In this 50th-anniversary year for the space age, Tuesday marks a critical date in two stages of the "Space Race."

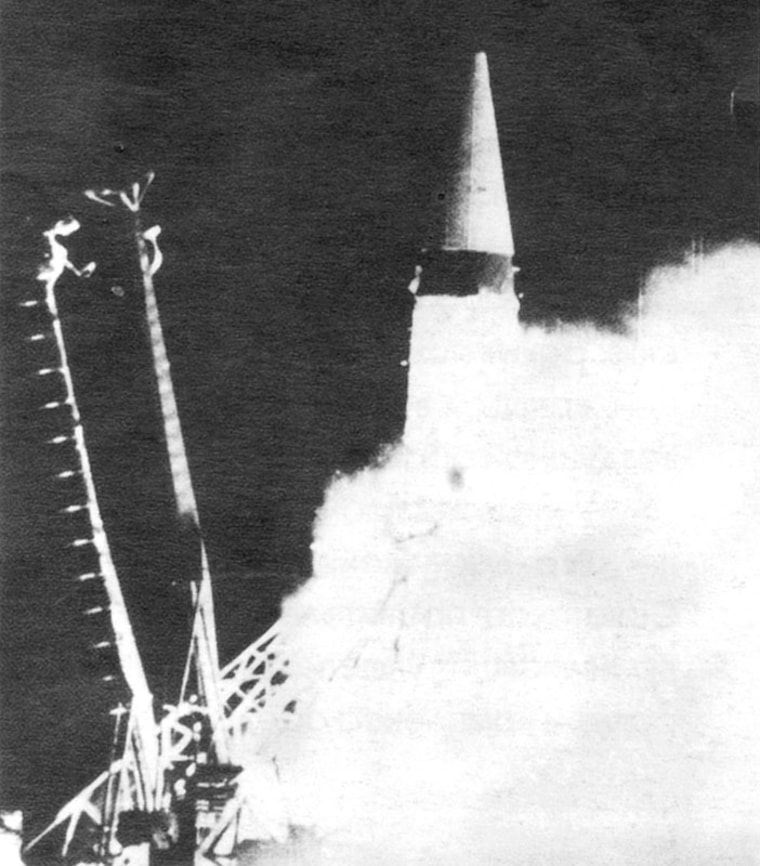

On May 15, 1957, the Russians recorded their first-ever launch of the R-7 space rocket, a design that became (and remains) the mainstay of Russian orbital transportation. That first rocket flew for only a minute or so before exploding, but months later, Moscow officially initiated the space age on Oct. 4 with the triumphant launch of the Sputnik satellite atop an R-7.

Tuesday also marks the 20th anniversary of a Soviet launch — mercifully unsuccessful — that easily could have reset the planet’s space trajectory onto an orbital weapons race that would have wiped out all of the scientific, diplomatic and cultural benefits of the space age.

The first liftoff of the R-7 rocket began a competition that witnessed the grandest conversion of "swords into plowshares" in human history. Weapons of war — the intercontinental ballistic missiles such as the Soviet R-7 and the American Atlas and Titan rockets — were paid for and perfected from military budgets, but fortunately were never used in anger. The missiles soon morphed into carrier rockets for space exploration.

It might have turned out otherwise, and almost did. The first flight of the Soviet Energia super rocket on May 15, 1987, carried a top-secret military payload called Skif-DM — a name that derives from the Russian word for the Scythians, the fierce nomadic horsemen of the Eurasian steppes. The satellite was supposed to have been the opening round of the Soviet "Star Wars" program, aimed at beating the Americans to the deployment of space-to-space missiles and lasers in orbit.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

Had this prototype actually reached orbit successfully and performed preliminary tests, the United States would have correctly identified its purpose, and a vigorous military response would have been politically unavoidable.

On that still-little-known lift-off, the Energia super booster performed well, clearing the way for its use to carry a Buran shuttle on autopilot the following year. But the 100-ton black-painted cylindrical payload suffered a mysterious control malfunction. This made it perform its final rocket thrusts in the wrong direction, and it fell in flames over the Pacific Ocean.

There was no second attempt. Under growing financial strain, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's reformist government delayed and eventually canceled any new "Star Wars" launches.

