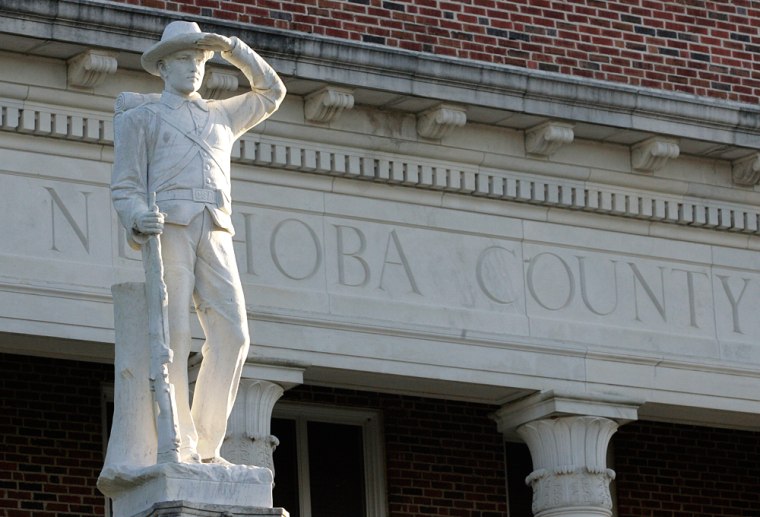

On a small-town Saturday night, a half-block from the town square where a deteriorating Confederate statue stands guard, state Sen. Eric Powell walks into a restaurant for dinner.

Powell orders fried pickles. Bubba Carpenter, a Republican state representative, ambles over with his 5-year-old son, Noah. The two freshmen legislators make small talk about a Civil War reenactment and plans to attend Friday's scheduled debate between Barack Obama and John McCain at the University of Mississippi.

Noah wordlessly reaches his hand across the table, palm up. Powell gently slaps him five, his large brown hand swallowing Noah's tiny white one.

This is the new Mississippi — where Powell, a Democrat, is the first black person ever elected to the state legislature from a rural white district. Where a combination of the murderous past and the nation's largest percentage of black residents have, in some surprising ways, pushed Mississippi race relations ahead of the rest of the nation.

The specter of the past will rise when Obama visits the campus where segregationists fought federal troops to keep James Meredith from integrating Ole Miss in 1962. Obama is fighting his own historic battle for the presidency in the face of what polls indicate is racial prejudice. But the backdrop has changed as these story lines converge.

Bubba Carpenter, whose district adjacent to Powell's has only one stoplight, says people in the area "don't look at Eric as a black man. They knew his character, his beliefs, what he stood for. They elected a person, not a Democrat, Republican, black or white."

Make no mistake, though — Powell is black and knows it. Growing up near Corinth in Tishomingo County, which is 98 percent white, he and his father were once told to order at the back door of a hamburger stand. Recently, Powell and his son were left waiting half an hour for service at a barbecue restaurant.

Everyone in Mississippi, which is 37 percent black, understands that racism lives on. And what of the rest of the country, which is 12 percent black? In a recent AP-Yahoo poll that found racial attitudes could cost Obama a close election, 55 percent of whites said "a lot" or "some" discrimination exists, while almost all blacks felt that way.

Powell, 42, attended integrated schools and got hooked on politics after being elected class president at Tishomingo High in the 10th, 11th and 12th grades. He works at an integrated paper mill and lives with his wife and three children in an integrated neighborhood. He saw blacks elected mayor of Corinth and come within four votes of being elected Tishomingo sheriff.

So when Powell was first asked to run for state Senate in 2003, he was unfazed by his district's 91 percent white and solidly Republican population. Powell lost then by 630 votes. Last year, he ran again and received 8,571 votes, 497 more than his opponent.

"Part of the new Mississippi is you have a group of older people, white and black, that always cared about black people," Powell says. "They're not going to say a whole lot. But they go to the polls and vote."

Echoes of the Civil War

The Civil War Explanatory Center in Corinth documents the pivotal battle for control of the town's railroad junction, which controlled access to a huge swath of the South. "Many northerners viewed slave labor as unfair competition and a threat to their right to make a living," reads one placard at the entrance to the museum. "Few northern whites supported abolition or equality for African-Americans."

