Virginia officials are investigating whether doctors tried, and failed, to find help for Austin "Gus" Deeds before he apparently stabbed his father, state Sen. Creigh Deeds, and shot himself in rural Virginia Tuesday.

Several sources say the younger Deeds, who was 24, was evaluated at a local hospital and sent home when doctors couldn’t find a place in a psychiatric facility. The Washington Post reported Wednesday that some nearby hospitals did have beds but were never contacted.

Mental health experts say it’s a longstanding issue and even though the Affordable Care Act makes insurers pay for mental health care, it’s unclear where people are going to get that care.

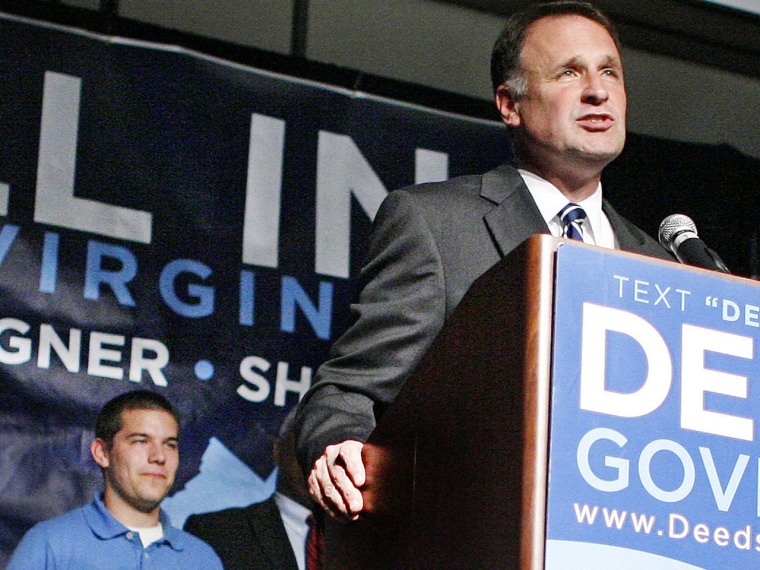

Creigh Deeds, 55, was listed in good condition at the University of Virginia medical center Wednesday after he was stabbed in the head and chest. Police say his son, Gus, killed himself using a rifle.

Such cases make for lurid headlines — young men suffering from mental health problems who have killed others. Adam Lanza, who killed 20 young children at a Connecticut school last December; Seung-Hui Cho, who killed 32 other people at Virginia Tech in 2007; Jared Lee Loughner, diagnosed as schizophrenic after he shot and killed six people in Arizona in 2011 and wounded 13 others, including former Rep. Gabby Giffords.

Experts say the mentally ill are not usually violent and say the police aren't the answer. And many times such an attack is the first sign of mental illness. But many times, health professionals do try to help.

Dennis Cropper, executive director of the Rockbridge Area Community Services, was quoted by local media as saying the younger Deeds had been held under an emergency custody order (ECO) while doctors at Bath Community Hospital looked for a place at a psychiatric hospital for him. He later issued a statement saying he wanted to respect the family’s privacy.

But he also detailed a system that gives doctors just four hours to find specialized treatment for people having an acute psychiatric crisis. “Within those four hours, if a mental health professional determines that they need a psychiatric bed space, they have to use those same four hours to locate a receiving facility,” Cropper said in the statement.

“In certain conditions a two-hour extension is granted by a magistrate, but under no circumstances can a person be held beyond six hours involuntarily under an ECO.” Bath Community Hospital released a statement Wednesday saying it is not equipped to provide mental health services.

This all paints a picture of doctors frantically searching for treatment and then releasing a patient in dire need of care. And that’s what is happening all over the country, says Doris Fuller, executive director of the Treatment Advocacy Center, which conducts research on mental health issues.

“We will keep seeing tragedies like this until we provide sufficient inpatient beds to meet the needs of people in psychiatric crisis,” Fuller said in a statement. “If there had been a hospital bed available for Gus Deeds, he may be alive today, and his father would not be grievously wounded.”

Virginia mental health officials have been battling a shortage of psychiatric beds there.

Rockbridge was designated a Mental Health Professional Shortage Area by the federal government’s Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). So was Bath County, where Deeds lived. That means there’s only one psychiatrist for every 30,000 people there. “Applying this formula, it would take approximately 2,400 additional psychiatrists to eliminate the current mental health professional shortage area designations,” HRSA says on its website.

The problem dates back to the 1960s and the birth of Medicaid, says Kristina Ragosta of the Treatment Advocacy Center. “One of the reasons there are so few state psychiatric beds and the reason states continue to shut hospital doors is that the federal government typically does not reimburse states for state psychiatric hospitals,” Ragosa said in a telephone interview. It’s called the Institutions for Mental Disease exclusion, and means Medicaid doesn’t pay for treating most patients at mental health facilities.

“While it remains unclear whether Gus Deeds suffered from a diagnosed mental illness, this tragedy appears to be yet another incident related to our failure as a nation to provide adequate treatment options for the most severely ill,” Fuller said. “Virginia only has 37 percent of the beds available necessary to meet the needs of its population,” she added, citing a recent study her group did.

“This continuous emptying of state psychiatric hospitals for the past half century has reduced the number of public beds for acutely or chronically ill patients by more than 90 percent while the U.S. population nearly doubled.”

The 2010 Affordable Care Act designates mental health as one of 10 essential services that health insurance must pay for. But Ragosta says it does nothing to address the shortage of beds.

“My understanding of the ACA is that it does some great things as far as providing better coverage for mental health treatment, but typically the population of people that we are talking about are the sickest of the sick — people with schizophrenia or severe bipolar disease — and roughly half those people lack insight into their illness,” she says.

“No matter what kind of insurance someone has, if someone doesn’t think they are ill, they are not going to seek care.”

And, of course, having coverage doesn’t help if there’s nowhere to be treated.

“Many Virginians suffer from mental illness only to find a waiting list for services,” Kay Springfield of the Virginia Association of Community Services Boards said in a statement.

“While the instances when individuals must be released because a willing hospital cannot be found are extremely rare, an effective safety net must assure that a broad and robust range of community crisis and inpatient psychiatric services must be available for everyone who needs them.”