The first time I saw Jimmy Breslin, I barely got a glimpse. That’s because pretty much everyone else in my working-class Brooklyn neighborhood, circa 1976, already had surrounded him. It was like the pope had come to town, only with a lot more hooting, hollering and words that wouldn’t fly at the Vatican.

Breslin descended upon us after the back doors of an armored truck flew open and sent bags full of bills spilling onto Eighth Avenue, the main drag of Sunset Park. But we had to work for our paper riches: The cash, newly out of circulation, had been shredded beyond repair and blew about the street like spaghetti-clump tumbleweeds.

That didn’t stop my fellow 10-year-olds and me — and folks a lot older — from scooping up the U.S.-minted confetti by the armful and trying, in vain, to piece together a fortune or at least some pocket money.

When Breslin — the craggy face atop the column in the Daily News, the gravelly self-appointed voice of New York and future Son of Sam pen pal — arrived, we knew it was our lucky day. We were at the center of a story, an urban fairy tale that would have everyone talking.

For long after, I found myself telling to anyone who would listen the story of the time the streets became paved in green-tinted fool’s gold and brought Breslin to Sunset Park.

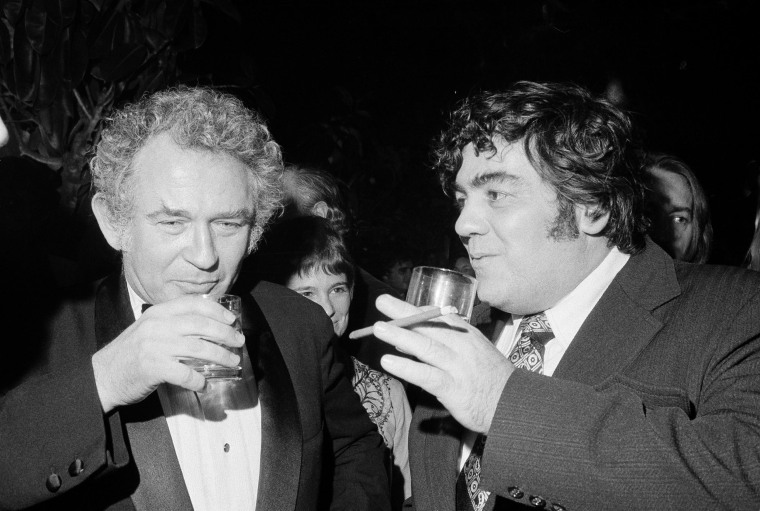

About a dozen years later, I was working at my first journalism job, as a reporter for a small Lower Manhattan paper, then called the Battery News. Breslin had just done the unthinkable: He quit the Daily News, where he’d infuriated gangsters, politicians (including "Society Carey") and other New York characters with his blunt, often caustic — and impeccably reported — columns. Along the way, he collected a Pulitzer, which was far less prestigious to his working-stiff readers than his commercials for Piels ("It’s a good drinking beer") and his 1986 "Saturday Night Live" hosting stint.

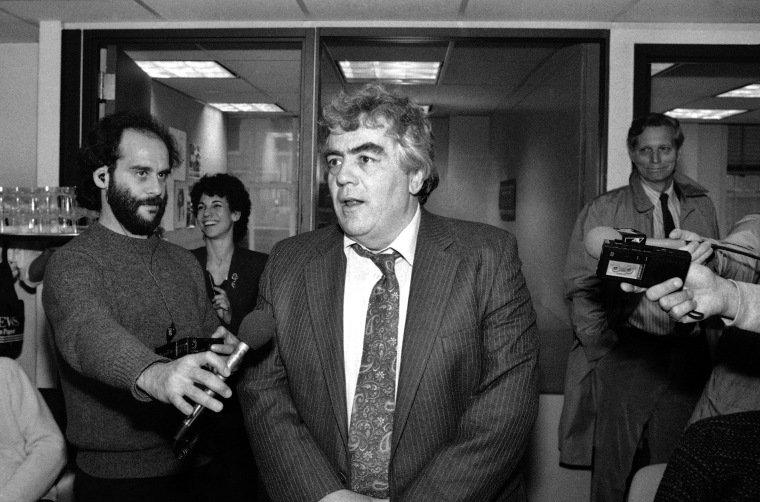

Breslin was headed to Newsday, the venerable Long Island paper whose growing New York City edition packed in quality what it lacked in flash — and circulation. Stealing Breslin was viewed as a potential game changer. One problem: Because of contract issues, it would be a while before Breslin would be able to write for Newsday.

My boss, John Cotter, a former Newsday editor, assigned me to interview Breslin. “Find out what he’s up to — ask him what he’d be writing about now if he had the column,” said Cotter, who gave me Breslin’s private number.

Related: Jimmy Breslin, Famed New York Columnist and Novelist, Dies

The prospect terrified me — I was daunted by the figure who dominated the Daily News, the paper my father brought home from work every night after delivering the U.S. mail, the only paper I ever wanted to work for. I’d also heard Breslin could be outright nasty to other journalists. I could write a bit, and was making strides in surmounting shyness to become a reasonably aggressive reporter. But I trembled at the notion of cold-calling Breslin.

