LOS ANGELES — For a few months in 2009, Desiree Townsend was famous.

Back then, she was known by her married name, Desiree Jennings. But most who remember her at all today would know her as some version of “Flu Shot Cheerleader.”

The short version of the story goes like this: Desiree was a beautiful cheerleader who believed her seasonal flu shot triggered a mysterious injury. News coverage of Desiree’s new disability — mostly her twisted, jerking gait that disappeared when she ran or walked backward — went viral, and leaders of the anti-vaccine movement embraced her as a new poster girl, in the mold of model spokesperson Jenny McCarthy.

But Desiree’s seemingly inexplicable symptoms set off a national debate over whether she should be believed. And almost as quickly as the media and the anti-vaccine movement had elevated her, they turned. Branded a faker, her illness a hoax, Desiree all but disappeared.

Fourteen years later, Desiree wants to talk about it. She felt ashamed for a long time, but now she sees things differently. Her symptoms were real, she says, and life-altering. She’s far less certain about the role the vaccine played.

What she really wants to talk about, though, is the anti-vaccine movement’s “PR machine” — how she says it seized on her story at a moment when she was ill and the professionals who were meant to provide answers couldn’t explain her suffering. She wants to talk about how the movement discarded her when she became inconvenient, and left her to weather the storm that followed alone.

And she wants to offer a warning. Desiree’s story is one of the earliest and best-known examples of the kind of unproven and emotionally-charged accounts that power the modern anti-vaccine crusade. What happened to her is especially relevant now, when the movement is arguably at the height of its power.

Misinformation and unfounded fears over vaccines soared during the Covid pandemic. The movement’s de facto leader, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is running for president, peddling his conspiracy theories and debunked pseudoscience to an enormous new audience. Childhood vaccination rates have fallen, and the largest anti-vaccine groups are overflowing with cash.

The main characters in Desiree’s story have shifted — the ones who died or moved on have been superseded by a new crop of organized and aggressive players. But the tactics are the same: Find novel stories from vulnerable people who say they’ve been harmed and blast those stories to a hungry and ever-expanding following as proof for unscientific claims that stoke distrust in vaccines.

“At the end of the day, these people are just going to use you,” Desiree says of the movement that recruited her. Her advice for the people getting caught up with it now?

“Run.”

In August 2009, Desiree was a 25-year-old communications manager at America Online, newly married and a cheerleader ambassador for the football team now known as the Washington Commanders. (The team paid her a small salary not to cheer, but to look like a cheerleader, wear a slightly more modest uniform, and interact with fans in luxury suites.)

She went to a local pharmacy in Virginia for a seasonal flu shot, and about 10 days later, she felt sick. Her initial symptoms — fever, vomiting and weakness — quickly turned more serious: Her body shook uncontrollably and she was blacking out. Desiree attributed her body’s revolt to the vaccine.

The following account is based on media coverage from the time; interviews with Desiree, her former colleagues and family members who asked that their names not be used to avoid any negative fallout; a 236-page special federal court decision dismissing her vaccine-injury claim; and video recordings made by the anti-vaccine organization Generation Rescue for an intended documentary, which Desiree provided to NBC News.

Desiree spent the next month in and out of hospitals and doctors' offices seeking treatment for a cornucopia of problems: She was dizzy and constantly tired. She couldn’t sleep, walk, or eat without getting sick. She had chills but also burning in her arms and legs, which started to jerk uncontrollably. Her speech was slurred. Her head ached. A former colleague remembered how different Desiree became from the vibrant, thriving woman she had worked with for years. “Desiree was the healthiest person you knew,” she said, “and then suddenly so sick.”

Desiree’s symptoms were, according to the notes of one neurologist who treated her at the time, “extremely peculiar.” She saw neurologists, emergency room physicians, cardiologists, primary care physicians, infectious diseases specialists and rheumatologists. They tested Desiree’s blood and ordered MRIs, spinal taps, chest X-rays and EKGs, looking for lupus and Lyme disease and Guillain-Barré syndrome and dozens of other possibilities.

In the end, several doctors suggested that in the absence of any other explanation, the cause of Desiree’s strange condition might be “psychogenic,” meaning not that she was faking her symptoms, but that they were resulting from stress or some underlying psychological condition. They suggested she see a psychiatrist. A physical therapist separately mentioned dystonia, a neurological movement disorder that can cause involuntary muscle spasms.

