It’s a fundamental principle of American life: People accused of wrongdoing have a chance to defend themselves. They’re innocent until proven guilty.

That is, unless they’re a child attending a public school.

An NBC News investigation into student discipline policies found that children’s ability to fend off deeply damaging punishments depends on where they live or where their parents send them to school.

In much of the country, districts offer students facing suspensions or expulsions only the most basic legal protections required by a 1975 U.S. Supreme Court decision: Schools must tell students what they’re accused of and give them a chance to respond before, or soon after, removing them from class.

Other legal protections — like the right to bring an attorney to a disciplinary hearing, the right to see the evidence against them before their hearing, and the right to call and question witnesses — are not guaranteed for students in every state.

Alabama, Nevada and Virginia are among states that do not specify these rights in state law. Instead, they give schools broad authority to decide which protections students should have before they’re kicked out for weeks, months, a year — or, in some cases, forever.

“The sad reality is you can remove kids from school for very long periods of time in some states with minimal due process,” said Harold Jordan, the nationwide education equity coordinator for the American Civil Liberties Union, noting that even in states with more legal protections, students whose families don’t hire a lawyer may not understand their rights or be able to assert them. “Schools know that they can get away with it.”

The result: Students like Jo’anna Tatum, 11, of North Las Vegas, have been punished for things they didn’t do. The sixth grader was accused in January of hitting an administrator, suspended from class and recommended for an 18-week expulsion after a brief meeting with an assistant principal who told her the matter was “out of his hands,” her mother, Shairome Reece, said.

Reece said she didn’t see witness statements that showed her daughter had not struck the administrator until two months later, just before a district discipline panel convened a formal expulsion hearing. At the hearing, the same assistant principal testified that it was another girl — not Jo’anna — who hit his colleague.

The panel allowed Jo’anna to return to school, but, by then, she’d missed so much class that she was struggling socially and academically.

“I feel like they don’t really care,” Jo’anna said. “They’re not fair to all kids.”

The Clark County School District in Las Vegas did not comment.

Nationally, more than 101,000 students were expelled and 2.5 million suspended in the 2017-18 school year, the most recent year for which federal data is available, and many fear those numbers have climbed since the pandemic.

Decades of research has shown that suspensions increase a student’s odds of dropping out of school or ending up in the criminal justice system. These punishments have long been imposed in deeply inequitable ways, with one recent report finding that 27% of Black boys with disabilities were suspended from U.S. middle and high schools compared with 7% of students overall.

NBC News interviewed 31 lawyers and advocates who have collectively represented hundreds of students in suspension or expulsion matters as well as the parents or guardians of 41 students who were suspended, expelled or sent to alternative schools in recent years.

They described a system in which parents are informed of how their children will be punished without any inkling that they can object, leaving students feeling powerless, like the system is rigged against them.

Some of these parents said their children were disciplined without getting to plead their case in a hearing. They were banished to online classes, arrested, sent home, or encouraged to transfer to other schools in order to avoid punishment.

Seven of the parents who spoke to NBC News said they weren’t allowed to see the district’s evidence against their child before their hearing. Eight said they had no way to challenge statements made by their children’s accusers, and three said their schools barred them from presenting evidence they believed would prove their child’s innocence.

School leaders say they rely on suspensions and expulsions to address difficult, dangerous and disruptive behaviors. Without sufficient resources to address the complex challenges driving student misconduct, they use these punishments to hold students accountable and maintain order in classrooms.

Administrators aim to be fair and thoughtful in their punishment decisions — but schools are not courts, said Francisco Negrón, the chief legal officer of the National School Boards Association.

Disciplinary hearings are about more than just a student’s guilt, Negrón said. They’re a chance for administrators to consider ways to support all children involved in an incident, including those accused of misbehaving and those who may have been harmed.

Schools need policies that work for students of all ages and for a wide variety of infractions, he said. They must consider whether due process protections, such as the right to cross-examine witnesses, could, for example, traumatize a sexual assault victim who might be forced to testify.

“That spectrum of potential behavioral challenges is what makes the school setting unique and different,” Negrón said. “It should not be equal to a criminal proceeding.”

‘They betrayed me’

Schools across the country have been moving away from suspensions and expulsions.

Responding to research showing that these punishments are ineffective, associated with higher rates of school disruption and violence as well as lower test scores, many schools have turned instead to in-school interventions or “restorative” practices that focus on students taking responsibility and remaining in class, learning from their mistakes.