I invented an excuse to leave the office, and spent hours walking the streets of Manhattan, trying to steel my resolve. I thought about quitting. This was make or break.

I called Breslin — three times. We had three brief conversations, all of which consisted of him berating me for bothering him, giving me a great quote or two about how his feuding partner Ed Koch was destroying the city and telling me to go f--k myself before hanging up.

I cobbled together enough for an item for the paper. Cotter was pleased. So was I — I felt like I had passed a test.

I didn’t find out until a few weeks later the real exam I’d aced. Breslin was looking for an assistant. The kid who stammered his way through three crazy-but-normal-for-Breslin phone calls would do.

But Cotter vetoed the gig, without telling me about the opportunity until after the fact: "I thought he needed someone to run quotes for him, but Breslin still does all his own legwork. All you would do would be getting him his cigars. You’re beyond that. You need to keep reporting."

I was crushed. But I took it as a sign I was on the right track.

Months later, as Christmas neared, Breslin’s wife, Ronnie Eldridge, then a City Councilmember, dragged him to the holiday party at our newsroom, which housed three Manhattan community papers in a dank former hat factory on the border of then decidedly untrendy Chelsea. She was as outgoing as he was sullen. Still, Breslin drew the bigger crowd.

Related: Jimmy Breslin, the Gravedigger and 'the Bleary Day' They Buried JFK

This time, I managed to edge my way close to the Queens-born tabloid poet laureate. He was encouraging a reporter working on a story about local Filipinos to make a long distance call. "Pick up the phone and demand to speak to (then-Philippines President) Corazon Aquino!" he thundered. "Remember: 'Luck is the residue of design.'"

Out of pure reflex, I spouted, “Branch Rickey!” I knew the quote and its source: Rickey was the Brooklyn Dodgers executive who recruited Jackie Robinson to break baseball’s insidious color line four decades earlier.

Breslin turned to me and recounted, in his own terms, perhaps the greatest New York story of them all.

"Rickey and Robinson did more to help the cause of racial equality in this country than anybody — and don’t let anyone tell you anything different," he said.

He shook his fist chest-high, as if celebrating a victory, and smiled.

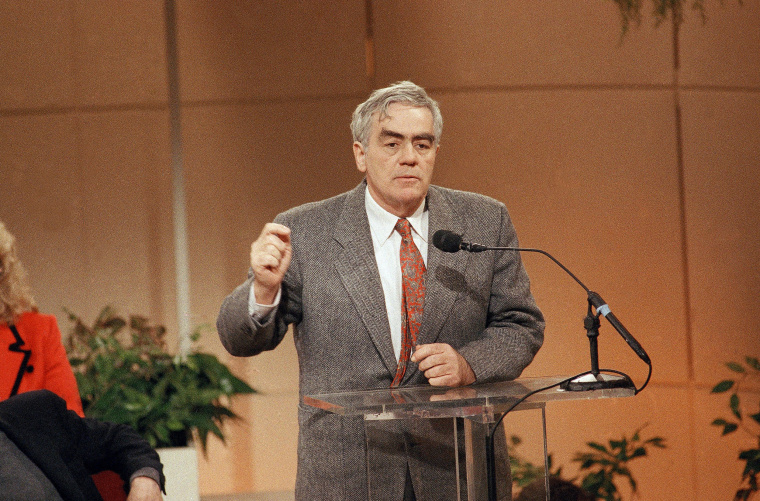

Breslin’s short book about Rickey and Robinson came out in 2011. The great New York investigative reporter Tom Robbins convinced him to speak at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, where I now work. The J-School occupies the old headquarters of the New York Herald Tribune, the long-defunct paper for which Breslin wrote his classic column about JFK’s gravedigger, the kind of piece they teach about in journalism schools.

Breslin, by then 82, rambled occasionally, but quickly snapped back to retell the Rickey-Robinson story, much as he had done for me more than two decades earlier.

Afterward, I got in line to get my copy of the book signed. When I reached Breslin, I spelled my unusual first name for him.

He stopped writing and looked up as if he knew me. Maybe he was being polite, or maybe he recognized the name from the byline that topped more than 1,500 Daily News stories in the 1990s.

"How you doin’? What are you up to?" he asked, as if I were a long-lost pal. I told him I was working at the J-School, helping to train young reporters.

"And you know what I always tell ‘em, Jimmy?" I said, unconsciously lapsing into the boyhood Brooklyn accent that only emerges when I’m with family or friends from the old neighborhood.

"Luck is the residue of design."

With that, Breslin gave a little fist shake and smiled.

Jere Hester is Director of News Products and Projects at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism. He is also the author of "Raising a Beatle Baby: How John, Paul, George and Ringo Helped us Come Together as a Family." Follow him on Twitter.