Top astronomers and other planetary scientists will step into the ring this month to duke it out over a basic, yet controversial, question: What is a planet?

"The Great Planet Debate: Science as Process" conference will be held from Aug. 14-16 at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md.

Some astronomers see the conference as a way of cleaning up the mess created by the organization that names celestial bodies, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), which in August 2006 voted in a new definition of planet that demoted Pluto to "dwarf planet." (Under a more recent IAU decision, Pluto and similar objects are classified as "plutoids.")

Many planet scientists were disgruntled over the 2006 IAU decision, which they said involved a vote of just 424 astronomers out of some 10,000 professional astronomers around the globe. The most recent decision, to categorize Pluto and such as plutoids, further ticked off many astronomers, who felt the term was developed behind closed doors.

"We're going to do something that the IAU did not, which is discuss what we know about planetary bodies in the solar system and around other stars, and discuss the value of different ways of defining objects as planets and what that means," said Mark V. Sykes, director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Ariz.

When the dust settles, those involved hope a consensus will stand, a classification scheme for all objects orbiting a star.

"If a new consensus emerges it will easily overturn the IAU. This is not an issue," said Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the American Museum of Natural History's Hayden Planetarium in New York. "If not, they'll stick with what they've got until something better comes along."

Tyson said he doesn't see the IAU so much as a separate entity, but as part of and a reflection of the astronomical community.

Pluto's part

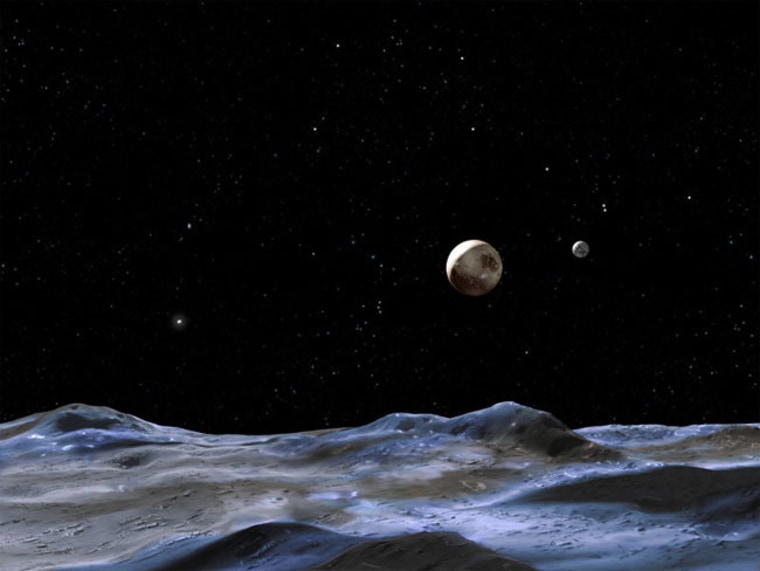

The planet definition saga began, arguably, when Pluto was discovered in 1930, as this object was an oddball compared with its solar system buddies in its eccentric orbit and small size and low mass (less massive than Earth's moon).

The 2004 discovery of Sedna, an object about three-fourths Pluto's size and about three times as far from the sun, raised some questions about Pluto's planetary status. Then, in 2005, Caltech's Mike Brown announced the discovery of 2003 UB313, and bells rang out of a possible 10th planet in our solar system. The object was round, orbited the sun, and the kicker — it turned out to be larger than our then ninth planet, Pluto. Uh-oh.

Since then, the IAU has labeled Pluto a "dwarf planet" and then later, a "plutoid." But some planetary scientists called foul on the way the IAU voted in the new planet definition or the outcome. In fact some vowed to call Pluto a planet despite the most recent IAU ruling.

And so in addition to scientific sessions, the APL conference will include a Pluto debate between Sykes and Tyson. The debate, Tyson says, will focus on Pluto with regard to the mountain of new information being collected about our solar system and others.

"I'm tired," Tyson said. "I've been arguing Pluto for eight years, so it's another occasion where I'm arguing Pluto. This one happens to be a little more formal in its construct. So I see it as another day of just trying to tell people, teach people about, what we now know about the solar system."

Sykes thinks an object should be considered a planet if it's round and orbits a star, which is a definition based on physical features of an object, such as its size and mass. Objects become round when they are so massive that gravity crushes them into this shape, which is in hydrostatic equilibrium (a state where gravitional and internal pressures are in balance). His definition would usher in not just Pluto, but also Ceres (an object in the asteroid belt) and Eris (the current name for 2003 UB313), as solar system planets.

Based on what has worked in the past for planetary scientists, Tyson supports the idea of using "observational features" to put an object on or off the planet list. Such criteria would include distance from its host star, but it wouldn't include what the planet is made out of. Particularly with planet-like objects discovered outside of the solar system, astronomers can't eke out, say, whether the core is made of iron or another chemical, or whether its surface is rocky or not.

It is hard to know what will transpire at the conference with so many top thinkers, Tyson said.

"When you bring a lot of creative, talented people together new solutions can arise that might not have arisen from any one individual," he told SPACE.com. "The collaboration, the intersection of ideas, has its own way of creating new understanding."

What to expect

Sykes and others organizing the conference say the most important aspect of the conference is, well, the conference itself.

"This topic provides the perfect opportunity to teach science as a process, not a collection of facts," said conference organizer Keith Noll of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. "We also need to stress the importance of incorporating new discoveries to continually improve our understanding of the diverse objects within planetary systems."

Hal Weaver, a conference organizer and planetary astronomer at APL said, "No votes will be taken at this conference to put specific objects in or out of the family of planets." He added, "But we will have advocates of the IAU definition and proponents of alternative definitions presenting their cases."

At the end of the day, though, scientists are looking to come up with some sort of consensus on the topic of what it means to be a planet.

"There's a lot of emotion, still a lot of room for opinion," Tyson said, "but it's conferences like this that are hoping to settle the dust and see what remains standing and see if a consensus can emerge."

If a sensible classification system does emerge, Tyson said, it will spread throughout the astronomical community.

The best-case scenario in Tyson's view: "Everyone sings 'Kumbaya' at the end with a brand new classification scheme for everything that orbits a star. That would be really cool."

His worst-case scenario: "Worst case is that people throw tomatoes at each other. There's been some fascinating emotion that has arisen over the past eight years. And I'd be interested to see at what level they express themselves at this conference."