These changes have led to a decline in suspension rates since 2010, but rates are still higher than they were in the 1980s, and racial disparities have persisted.

When schools make the choice to suspend or expel a student, experts say they face an uneven legal landscape. Students with disabilities have protections under federal law and some lower court decisions have afforded specific rights to students in certain states, but neither Congress nor the Supreme Court have clearly defined students rights in a way that would make them consistent across the country.

That leaves some students with few ways to object when they believe their school has treated them unfairly or was biased against them.

Kiara Dixon said her son, Xavier, received a four-month suspension from his Virginia Beach middle school last fall after a hearing examiner refused to consider evidence that the “pneumatic weapon” Xavier, 13 at the time, was accused of wielding was actually a clear, plastic toy.

“As soon as we sit down, he looks at my son and says, ‘Why did you try to shoot that kid?’” Dixon recalled of the former school administrator who presided over her son’s hearing.

In an email to district officials appealing the punishment, Xavier’s lawyer alleged that the hearing examiner had been “in a rush” and decided not to view video of the incident, which occurred outside Xavier’s home after school, choosing to look instead at photographs. The district later agreed that Xavier could attend virtual school while he was suspended, but Dixon decided to homeschool him instead.

The Virginia Beach City Public Schools declined to comment.

In Alabama, lawmakers in recent years have debated — and rejected — legislation that would require districts to give students additional rights, including a hearing within 10 school days of their removal from class and a chance to review all evidence in advance.

School leaders opposed the bill, arguing that it would interfere with how they run their schools.

“While it is a last resort, suspensions are sometimes necessary,” Ryan Hollingsworth, the executive director of the School Superintendents of Alabama, said in a statement. “Local boards of education and local communities know best what policies will be effective in their communities and that’s where these decisions should be made.”

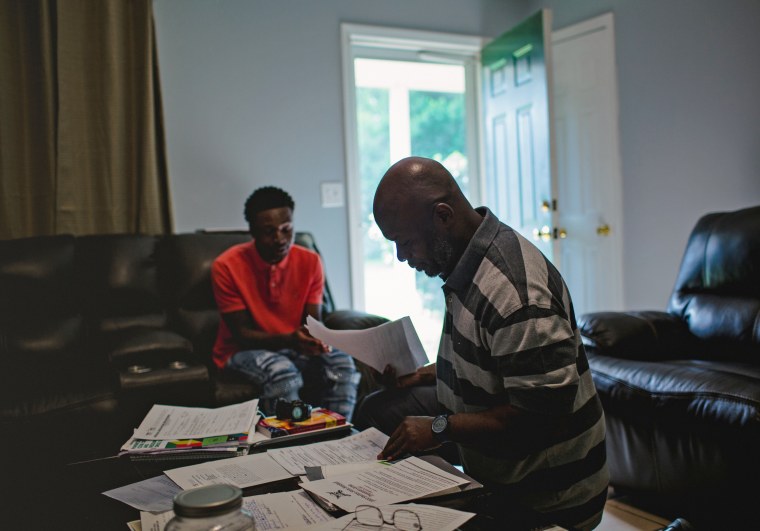

In the absence of this law, Tuscaloosa student Cory Juneau Jones Jr. spent nearly two months of his senior year in in-school suspension waiting for a disciplinary hearing after being accused of bringing marijuana to campus. Jones, who was 17 at the time, insisted the drugs weren’t his; police investigated the November incident and charged someone else, not Jones, according to his family and a police report.

At the hearing in January, according to Jones and his father, the school denied him access to the investigative report that the district said proved his guilt and declined to show him security video he believes would have cleared him.

The school ordered Jones to spend 45 school days in an alternative school — a fate he was so determined to avoid that he transferred to an online program.