The Skif-DM debacle was the most beneficial and blessed space failure in the history of the space age, closing off a path that seemed all too unavoidable in the tense closing years of the Cold War. Thirty years earlier, the first R-7 failure was merely a temporary setback, soon overcome gloriously as its successors opened paths into orbit, to the moon and to the nearest planets. May 15 marks both anniversaries.

The flight of the Semyorka

Long before 1957, Russians had dreamed of spaceflight as enthusiastically as had Americans, West Europeans and other imaginative people around the world. But it took a Russian named Sergey Korolev to make the dream into metal with the seventh in a series of each more powerful military missiles.

The R-7 (R for "raketa," or "rocket") was called "semyorka" in Russian slang ("sem" is Russian for "seven"). It was paid for by Moscow in order to enable the slaughter of millions of Americans in a nuclear war. But Korolev, a lifelong spaceflight nut, had other intentions. He built into the rocket features that would prove invaluable for space missions. Many of these features, it turned out, made it such a clumsy weapon that it was deployed only in small numbers and was soon replaced by new generations of missiles from other factories.

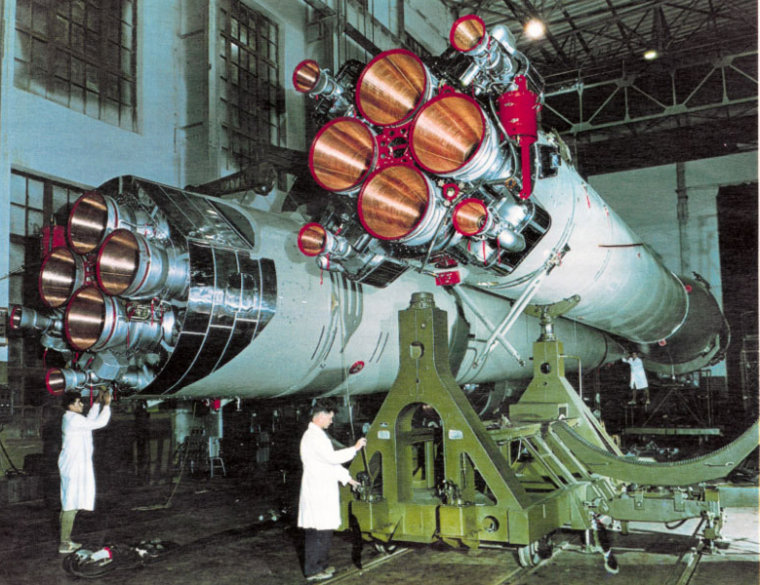

It looked different from every other rocket ever built by humans up until then. Neither long and sleek and finned, or stacked stage upon stage in a tapering tower, it resembled nothing so much as a bundle of fat asparagus stalks. The long central core was flanked by four independent boosters, identical at the business end to the central core but tapering to a point near the top of the core.

This design allowed the missile to have maximum thrust where it needed it most, at launch, when it was lowest, slowest and heaviest. It then could cast off the excess weight of emptied fuel tanks and overpowerful engines when it got higher, lighter and faster.

The “strap-ons” — and the R-7 used the first system of that design — appeared on the U.S. Titan 3 booster a few years later. Strap-on boosters became a key design feature of vehicles such as the Delta, Atlas and even the space shuttle, as well as European, Japanese and Chinese heavy boosters now in use.

But Korolev’s R-7 didn’t just go in for multiple parallel staging — even its rocket engine was "multiple." When the engine designers found they couldn’t build a large thrust chamber with the desired power, Korolev had them build an engine with one set of pumps but four separate nozzles — another innovation that has stood the test of time.

The design proved so robust that it has been upgraded and refined for half a century, and its latest incarnation — the Soyuz-2-1B booster — was introduced only last year. A Soyuz launch pad is being built in French Guiana, making South America the third continent to host the rocket. The production line at the factory in the city of Samara on the Volga River probably will keep building this design for decades yet to come.

Darth Vaderovitch almost strikes back

In contrast, only one space mission ever occurred for the Skif-DM — and that was nearly enough to outweigh all the many hundreds of peaceful "Semyorka" missions.

