High-speed video cameras are allowing university researchers to document how butterflies gracefully flutter through the air. The U.S. military funded findings may lead to more agile insect-sized drones sent to spy on enemies.

A key finding is that butterflies appear to use their bodies and wings to twist and turn in the air in a way similar to how ice skaters use their arms to control the speed of their spins, explains Johns Hopkins University undergraduate Tiras Lin, who is working on the high-speed video research.

"Ice skaters who want to spin faster bring their arms in close to their bodies and extend their arms out when they want to slow down," he explains in the video news release below.

"These positions change the spatial distribution of a skater's mass and modify their moment of inertia; this in turn affects the rotation of the skater's body. An insect may be able to do the same thing."

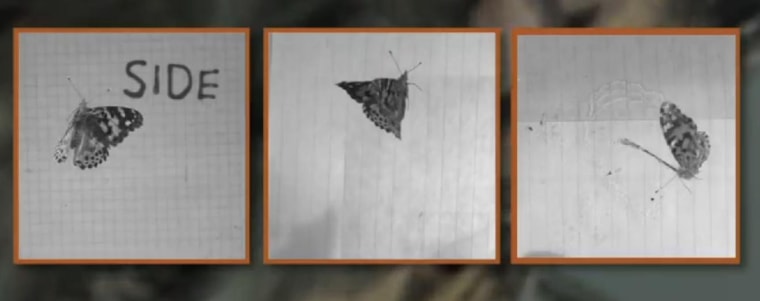

To capture the images of butterflies in flight, Lin used video cameras that record 3,000 one-megapixel images per second. To put that in perspective, a standard video camera shoots 24, 30 or 60 frames per second. "Butterflies flap their wings about 25 times per second," Lin notes.

Most of his analysis zeroed in on 1/5th of a second of flight, or about 600 frames.

Lin recently presented his findings at a meeting of the American Physical Society's Division of Fluid Dynamics. While they haven't yet been adopted by next-generation drones, he said they ought to be. To see how else drones could get buggier in the future, check out the stories below.

More stories on insect-inspired drone technology:

- Biofuel cells may turn cockroaches into cyborgs

- Military developing robot-insect cyborgs

- On wings of technology: Humming bird drones

- Ant-like robots poised to invade the marketplace

John Roach is a contributing writer for msnbc.com. To learn more about him, check out his website. For more of our Future of Technology series, watch the featured video below.