The ’90s are back — at least, they are in Hollywood.

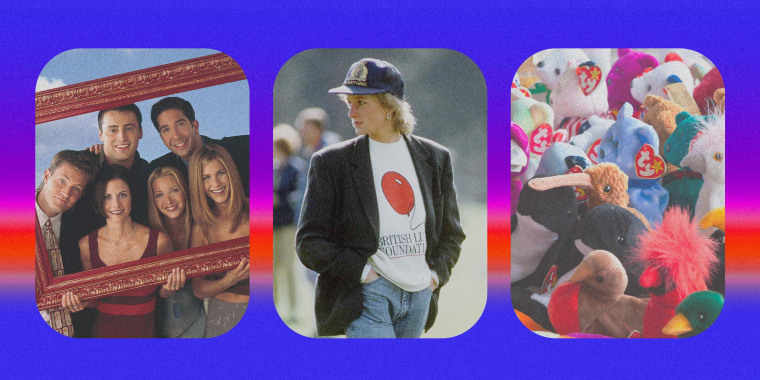

Movies, shows and podcasts are once again being made about Princess Diana. HBO Max debuted a "Friends" reunion, called "The One Where They Get Back Together," which was a huge hit in May. Netflix released the second season of "The Baby-Sitters Club" reboot, and Peacock released the second season of its "Saved By the Bell" reboot. More recently, HBO Max released a reboot of "Sex and the City" called "And Just Like That..." and a documentary about Beanie Babies.

Those are just some of the many ’90s-centric pop culture offerings from Hollywood this year. There's still more to come, including a Netflix spinoff of hit sitcom “That ‘70s Show” called — you guessed it — “That ’90s Show.”

Resuscitating old Hollywood material isn’t anything new, according to some pop culture experts. But the resurgence of ’90s fodder feels particularly pronounced in another trying year defined by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Experts say people can get nostalgic for a period of time as early as 15 years after that period that occurred, and as late as 40 years after, essentially covering a life cycle that begins when some parents come of age and ends when their children are doing the same. That allows for the reintroduction of recycled content to younger audience members and drawing in older viewers enticed by feelings of nostalgia.

And if these iconic shows and movies worked once, why wouldn’t they work again?

“This phenomenon offers an opportunity to recycle stories and characters that appealed both to the parents when they were younger and to their children, or the current generation just coming of age,” said Susan Mackey-Kallis, a communications professor at Villanova University who studies pop culture and film analysis.

Raj Mayadunne, 31, said he loves having his beloved ’90s favorites back in the zeitgeist.

"It's like Princess Diana and Carrie [Bradshaw] grew up with me," Mayadunne said. "It reminds me of a happier, more innocent time, when I had fewer worries and responsibilities. No student loans."

Nostalgia is a powerful emotion that “feels oddly comforting to go back to” because the memories people associate with childhood entertainment often “shape our worldviews,” said Yalda T. Uhls, an assistant adjunct professor of psychology at UCLA who spent 15 years as senior film executive.

It makes sense, Mackey-Kallis added, given that the word for nostalgia derives from the Greek words “nostos-” (home) and “-algia” (pain).

“A home pain or homesickness — an aching to return to a time and place for which one has happier associations,” Mackey-Kallis said.

I don't think it necessarily matters if I physically wasn't on this planet during the 1990s. That archive exists for people like me to discover it anew.

Kelly Tan, 21

She noted, however, that for some people, experiences so intense can sometimes collapse the actual reality they refer to. By extension, those moments “captured in media representations like popular remakes” likely “never existed,” she said.

The false wistfulness of the ’90s rings especially true for Gen Z kids who were born in the 2000s.

Kelly Tan, 21, said it didn't matter whether she was alive during that decade.

"I don't think it necessarily matters if I physically wasn't on this planet during the 1990s," she said. "That archive exists for people like me to discover it anew."

She added: "I'm obviously not a royal member of the British family nor did I even exist when Diana was alive, but it's just fun to pretend like I did grow up around then, as if it did happen, you know?"

The explosive return to the past isn’t just limited to entertainment, either. Earlier this summer, iconic fashion trends of the early 2000s — like bucket hats, low-rise jeans and babydoll T-shirts — made a comeback among younger consumers. Y2K clothing, or what has been called “nowstalgia,” became an attempt to relive early 2000s fashion trends that Gen Z people were too young to experience or remember the first time around.

Regardless of the medium, longing for a time when things felt simpler and easier is heightened in a moment of incalculable loss and grief, according to experts. In December, the United States passed another Covid-19 milestone as the number of Americans who have died from the virus surpassed 800,000.

“There’s been a lot of pain with the pandemic,” Mackey-Kallis said. “How do we retreat from the pain? We go home; we go back to the past that’s nostalgically ‘better.’”

Film and television studios also have a financial incentive to revive favorite shows and characters of the past, experts said.

“Studios are afraid to take a risk on new content, so they rely on existing IP, in hopes that if the story worked once, it will work again,” Uhls said, referring to intellectual property.

That hope, Mackey-Kallis said, would ideally translate to high box office numbers and viewership, or in the case of streaming services, new subscribers — both of which contribute to companies generating more revenue.

How do we retreat from the pain? We go home; we go back to the past that’s nostalgically ‘better.’

Susan Mackey-Kallis, Villanova University COMMUNICATIONS PROFESSOR

Of course, that isn't always the outcome.

For example, “Ghostbusters: Afterlife,” which debuted in November, drew large crowds to theaters. But some critics were still lukewarm on the return of such a beloved franchise, which originated in 1984.

The film "instinctively understands that nostalgia is popular culture’s most valuable commodity right now," writer Jack King noted in a piece for BBC, titled "Ghostbusters Afterlife: Is nostalgia killing cinema?"

"If it’s easy to criticise the studios’ appeal to nostalgia as cynical, then it’s clear, from the box-office results, that it’s hitting the spot — and really is there anything ignoble about fans’ desire to be reminded of the things they love?" King wrote. "The problem is, however: where does the nostalgia obsession end?"

Still, some experts say reusing old content can continue to be successful, as viewers will likely consume these offerings at near-immediacy.

“The pandemic has certainly intensified our pain and our desire to return to the past, to feel safe from things that are painful,” Mackey-Kallis said. “Even if that reality may have never existed, what would be better than to watch content that reminds you of a time before the pandemic?”