rogue spoiler deployment in flight could overcome the problem.

“I can see places where it would be fairly serious, you know, like in the process of landing,” he said. “But 737s have so much roll control. It’s one of the real strengths of that jet.”

An uncommanded spoiler deployment “could make for a hard landing or something like that if it happened at the exact wrong time,” he added. “But that window is really short. It could be a handful, but I think that it would be controllable.”

Cox said he believes the FAA proposal calling for inspections of hundreds of Maxes is the appropriate way to address the problem. But he added it’s surprising how long it took Boeing, and then the FAA, to address the issue after they learned about it.

“Any time you have an uncommanded flight control movement, it’s serious,” Cox said. “So for something like this, I would like to think they’d move faster than that.”

Asked about the time it took Boeing to respond, Kowal said that in general, when an issue is reported in the fleet, an engineering analysis is conducted to identify a root cause and determine safety implications and production issues. All of that takes time, she said. The FAA then has its own regulatory pace and process, she said.

Specific to the spoiler issue, Kowal said: “The chafing happens at a very slow rate; this was identified in the fleet on one airplane.”

But one of the reports NBC News reviewed suggests that wire chafing occurred on a relatively new plane, and states that it might have happened during production.

Kowal didn’t address the specific reports identified by NBC News for this story, saying only that “any issue that Boeing becomes aware of is assessed from a safety perspective with the FAA.”

Mike Dostert, a retired FAA engineer who has studied wiring problems that caused airplane accidents, said wire wear rates are unpredictable because of a host of variables that can occur during installation.

“In my experience, it’s not an exact science,” said Dostert, who wrote multiple airworthiness directives during his career.

“They need to get these things fixed quickly,” he added. “We shouldn’t be taking long times, especially years, to address potentially catastrophic, unsafe conditions. Why take the chance?”