Dr. Daniel Freedman, a pediatric neurologist in Austin, Texas, treats children with functional neurological disorders (previously known as psychogenic neurological disorders) and said they “often feel victimized by the health care system.”

Desiree updated her friends and family on her condition with posts and videos on Facebook, claiming that doctors had landed on dystonia and linked it to the flu vaccine. (That diagnosis was not reported in Desiree’s medical records from the time.)

Her story made its way into a local newspaper, then local television news reports and, eventually, national news — each one repeating Desiree’s unverified claims about the vaccine, many with no pushback at all.

A friend and newly hired community blogger for Virginia’s Loudoun Times-Mirror first wrote up Desiree’s version of events in a column. Within two days, TV news reporters from local NBC, CBS and Fox stations had picked up the story. The TV tabloid newsmagazine “Inside Edition” followed with a segment that showed Desiree’s symptoms: She stomps, then squats. Her arms twist and flail. She almost falls, but then doesn’t. Her speech is slow, slurred, her voice monotonous and nasal. Then Desiree walks backward and her strange symptoms melt away. She talks normally, walks straight.

“Her jerking and twisting are the result of uncontrollable muscle contractions,” correspondent Les Trent says. “There is no known cure.”

Within the week, Desiree’s story had gone viral, videos of her TV appearances racking up millions of views.

That story — a pretty cheerleader, strangely disabled by a vaccine — was ratings gold. “Inside Edition” host Deborah Norville called it “one of the most talked-about stories we’ve ever had.” But the coverage was met with doubt from doctors, who took to professional listservs and blogs to state that whatever was going on with Desiree, it wasn’t dystonia.

Dr. Paul Offit, the director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine, was one of the skeptics.

“When I first saw that video, I felt so badly for her,” Offit remembered. “I thought, ‘Oh, God, this is going to be so hard for her.’”

For all the trips Desiree made to various doctors, she wasn’t getting answers. And she didn’t feel like they understood. She couldn’t keep food down. She couldn’t walk. She couldn’t work.

“It was so frustrating, because the doctors would ignore me,” Desiree said. “They made it seem like I was an idiot, or I was crazy, or it was just stress.”

But there were others, who Desiree instantly felt did believe her. They told her they knew what was wrong and that they alone could fix her.

The media storm around Desiree came at a time when the country was already on edge, in the midst of a pandemic — a novel H1N1 flu that would ultimately infect some 60 million Americans, and kill more than 12,000 that year.

Swine flu was a boon for the anti-vaccine movement, which had suffered in recent years: Its leading researcher had been discredited, the theorized link between autism and vaccines disproven, and confidence in childhood vaccines was high. But this new outbreak, which disproportionately affected children and pregnant women, would revive the cause, providing an opportunity for anti-vaccine activists to expand their message beyond early childhood vaccinations.

By fall, an H1N1 vaccine was available. But some 40% of the country didn’t want it. Nearly two-thirds of U.S. parents said they were either waiting or refusing to have their children vaccinated against swine flu. Part of the reluctance was due to worry that the vaccine had been rolled out too quickly, that it hadn’t been tested enough. (The swine flu vaccine was formulated and manufactured using the same process as seasonal flu shots, and it had gone through clinical trials, but fears persisted.)

A new, highly organized and extremely online effort was taking advantage of the moment; its most visible leader was celebrity activist Jenny McCarthy and her organization, Generation Rescue. McCarthy; Generation Rescue’s founder, J.B. Handley; and the organization’s then-president, Stan Kurtz, all had sons with autism, which they said had been caused by vaccines. They also said their sons were being cured with special diets and unproven biomedical treatments.

As McCarthy and then-partner Jim Carrey led marches and hosted fundraising galas, Kurtz lectured at conferences and handled recruitment. A big part of that effort involved mining the internet and local news reports for stories about people who believed that they or their children had been injured by vaccines.

Kurtz saw the local news coverage and contacted Desiree.

“The story is just, anyone that sees it, it’s just so compelling. Jenny was crying,” Kurtz told a reporter for the local Fox station, before announcing that Generation Rescue would be helping Desiree “recover” from her vaccine injury.

So Desiree hitched herself to Generation Rescue. They helped her set up a website, which advertised a Kurtz-owned vitamin lollipop business and other products affiliated with Generation Rescue and its board members. Meanwhile, the organization put out a statement challenging the doctors on TV who dared doubt her and raised money via its own website “to help pay for her mounting medical expenses.” (Desiree said she never received any of it.)

