An exhaustive survey of decades-old spy satellite pictures has turned up thousands of previously unknown archaeological sites — including the vestiges of lost cities.

The revelations come from the CORONA Atlas of the Middle East, a database of annotated Cold War imagery that received its formal unveiling last week at the Society for American Archaeology's annual meeting in Austin, Texas.

"The thing that's most exciting about this is the bigger picture that we're getting from mapping the region," University of Arkansas archaeologist Jesse Casana, a co-director of the project, told NBC News. "Within our study area in the Northern Fertile Crescent, we've documented 15,000 sites, and only a third of those have previously ever been even rudimentarily documented. Only a tiny number have been excavated."

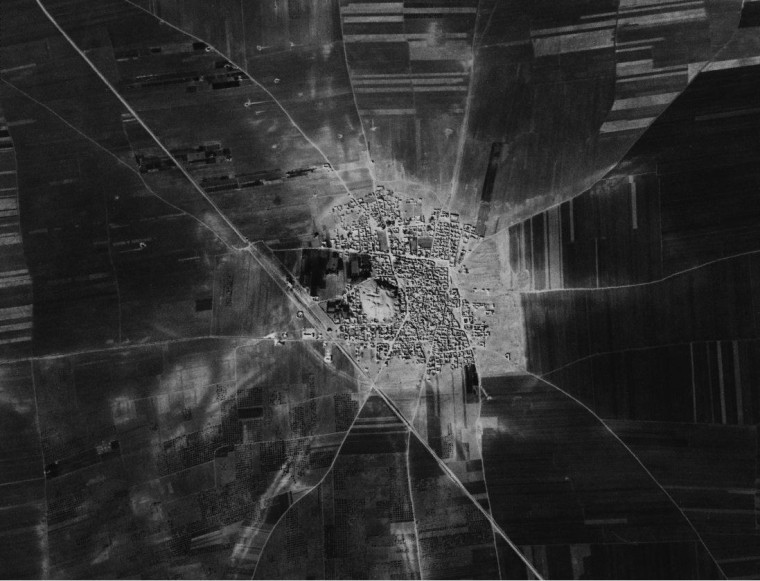

The black-and-white images, spanning areas that stretch from Egypt to Iran, were captured by the United States' CORONA spy satellite in the 1960s and early 1970s, and declassified in 1995.

Casana and his colleagues at the University of Arkansas' Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies have been rectifying the raw CORONA images and checking them for the telltale signs of bygone settlements.

Today's satellites provide higher-resolution, full-color views of the same areas, but the CORONA imagery comes from a time when the Middle East's ancient sites were less disturbed by modern development. "It preserves the picture of a landscape that in many cases no longer exists," Casana said.

One of the CORONA pictures reveals the circular outline of a 370-acre (120-hectare) fortified city at Tell Rifaat in Syria. That outline "was never documented by archaeologists, and now is covered by the modern city," Casana said. Another picture shows what appears to be a previously undocumented 125-acre (50-hectare) city in south-central Turkey. That settlement probably dates back to the Bronze Age, more than 3,000 years ago.

Many of the newly recognized sites may well get a closer look, but the CORONA Atlas also shows how ancient settlements were distributed on a large scale, even in places where archaeologists can't go. "We can map the extent of settlements outside survey boundaries and across national boundaries," Casana said.

The CORONA Atlas Project's other co-director is Jackson Cothren. Tip o' the Log to National Geographic's Dan Vergano.