Ice cold beer: In these dog days of summer, few things are better. So, let's raise a glass and toast Saccharomyces eubayanus, newly discovered yeast that helped make cold-fermented lager a runaway success.

The yeast, in the wild, thrives in ball-shaped lumps of sugar that form on beech trees in Patagonia of South America. Its discovery appears to solve the mystery of how lager yeast formed. Until now, scientists only knew about the origins of ale yeast, which makes up just half of the lager yeast genome.

Yeasts are microscopic fungi that feast on sugar, converting it to carbon dioxide and alcohol via the process of fermentation. Ale yeast, S. cerevisiae, has been doing this throughout the history of beer, which stretches back to at least 6,000 B.C. in Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization.

But ale yeast does its magic at relatively warm temperatures. In the 15th century, Bavarians started cold-fermenting beer in caves, a process known as laagering.

"The ale strains were probably poorly adapted to growing in that environment and that opened up an opportunity when S. eubayanus came on the scene," Chris Todd Hittinger, a professor of genetics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, explained to me.

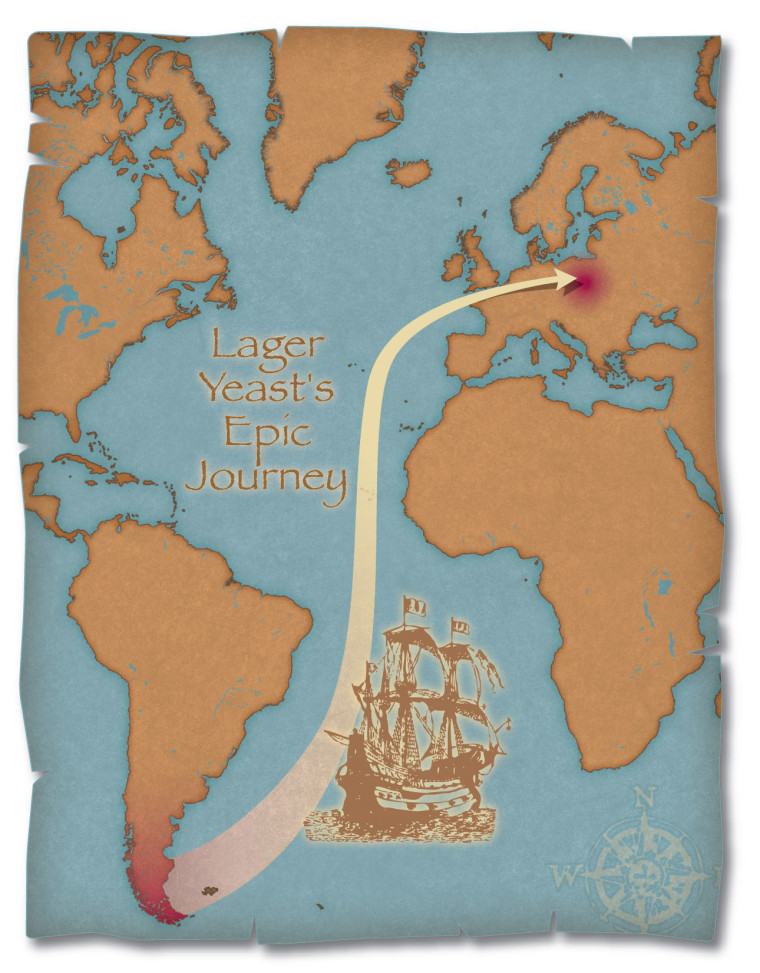

The cold-adapted yeast likely reached Europe as stowaway when trade with South America took off in the 1500s, he and colleagues report online today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Once in Europe, the Patagonia yeast fused with S. cerevisiae. "By forming a hybrid, you get an immediate temperature shift in its preference and that would have provided an immediate advantage to the process the Bavarians were using to make beer," Hittinger said.

He and his colleagues used genetic sequencing techniques on a search of five continents for this wild yeast species. Their quest was to complete the puzzle in part so that genetic engineers and brewers can create ever-more efficient strains of lager yeast and, potentially, a better beer.

That, in turn, could be a boost in the highly-competitive brewing industry. Lager, according to the researchers, is a $250 billion a year business.

Credit for the discovery of this wild yeast goes to Diego Libkind of the Institute for Biodiversity and Environment Research in Bariloche, Argentina, who was interested in the ball-shaped lumps of sugar that form on beech trees there.

The lumps, called galls, are an immune response to invasion by a fungus. They are abundant in the spring and local Aborigines such as the Mapuche traditionally use them as a slightly-sweet topping for salads, Libkind explained to me in an email.

In addition, "the Aboriginies used to let the galls spontaneously ferment in water and made an alcoholic beverage called by the generic name chicha," he said. "Most probably, S. eubayanus was in charge of that fermentation."

Today, Libkind and his colleagues are working with a microbrewery in Argentina to diversify their products with S. eubayanus and "artificially forced S. eubayanus/S. cerevisiae hybrids," he said.

Details on these products are under wraps, he said, though since yeast go under thousands of years of domestication by brewers, he doubts the wild yeast would make for a good beer.

But the idea of brewing a beer with S. eubayanus might be worth pursuing, Hittinger said. "It would unlikely be a particularly great beer straight out of the beech forest, but I suspect it would be passable."

Update, Aug. 23, 2:00 pm PT:

Patrick McGovern, a world expert on the history of alcoholic beverages and director of the biomolecular archaeology lab at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, sent me an email today with his thoughts on the yeast discovery.

Assuming the genetics work is correct, he said he is "troubled by how this newly discovered wild yeast strain made it into Bavaria in the 1500s."

For one, he noted, Germans, and especially Bavarians, were not involved in the European exploration of Patagonia at the time. So, if the yeast somehow hitched a ride back to Europe via trade with the English, Spanish, and Portuguese, how did it get to Bavaria?

"Perhaps, some Patagonian beech was used to make a wine barrel that was then transported to Bavaria and subsequently inoculated a batch of beer there?" he asked. "Seems unlikely."

He said a more likely scenario is that galls in the oak forests of southern Germany also harbored S. eubayanus, at least until it was out competed by the more ubiquitous S. cerevisiae.

"If true, then the use of European oak in making beer barrels and especially processing vats, which could harbor the yeast, might better explain the Bavarian 'discovery' of lager in the 1500s," he said.

Nevertheless, he added, history and archaeology are full of surprises.

"Nowhere is this more true than of the seemingly miraculous process of fermentation and the key role of alcohol in human culture and life itself on this planet," he said.

"This article has begun to unravel the complicated heritage and life history of the fermentation yeasts, and will hopefully stimulate more research to see whether the Patagonian hypothesis proves correct."

More stories about beer:

- Happy (hic) birthday, canned beer!

- Ancient Nubians drank beer laced with antibiotics

- Beer may have lubricated rise of civilization

- Tip a glass to these Iron Age beer makers

- In ancient Peru, women made the beer

- Ancient yeast reborn in modern beer

John Roach is a contributing writer for msnbc.com.