Desiree’s experience, the group wrote, “in many ways, parallels the experience of our children, who many of us watched regress into autism after the administration of multiple vaccines.” Desiree echoed this “for the children” language on her blog and in news interviews. “I want to speak because I can and they can’t,” she told Fox5.

“I felt obligated to buy into what they were saying,” Desiree told me. “I didn’t know anything back then.”

Kurtz came to her home in Virginia with a camera crew, which over the next week captured over 40 hours of video — the makings, they said, of a future documentary, warning against vaccines, starring Desiree.

The documentary was never made.

The footage shows Kurtz accompanying Desiree to North Carolina that October for treatment by Dr. Rashid Buttar, an osteopath popular with the anti-vaccine crowd for his advertised miracle cures for everything from autism to cancer — hyperbaric chamber therapy and mercury chelation that he claimed could “detox” patients of the heavy metals vaccines had left behind.

Those therapies have proven uses. Hyperbaric therapy is used for scuba divers who get the bends and people with carbon monoxide poisoning and wounds that won’t heal. Chelation involves IVs of a medication that treats heavy-metal poisoning. But Buttar used chelation and hyperbaric therapies on autistic children and Desiree. There is no evidence that such treatments are effective for autism, and they come with dangerous potential side effects, research shows.

(In 2010, the state medical board reprimanded Buttar following patient complaints that he charged exorbitant fees for ineffective cures.)

In a video of her arrival at Buttar’s office, Desiree, lying curled on a table, convulses and then goes limp. A television on a rolling cart plays a Buttar-produced propaganda film about the dangers of vaccines, as Kurtz feeds Desiree applesauce and strokes her back.

Over the next several days, Buttar treated Desiree with IV chelation therapy, vitamin cocktails and a lotion chelator rubbed on her arms. In a room painted in an under-the-sea motif, Kurtz follows Desiree into a hyperbaric chamber, where Buttar says the pure oxygen will relieve inflammation in her brain. Forty-eight hours later, Desiree appears noticeably better — talking normally and able to sit on her own, her tremors stopped. “You’re a miracle worker,” she tells Buttar.

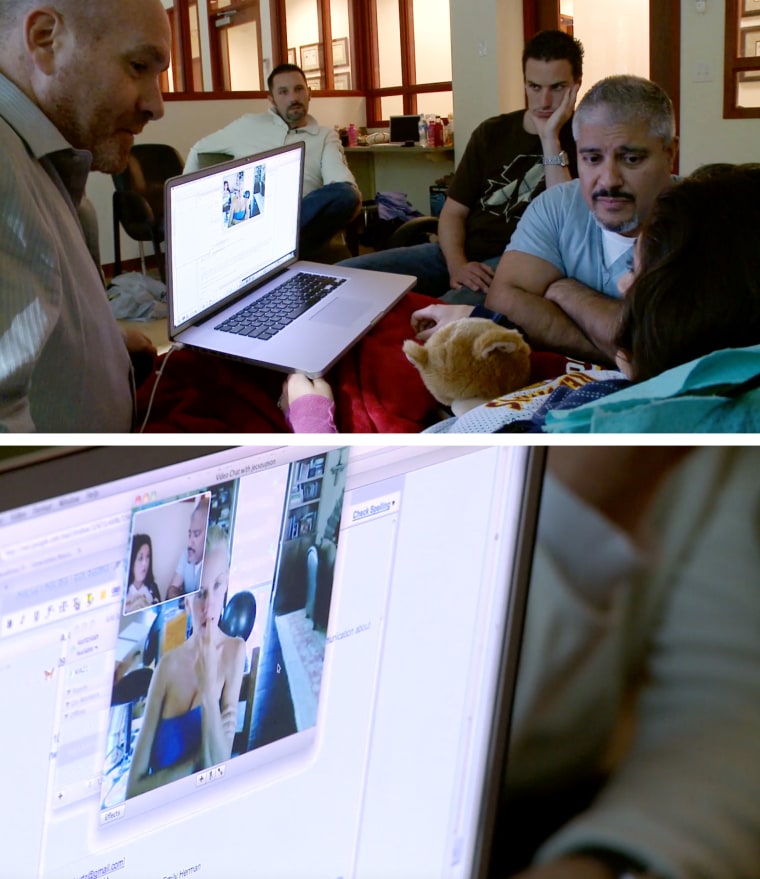

They call Jenny McCarthy over video to tell her the good news. Had Desiree not come to his office when she did, Buttar says it “would have been the end.”

