Genes from 5,000 years ago show that the Europeans of that crucial historical era were predominantly light-skinned — and mostly lactose-intolerant.

The findings, based on a rough analysis of genetic material extracted from the teeth of 101 ancient humans, provide snapshots of how mass migrations changed Europe's peoples during the Bronze Age, which lasted from around the year 3000 B.C. to 1000 B.C.

That era marked the transition from a predominantly hunter-gatherer way of life to a predominantly agricultural lifestyle, and the rise of urban civilizations ranging from Babylon to pharaonic Egypt to classical Greece and Rome.

The scientists behind the genetic survey, described in this week's issue of the journal Nature, wanted to find out how large a role migrations played in the cultural ferment. The results suggest they played a huge role.

"We show that the Bronze Age was a highly dynamic period involving large-scale population migrations and replacements, responsible for shaping major parts of present-day demographic structure in both Europe and Asia," they reported.

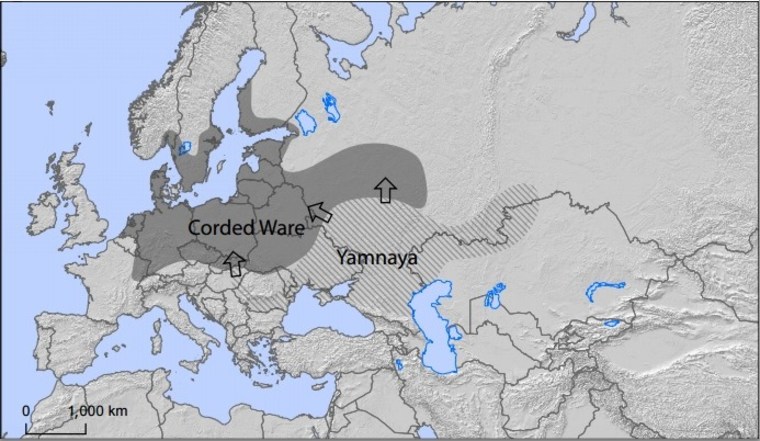

Their analysis indicates that the era's most significant migration was the rapid expansion of a culture known as the Yamnaya, which pushed out from the steppes of the Caucasus and Ural regions into northern Europe in the early Bronze Age. The patterns of genetic signatures suggest that the Yamnaya interbred with the hunter-gatherers and farmers already living in northern Europe — influencing the development of another ancient set of peoples called the Corded Ware culture.

A closer analysis of some key genes hinted at what Bronze Age Europeans looked like, and how they lived. The researchers found widespread distribution of a gene that's linked to light skin, and medium distribution for a gene associated with blue eyes.

Related: Genes Paint 7,000-Year-Old European's Picture

Surprisingly, only about 10 percent of the European samples showed evidence of a gene that's associated with lactose tolerance. Previous research suggested that the ability to digest milk should have been much more widely distributed in Europe by 3000 B.C.

In 2009, one study laid out a hypothesis claiming that lactose tolerance spread out from the region around modern-day Hungary starting 7,500 years ago.

"Given these results, I would argue it to be extremely unlikely for this hypothesis to hold," said Martin Sikora, an author of the Nature paper who is based at the Center for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen's Natural History Museum. "If it was present in Hungary that early, it would have to be at extremely low frequencies."

Related: Europeans Made Cheese 7,500 Years Ago

Other findings touched on a different controversy surrounding the Bronze Age, having to do with the rise of Indo-European languages — the ancient tongues that evolved into modern languages ranging from English to German to French to Russian to Hindi. The researchers said their results were consistent with a scenario for the spread of Indo-European languages from the Yamnaya steppes during the early Bronze Age.

"I think the main caveat to those results is that ... our evidence for migration does not prove that the Yamnaya actually brought the Indo-European language with them," Sikora told NBC News in an email. "We obviously can't know that from the genetic data."

Paul Heggarty, a linguistics researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, agreed that the genetic evidence doesn't resolve the questions about the spread of language. He favors a different scenario — in which the Proto-Indo-European language spread out from what is now Turkey, thousands of years before the Bronze Age began.

"The new genetic data are just as compatible — if not more so — with the steppe expansions as a secondary phase, after most of the rest of the language family had spread earlier with farming," Heggarty told NBC News. He said still more genetic data would be needed to resolve the issue.

Related: Danish Bronze Age Woman Was From Somewhere Else

It took a combination of innovations to conduct the Bronze Age analysis: The researchers started out with more than 600 samples that were taken from the top layers of ancient teeth, and then put through a "pre-digestion" chemical treatment that's designed to remove surface contamination. They also used a new kind of DNA extraction treatment that was developed specifically for the extraction of ancient DNA. After all that, they ended up with 101 samples that were solid enough to analyze.

"Our study is the first to apply these recent methods on that large of a scale, so it will provide the basis for many future studies to unravel some of the more detailed questions," Sikora said. "We have really only scratched the surface of what can be done with these data."

For more from Paul Heggarty about ancient DNA analysis and what it means for the Indo-European language issue, check out his blog posting at Diversity Linguistics Comment. A related research paper, titled "Massive Migration From the Steppe Was a Source for Indo-European Languages in Europe," was published online by Nature in March and appears in this week's print version of the journal. Nature's Ewen Calloway discussed the issue in depth in an article published in February. Science's Michael Balter passes along an audio file that lets you hear what Proto-Indo-European sounds like.