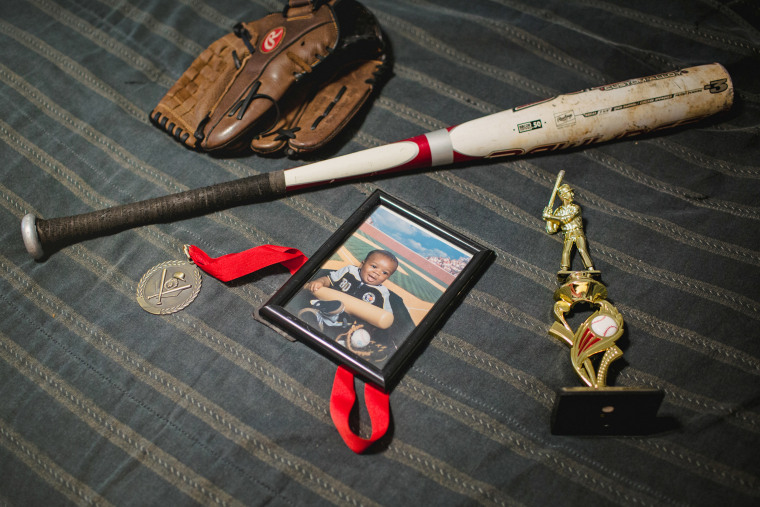

“They betrayed me,” Jones said of school administrators whose punishment meant he missed the baseball season he hoped would help him earn a college scholarship.

When his family hired a lawyer and tried to appeal, Tuscaloosa City Schools refused to allow the lawyer into a meeting with school officials, making her sit in the hallway.

The district declined to comment on Jones’ account, but a spokeswoman said in a statement that the district is “committed to following established policies and procedures” to address disciplinary issues. She added that the district cannot always share evidence with students due to privacy concerns.

Rachel Blume, Jones’ lawyer, said the Tuscaloosa district has barred her from attending client disciplinary meetings on four occasions.

“They don’t want to be challenged in their decision-making,” Blume said of districts that bar attorneys. “They’re making up their own rules and calling it due process when it’s not.”

‘It just ruined him’

As they started their senior year at Goshen High School in Pike County, Alabama, Dakarai Pelton and RaQuan Martin were both star athletes on the varsity football and basketball teams. Both had good grades and clean discipline records. Both said they’d met with college scouts and believed they were in position to win athletic scholarships.

That changed on Nov. 22, 2019, the day that Pelton and Martin — best friends — skipped class and followed a friend to her car because she said she had something to show them. Both boys say they got in the girl’s car, saw that she had drug paraphernalia, which they described as a “bong,” then quickly returned to the school.

Both boys insist that they did not smoke marijuana that day. Martin’s parents gave him a home drug test that evening that confirmed this, his mother told the district’s discipline council. Pelton’s drug test — given a couple weeks later by a doctor — also showed no evidence of marijuana use, his mother said.

The Pike County school district allows students to bring lawyers to their discipline hearings, but neither student did so. Pelton’s mother, Shatarra Pelton, said the school told her a lawyer wasn’t necessary. “They said no. It was just a review of what he was being accused of,” she recalled.

Had Pelton and Martin lived 60 miles to the east, on the other side of the Georgia line, things might have gone differently, said Michael Tafelski, a lawyer from the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights organization that represented Pelton and Martin when they later sued their district.

If the boys had been in Georgia, their district would have been required by law to share evidence before their hearings, said Tafelski, who has represented students in both states. The boys would have known that other students in the car that day had admitted to smoking weed. They would have known that the district had video evidence that showed what looked like suspicious behavior, Tafelski said, including that Pelton and Martin had exited the building through separate doors to avoid drawing attention to the fact that they were skipping class.

But, in Alabama, all of this took them by surprise.

Five minutes into Martin’s hearing, just after he professed his innocence in his opening statement, he got pushback from Mark Head, the administrator chairing the three-member Superintendent’s Discipline Council that day.

“You know that doesn’t match the other stories we’ve heard. I’m just saying,” Head said, according to audio of the hearing.

Another council member, district administrator Donnella Carter, grilled Martin about why he was so “curious” about the object in his friend’s car. “It’s going to behoove you not to be so curious in the future, you hear?” she said. She then asked him four times whether he had smoked marijuana, stressing that “we already know that smoking was going on in the car,” and seeming to doubt his repeated assertions that he hadn’t smoked.

“You’re certain that’s the truth?” she asked. “Because it’s not going to help you to come before us and be dishonest.”

During Martin’s hearing, the school principal told the council that students were in the car for five or six minutes. The council then watched the security video, which showed Pelton and Martin leaving the car before the others. The video also showed the pair dousing each other with body spray when they returned to the building — another thing the council thought was suspicious. Both boys said they used body spray because the girl’s car smelled bad. “It stank in there,” Martin told the council.

Pelton’s hearing went much the same way except that technical issues prevented him from seeing the video. Instead, Head described it. “We can’t see what happens in the car, but we know they went to the car,” he said.

When Pelton denied smoking marijuana, Carter asked if he had ever used the drug. He admitted that he had, which led council members to take turns lecturing him on the negative consequences of marijuana use.