In another taped conversation where Desiree is not present, Buttar and Kurtz consider what Desiree could mean for their movement and Buttar’s practice.

“This is good,” Buttar says. “She’s going to make a huge ruckus where it’s needed.”

“She’s another budding Jenny McCarthy,” Kurtz says.

But Kurtz wasn’t stopping with Desiree. As she received treatment, Kurtz was on the lookout for other prospective spokespeople. Just that week, he had commented on an online memorial page for an 8-year-old boy, Sean Weisse, who had died about a week after receiving a seasonal flu vaccine: “We are so sorry to hear about Sean. My understanding, and forgive me if I’m wrong, is that this was a vaccine-related injury. If so, we would like to help you.”

While at Desiree’s bedside, the documentary team recorded Kurtz emailing a woman in Phoenix who had been the subject of a local news story on her reported allergic reaction a month after tetanus and flu shots. Under the subject line, “Ultra Confidential,” Kurtz wrote, “We have a particular amazing opportunity to not only truly heal you, but to let the world know what is going on.”

A week after Desiree’s first treatment, Buttar and anti-vaccine websites were claiming that she had been healed. But back home, Desiree’s symptoms recurred, and she had a new one: She was now talking with a British or Australian accent. In December, Desiree saw a neuropsychologist who wrote: “She would do well to avoid the pull toward being a public spokesperson for others and instead focus on her own wellbeing and rehabilitation. It is clear that stress exacerbates her symptoms.”

The relationship between Desiree and Generation Rescue was short-lived anyway. In part, that’s because four months after its original story on Desiree, “Inside Edition” went back to Virginia. Producers had been staking out Desiree’s home in January, taping her playing with her dogs, walking normally and driving. The segment’s climax was an ambush interview in which Desiree was painted as a faker.

“Inside Edition” was followed by a “20/20” investigation titled, “Medical Mystery or Hoax?”

“You decide,” Chris Cuomo told viewers, “whether she’s a victim or a fake.”

The internet responded as it does: by making fun of Desiree, creating viral mashups overlaying the “Inside Edition” tape with songs like “Walk It Out” and the “Benny Hill” theme. They dubbed her “Wobble Girl.”

“She keeps a lot inside,” Desiree’s little brother, who was living with her at the time, said in a recent phone interview. “But I think it broke her heart.”

Kurtz stopped calling. Generation Rescue refused to pay Buttar’s $32,000 bill, Desiree said, and quietly removed Desiree’s story from its website.

Desiree deleted all of her social media accounts. She moved to California, got a divorce and changed her last name to Guerriere, after the French warship.

“I didn’t really know what else to do, but run and hide,” Desiree said.

Still the story lived on, its impact hard to quantify.

Handley, Generation Rescue’s founder, described Desiree’s influence in a 2010 interview with “Frontline”: “You have an image of this beautiful woman who’s been severely disabled that literally tens of millions of people view overnight, and imagine the chilling effect that has on a flu vaccine that she attributes as the cause of her condition. It’s remarkably powerful.”

Offit, who publicly speaks about the science behind vaccines, said her message reverberated through the vaccine-hesitant. He was approached by people at talks, he said, concerned about what they had seen.

“People would tell me they were horrified and scared this would happen to them,” he said. “They believed that a bout with influenza would be better than the chance of having this happen.”

In a 2010 survey from Virginia Tech, several students reported Desiree as a reason they distrusted the flu vaccines.

“I had no idea that my story led to people not receiving a vaccine,” Desiree said. “I thought that people just thought I was crazy. But if I caused anyone to not receive a vaccine, or put their children at risk or themselves at risk? I feel an immense amount of guilt for that.”

“I was just taken advantage of,” she added. “I needed help.”

Fourteen years later, Generation Rescue is no more. It ceased operations in December 2019, according to its final tax filing. Handley — who did not respond to requests for comment — has moved on; he currently advocates for a technique called Spelling to Communicate, which posits that nonverbal autistic children can communicate with a facilitator using a letter board. Experts call it pseudoscience.

McCarthy — who did not respond to requests for comment — is a judge on Fox’s “The Masked Singer,” and though less involved, still pops up to support anti-vaccine causes.

Kurtz runs a sourcing company, Quantum Technology, and is part of his son Ethan’s team on Discovery Channel’s “BattleBots.” “I’ve been out of this space a long time,” Kurtz said by text. “I’m not sure there is a benefit in me commenting.”

