The presidential campaign has been consumed in recent weeks by a series of manufactured political battles over motherhood. These conflicts, however, obscure the realities of what it actually means to be a mother in modern America, and how much — or how little — the government is willing to do to help parents across socioeconomic classes succeed in raising their children. In this respect, the United States diverges sharply from virtually the rest of the industrialized world.

For our show on motherhood on Sunday, we worked up a few charts which, we think, paint an especially striking portrait of the state of modern motherhood in America. In short: compared to the rest of the industrialized world, America isn’t nearly as hospitable a place for mothers as we like to think.

On Mother’s Day we exalt the cultural status of motherhood, and rightfully so. But as these figures suggest, our praise for mothers is so often mere lip service. What we actually do from a policy standpoint to make mothers’ lives easier is, in many cases, meager compared to the rest of the world.

For example, according to the annual “State of the World’s Mothers” report from the Save the Children organization, the U.S. ranks as the 25th best country in the world to be a mother.

You’ll notice that the top of the list is dominated by European and other industrialized nations with strong social welfare states, which in many cases provide a robust safety net for mothers including universal daycare and paid family leave.

America’s low ranking is especially shocking given the size of our economy, which, of course, vastly outstrips those of countries like Brazil and the Czech Republic.

America’s ranking on access to daycare is especially poor. There are 33 countries — including Malta, of all places — that provide better access to daycare for children. In France, for example, 99 percent of children aged three to six are enrolled in daycare. In the U.S., that number is about half.

Daycare isn’t just inaccessible to many Americans — it’s also unaffordable. According to data from the National Association of Childcare Resource and Referral Agencies, the annual cost of daycare for infants is more expensive than tuition for public colleges in 40 states. In New York, the cost of daycare is more than double the cost of public college tuition and fees.

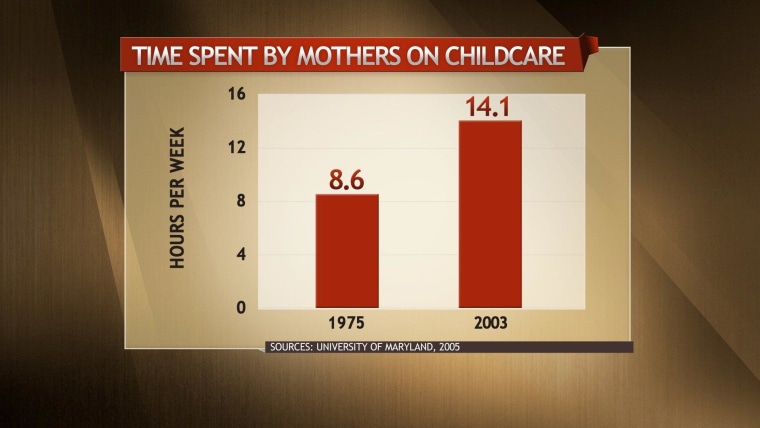

And here’s an especially startling statistic: Because so many Americans lack access to basic childcare, mothers are actually spending considerably more time caring for their children now than they were in 1975, at the height of the feminist movement. Fathers, meanwhile, are spending roughly the same amount of time on chores and housework as they were 20 years ago, according to a 2005 study by sociologists at the University of Maryland.

The lack of supportive government policies like paid family leave might also explain, in part, the vast gulf between the numbers of high-income and low-income mothers who breastfeed their children. Among mothers at 185 percent of the poverty line or lower — the level at which a family qualifies for federal nutritional assistance — only 57 percent of women breastfeed their children. By contrast, nearly three-fourths of wealthier mothers breastfeed. Many of those mothers, of course, can afford to stay at home and care for their children if they so choose. Mothers who must work to support their families, however, often find it harder to carve out time during the day to breastfeed.

The social and political status of women has changed considerably since the genesis of the Second Wave feminist movement in the 1960s — and yet our policies have remained essentially the same. Today, nearly 60 percent of mothers with children under the age of one are in the workforce. And yet, mothers are spending even more time on childcare than they did 50 years ago. Somehow, they manage it — which is, in itself, a feat to be admired and marveled at on Mother’s Day. But perhaps we should also consider the ways in which those cultural changes should impact our policies, too.

When he was running for Senate in Massachusetts in 1994, Mitt Romney took roughly this same position. The case he made then for accessible childcare is striking not only in its divergence from Republican orthodoxy, but in its appreciation for the increasingly difficult expectations modern mothers face.

“This is a different world than it was in the 1960s when I was growing up, when you used to be able to have mom at home and dad at work. Now mom and dad both have to work whether they want to or not, and usually one of them has two jobs,” Romney said during a Senatorial debate in October of 1994. “And if that's the case, we're going to have to have good childcare in the community.”

Sal Gentile is a segment producer for "Up w/ Chris Hayes."