“It’s considered a gateway drug,” Carter told him.

Had these hearings occurred in Georgia, Martin and Pelton might have been able to question the students whose admissions had implicated the whole group, and the council would not have been allowed to rely on evidence presented in hearings held when Martin and Pelton weren’t present, Tafelski said.

If Pelton had legal counsel at his hearing, his lawyer would likely have objected to the question about past marijuana use, stopping him from answering, Tafelski said. “We would have demanded that the school prove its case, which means holding them to the rules that he was accused of violating,” instead of upbraiding him for skipping class and smoking weed in the past.

The council ultimately stopped short of expelling Pelton and Martin but ordered them to finish high school at the district’s alternative school, a small building surrounded by barbed wire.

Their only recourse was to plead with the school board, which eventually agreed to let them return to class after they submitted more negative drug tests. But by then, they had missed three months of school and the basketball season. The college scouts disappeared.

Both students earned their diplomas, but neither has gone to college. They’re currently working as delivery drivers.

“It just ruined him,” Shatarra Pelton said of her son, now 21. The formerly outgoing jock “stopped talking, stopped hanging out. He spiraled.”

Pelton and Martin’s lawsuit against the district ended with an agreement to clear their records.

Pike County Schools Superintendent Mark Bazzell said that he can’t discuss matters related to specific students but wrote in an email that the district relies on an impartial tribunal to consider the facts in suspension and expulsion cases.

Bazzell has chaired many such panels, he wrote: “I always felt our administrators reviewed cases in a thoughtful manner and did their very best to balance the rights of students and the factual evidence in a way that would lead to a disposition that would result in the likelihood that the offense would not reoccur while also considering the need for the District to maintain good order and discipline in its schools.”

Both Pelton and Martin declined to be interviewed, saying they wanted to move on, but they gave their mothers permission to share their stories.

“It changed him,” Tasha Martin said of her son. “If he sees some kids that he went to school with on the internet, playing football, he’s like, ‘That could have been me. I was going to do this. They took it away from me.’”

‘A last resort’

State legislatures have been grappling with student punishment since at least 1994, when Congress passed the Gun-Free Schools Act, kicking off the zero-tolerance era by mandating expulsions for students with guns. That led to harsh laws across the country, punishing students for fighting, drugs and harder-to-define offenses like defiance.

Some states and districts began to soften those policies in the past decade, especially after the Obama administration flagged them as discriminatory and harmful.

But this year, as schools reported a spike in behavioral issues in the wake of the pandemic, states with both Democratic and Republican governors have taken steps to crack down. Kentucky made it easier to remove chronically disruptive students. West Virginia gave teachers more power to exclude disobedient children, while Nevada made it easier to expel students as young as kindergarten.

The hard-line approach on student punishment isn’t universal. Colorado enacted a student rights law this year that requires districts to give students the evidence against them two days before their hearing and to provide training for hearing examiners to ensure they understand concepts such as bias in student punishment, and the fact that children’s brains aren’t fully developed.

Other states have considered such legislation. In Alabama, the bill debated this year aimed to give students the right to see evidence at least five days before a hearing, to bring their lawyer, and to question witnesses. Opponents raised concerns that it would create new problems, such as the fear of retaliation for students made to testify against their classmates.

In Michigan, lawmakers introduced a package of student rights bills two years ago that would have required schools to hold impartial hearings within 10 days of removing a student and would have created an appeals process so students could contest punishments without having to sue. The bills never got a hearing.

A spokesman for the state Education Department, which did not take a position on the bills, said Michigan students already have due process rights. When asked about protections such as the right to legal representation and the right to see evidence before a hearing, he wrote in an email that those rights are “inculcated in state law and interpreted by the courts,” even if they’re not spelled out in statute.

But legal experts say that not having this language in state or federal statute makes students’ rights open to interpretation by schools, lawyers and judges.

“That leads to incredible inconsistencies and uncertainties,” said Derek Black, a Constitutional law professor at the University of South Carolina.

Republicans controlled both of Michigan’s legislative chambers in 2021 when the student rights legislation stalled. One of the sponsors, state Sen. Jeff Irwin, a Democrat from Ann Arbor, has higher hopes now that his party has more power. He plans to reintroduce the legislation this year.

“We need to make sure that school discipline is just,” he said. “The kids who get pushed out of school are often the kids who it’s most important that we equip with the skills to be successful in the workplace and be successful in life.”

Reporting for this article was supported, in part, by the Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship at Columbia University.