Buttar’s family emailed supporters in May to say he had died; a cause of death was not disclosed. Anti-vaccine conspiracy theorists have suggested Buttar was killed for spreading disinformation — which they see as truth — including the false claim that Covid vaccines would kill most of the people who took them. His family and office did not respond to requests for comment.

Desiree’s experience came from the early days of social media, during a pandemic that proved mild by today’s standards. Covid brought forth hundreds of people like Desiree — posting unverified accounts of strange reactions attributed, they said, to the vaccines. And new Generation Rescues — organizations like Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Children’s Health Defense, ex-daytime TV producer Del Bigtree’s Informed Consent Action Network, and the Vaccine Safety Research Foundation, founded in 2021 by veteran Silicon Valley entrepreneur Steve Kirsch — were eager to amplify the testimonials.

Freedman, the pediatric neurologist from Austin, warns against rushing to judgment. He said people pushed away from mainstream medicine often fall “into quackery and anti-vaxx circles.”

“These are people who are suffering,” Freedman said of people in the so-called vaccine injury videos. “If we humiliate them and alienate them, they’re definitely not going to get the help they need.”

In 2011, Desiree filed a complaint in a special federal proceeding whereby people are compensated for vaccine injury claims. In 2019 — eight years, 59 doctors, two psychologists and 289 exhibits after it was filed — Desiree’s case was dismissed.

In her decision, the special master, who acts as a judge for what’s colloquially known as vaccine court, wrote, “The evidence in this case as well as the more persuasive opinions of respondent’s experts and supporting medical literature show that petitioner did not have an adverse reaction to flu vaccine.”

Desiree, who took the last name of her longtime partner years ago, went back to school and graduated in 2019 from the University of California, Irvine, with a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and molecular biology. A fascination with vaccines became a professional dream: to work for a biotech company that manufactured them. When the Covid vaccine became available, she took it, and a booster.

She’s seen dozens of doctors over the last decade, tried nearly as many treatments and medications, and by 2016, most of her symptoms had resolved, enough at least that she could work and start school again.

Tests administered by her doctors brought Desiree close to an explanation for what happened to her back in 2009. She believes a dormant autoimmune disorder was triggered by something. Maybe it was the multiple bouts with bronchitis the year before everything started, or the fact that she was over-exercising, eating terribly and guzzling energy drinks. Maybe it was stress. Maybe, she still wonders, it was the vaccine. Or maybe it was something else entirely.

“I’m not going to ruminate on it,” she said. “You have to be open to other possibilities, right? And sure you could argue that there may have been a psychogenic component. When your whole life is falling apart, you’re losing your career, your body’s failing, you’re being pulled into this media stress. I’m sure there was probably some component of stress involved that exacerbated the symptoms.”

These days, Desiree feels good. She neither has, nor wants, children. She spends time with friends and still runs whenever she gets the chance. She’s testing the waters on LinkedIn and Instagram.

As for her health, she has a strict regimen for diet and exercise. She sees doctors. She takes medicine.

“I’ve gotten a good hold of the beehive that lives inside of me, and I know what keeps them happy, and I just stick to that program,” she said.

But her former life is never far.

A popular comedy podcast recently found the lengthy decision from vaccine court — and even though the document only identifies Desiree with initials, it’s clearly about her. The hosts spent 81 minutes in September delving through her most private and embarrassing medical history. They said she was “clearly lying” and called her a “scammer.”

When Buttar died this year, Desiree said a media organization reached out to her for comment. She felt like she should let her employer know who she was. When Desiree told her boss at a Seattle biotech startup, she said she was asked to resign. Desiree is looking for a new job in Los Angeles and has been on a few interviews. She’s hopeful.

For the anti-vaccine movement, Desiree was the start of a fresh chapter of a playbook that’s still in use today. But she was a blip, a story that emerged at the beginning of a new media age and a moment of opportunity — quickly seized upon and then buried. She remains cemented in popular culture, and her videos go through waves of virality still. Every so often, Desiree is recalled or newly discovered, and a whole new audience gets to weigh in.

Desiree is a little nervous about this story. She’s still embarrassed. Friends have told her not to talk to the media again, and sometimes she thinks she shouldn’t, too. But those thoughts are fleeting. “I’m not scared anymore,” she said.

She’s not naive either. She knows there are people, maybe most who remember her, who thought she was faking in 2009 and won’t believe her now.

“That’s fine,” she said. “You just have to tell your story and let the cards fall.”