All of the publicity photographs released after the successful test launch of the Soviet Energia super-booster on May 15, 1987, showed the same side of the massive booster and its two pairs of liquid strap-on boosters. One such view is on a giant 1990 calendar on my study wall, emblazoned with the slogan, "To Space with Peace."

But gradually, descriptions of a dark black side-mounted cylinder, strapped to the other side of the booster, leaked out. It was said to be a mass-scale model of a future space vehicle, or a dummy payload that had merely been carried to stress the ascent profile test — no orbit had been intended.

Years later, Western suspicions about the payload were fanned by photographs that were gradually released, first under Gorbachev’s glasnost ("openness") campaign and later once the Soviet Union had collapsed. Secret Pentagon reports puzzled over the spectacular explosion of the payload when it had fallen back into the atmosphere over the southeastern Pacific—“the biggest infrared signature ever detected by U.S. satellites,” they called it. There were rumors that Gorbachev himself came to watch the launch and was appalled to learn only then of the weaponry being carried. But the ultimate illumination of the project came, fittingly enough, from an independent Russian space historian in Moscow.

Konstantin Lantratov gathered all the bits and pieces of the stories leaking out and visited the factory where the object had been built. He wrote up his results, in Russian, and posted them on a private Russian Web site. Translated by ace American space historian Asif Siddiqi, who specializes in Russian activities, the report is at last being published in a 12,000-word report in two issues of Quest, a quarterly journal on the history of spaceflight.

Orbital battle stations

In illuminating detail, Lantratov chronicles how the payload was thrown together from components of two orbital battle stations already in development. One, the Skif, was to carry a carbon dioxide laser; the other, the Kaskad (as in a "cascade" of rocks) was to carry kinetic kill warheads.

Aiming, stabilization, and power systems were installed inside a hollow Buran fuselage, along with a target dispenser for tracking tests. A special space station module was bolted on the front to maneuver the payload in space. These payloads had been in development since the late 1970s, along with a space shuttle system specifically tasked to service the fleet of orbiting weapons platforms.

Lantratov makes clear that the carbon dioxide laser itself was not flight-ready, so was not installed — for the first flight. But it was scheduled for an orbital test a year or two later.

He also makes clear that Soviet leaders, up to Gorbachev, were thoroughly familiar with the weapons-in-space nature of the payload. They extensively debated how much to actually test in space, with the prospect of detection by American sensors. The main goal of these strategies was to perform as much of the weapons testing as possible while not revealing the nature of the payload — and to allow Soviet diplomats to continue to denounce the American "Star Wars" plan as illegal, immoral and dangerous.

Close call for space warriors

In hindsight, the elaborate Soviet plans to "slip one past" the U.S. sensors look clumsy and ineffective. The suspicious nature of the payload would have been overwhelmingly clear. The American response would have been unavoidable. Such clear-cut and hypocritical "Soviet space treachery" would have irremediably discredited Gorbachev and his reconciliation and reform agenda.

As a result, the Western debate over the desirability of developing space-based weapons would have, for all intents and purposes, ended — in the affirmative. The Freedom space station would have become Fort Freedom, not the international space station. For years to come, Mars would not have been the symbol of a planetary target, but of a classic God of War.

With the stakes that high, there always has been some suspicion that the guidance failure that crashed the payload was no accident, but a deliberate self-destruction to avoid international opprobrium. Yet in his report, Lantratov again delves to an unprecedented depth of new information to explain that the error was in fact entirely unintentional, the result of inadequate checking of control software on a project that was rushed far beyond the bounds of sound space practice. Soviet officials had always intended to orbit the payload, and then to lie about it.

But their intentions, and soon their entire regime, collapsed. Today's web of international space cooperation, however strained and awkward from time to time, is a consequence of that blessed accident. And in almost unbelievable irony, the propulsion unit that doomed Skif-DM was later redesigned as the propulsion unit and base module for the international space station (NASA Web sites reveal no clue about its origin). The module flies on today as part of the home for the latest in a long string of international space crews. And Mars remains a distant target of promise, not of threat.

James Oberg, space analyst for NBC News, spent 22 years at NASA's Johnson Space Center as a Mission Control operator and an orbital designer. He is also an expert on Soviet and Russian space policy and author of the book "Star-Crossed Orbits: Inside the U.S.-Russian Space Alliance."