Richard Nixon made his first Meet the Press appearance on September 14, 1952, less than two months before the presidential election in which he was standing as General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s running mate. Nine days later, he was back in front of the television cameras, to deliver the “Checkers” speech denying campaign finance irregularities. The highlight of the speech was his refusal to give up one special gift—the black-and-white dog his children had named “Checkers.”

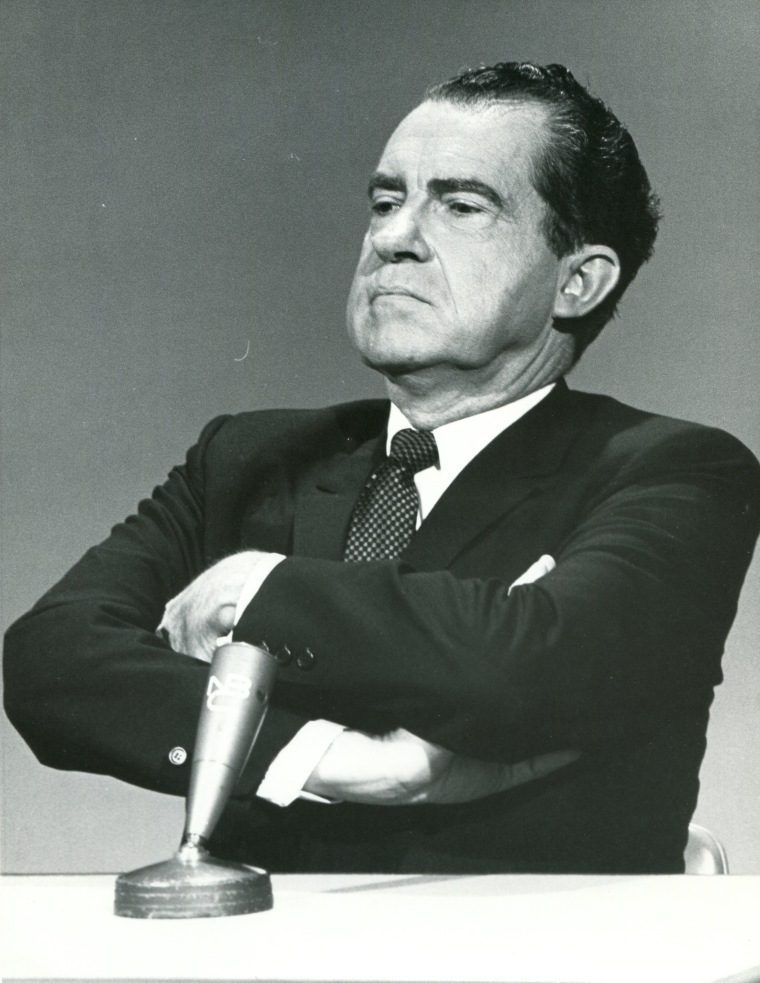

The Checkers speech was considered a triumph—Eisenhower and Nixon won in a landslide—but Nixon was never comfortable with his TV persona. In April 1988, when Meet the Press moderator Chris Wallace showed him a clip from the 1952 program, he said: “That’s one of the first times I’ve ever seen myself on television. As I was telling you before the show began, I simply have a phobia about that.” It is widely believed that when Nixon faced the telegenic and confident John F. Kennedy in the first-ever televised presidential debates in 1960, his pale, perspiring performance contributed to his narrow defeat in November.

“I have great respect for those that put emphasis on charisma, which I'm not supposed to have,” he told Meet the Press on November 3, 1968, two days before his victory in the presidential election against Democrat Hubert Humphrey and American Independent Party candidate George Wallace, the former governor of Alabama. He added: “I think what is more important is to listen and do something—action, a program of action.”

Nixon had a difficult relationship with the media throughout his career. At a press conference following his defeat in the 1962 election for governor of California, he announced: “You don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore, because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.” He felt the press had been unfair to him: “They have a right and a responsibility—if they are against a candidate, give him the shaft, but also recognize if they give him the shaft, put one lonely reporter on the campaign who will report what the candidate says now and then.”

Before the 1962 election, Nixon had told Meet the Press about a greater threat to the United States than a biased press: Communism. “For every Communist in this state you must multiply his power a thousandfold by the fact that he is an agent of and is supported by the international Communist conspiracy, which is an enemy of the United States.”

Nixon had first come to national attention in 1948 as a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee investigating Alger Hiss, who had been identified as a Communist spy by Whittaker Chambers on Meet the Press in August 1948. Nixon fought Communism at home and, as president, overseas, but in 1972 he flew to Beijing and established relations with the People’s Republic of China, isolated from the West since the 1949 Chinese Revolution. With National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, he pursued a policy of détente with the Soviet Union; he held Strategic Arms Limitation Talks with the Soviet Union in 1969, and signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 1972.

Nixon won reelection in 1972 in an overwhelming landslide over Democrat George McGovern, losing only in Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. But it emerged that on June 17, 1972, five men had been caught breaking into the Democratic National Committee’s Washington offices in the Watergate complex. The press pursued the story, and the trail led to Nixon’s campaign and eventually to a White House cover-up. After a Senate enquiry and legal battles over the release of Nixon’s tapes of his Watergate conversations, the House of Representatives Judiciary Committee approved impeachment. On August 9, 1974, Richard Nixon resigned the presidency.

“Watergate was a breach of trust,” he said on Meet the Press in 1988. “In 1972 we went to China. We went to Russia. We ended the Vietnam War effectively by the end of that year. Those were the big things. And here was a small thing and we fouled it up beyond belief…And apart from the fact it was wrong, it was stupid. And generally, I’m called many things, but not often am I called stupid.” He had advice for future presidents: “Do the big things as well as you can, but when a small thing is there, deal with it, and deal with it fast. Get it out of the way, because if you don’t, it’s going to become big, and then it may destroy you.”

And his legacy? “We changed the world. If it had not been for the China initiative, which only I could do at that point, we would be in a terrible situation today, with China aligned with the Soviet Union and with the Soviet Union’s power.”