For many Americans, the idea of divided government -- one branch led by one party, one branch led by another -- has a certain appeal. The division can serve as a kind of check against partisan excesses, at least in theory, while forcing policymakers to strike compromises.

But that was before the 112th Congress changed public attitudes.

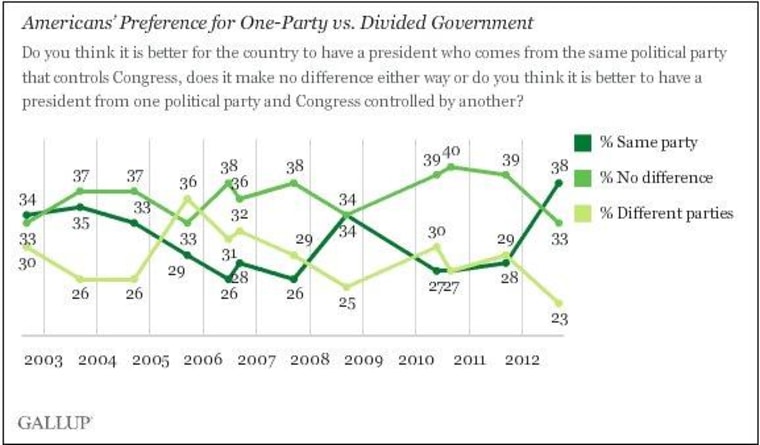

Gallup ran this report yesterday noting the spike in the number of Americans how believe it's better to have the same party control both the White House and Congress. It's reached a record high, and it's the first time in a decade that this is a plurality view.

There's no great mystery here. Congressional Republicans, after creating a debt-ceiling crisis, multiple government-showdown crises, and making even routine governing nearly impossible, have offered a brilliant civics lesson on the dangers of divided government.

For what it's worth, the idealized notion of divided institutions finding common ground to advance public interests isn't ridiculous on its face, but it's dependent on having two mainstream political parties, sincere in their commitment to governing. When one abandons institutional norms and becomes radicalized, divided government doesn't lead to more compromise, it leads to less.

And as the Mann-Orstein thesis tells us, "When one party moves this far from the mainstream, it makes it nearly impossible for the political system to deal constructively with the country's challenges.... The GOP has become an insurgent outlier in American politics. It is ideologically extreme; scornful of compromise; unmoved by conventional understanding of facts, evidence and science; and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition."

Gallup's report on the results also raised an interesting point to keep an eye on: "As the 2012 election approaches, these findings suggest that Americans may be somewhat less open to ballot splitting than in prior years."