Shortly after the battle of Shiloh a few miles to the north, Union troops defeated Confederate forces at Corinth amid carnage that shocked both sides of the young nation. In the museum, photos of Col. William P. Rogers, whose statue stands in the local square, show him lying dead next to his slain horse.

"Other issues remain unresolved," reads an exhibit near the end of the tour. "The debate continues."

There cannot be new without the old.

"Mississippi is probably frozen in time with images from the past," says Charles Reagan Wilson, a history professor at the University of Mississippi and former director of the school's Center for the Study of Southern Culture. "Those are such dramatic images it's hard to forget them, unless you are exposed to the new Mississippi."

Deborah Posey, a nurse from Philadelphia, Miss., can't forget. For years now, she has been stopping at the roadside site in her hometown where three civil rights workers were abducted in one of America's most infamous race murders.

"Blood is on the land, and the land cries," Posey says.

So does Posey, 54, as she recounts her unlikely involvement in the case that helped pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act and inspired the Oscar-winning 1988 film "Mississippi Burning."

She grew up in segregated Philadelphia, "terrified of black males, don't know why, can't tell you why." Her ex-husband's father, Billy Ray Posey, has admitted he was one of the killers, documents show. Her cousin allegedly hid the car used to transport the bodies. For years she was deeply afraid and ashamed of her hometown, and could not believe that justice would ever be done.

Then, in 2004, she joined a multi-racial coalition planning to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the killings. The group's acknowledgment of the heinous crime and call for justice helped spur the prosecution of 80-year-old Edgar Ray Killen, who was convicted in 2005 of manslaughter and received a 60-year sentence.

"I cannot say I've been the same since," says Posey, pressing fingers to her wet eyes.

But before the Philadelphia coalition could begin its work, roadblocks emerged. A debate over calling for a march or a resolution — each one anathema to the opposing racial group — made them realize that a basis of trust and communication was needed.

So for the next six meetings, coalition members simply talked about why they were there.

"Those were the most emotional six weeks of my life," says Leroy Clemons, head of the Neshoba County NAACP. "It was like we lanced this wound and drained the pus from it. For the first time, I understood that white people were just as offended as I was by these killings. And they realized that the black community did not hold them personally responsible."

Clemons and Jim Prince III, editor and publisher of the local newspaper, the Neshoba County Democrat, co-chaired the coalition. They had attended college together at Mississippi State and worked side-by-side at the Democrat, writing stories by day and delivering papers by night.

Writing a new story for county

Their main motivation was to write a new story for Neshoba County.

"We traveled a lot as kids, and you would go places (and say you're from) Mississippi, and people would kind of recoil," says Prince, who is white. "It's something that we have lived with all our lives."

After the Killen catharsis, coalition members turned their attention to other issues — education, jobs, plus the everyday community concerns that can grow from small misunderstandings into full-fledged battles.

When the city approved a bond issue to improve parks, more than $1 million was allocated to build a "fourplex" — four baseball fields back-to-back — in the heart of the black community. The only thing was, the neighborhood league only had eight teams.

"What were they gonna do, play every day?" Clemons says.

The black community identified a better use for the funds: renovating the West Side Community Center and the gym in what used to be the segregated Booker T. Washington school, which had a sentimental attachment for many older black men who once played ball there.

The eight black baseball teams formed a new league with the white teams from across town.

"It feels good to be at the table, for your input to matter," Clemons says.

Walking through the community center, which is almost completed, Clemons shows evident pride. "Will there be Internet access in those rooms?" he asks one workman. Renovation of the swimming pool outside comes next.

Four black men sit in the shade outside the center, wondering whether the pool will be completed. "Leroy said it would," says Leon Baxtrum, 75, speaking of Clemons. "Leroy, they listen when he speaks. He has the ability to work within the system."

They all agreed that race relations in Philadelphia, while not perfect, were pretty good.

"There's probably more problems up (north) than down here," said Curlee Connors, 59. "But you got to have a whipping boy, so why not Mississippi."

Fred Evans, 65, left Philadelphia as a young man to work in Flint, Mich., then lived in California, Missouri and Illinois before retiring back home.

"When I left in the '60s, I hated it here," Evans says. "But things changed."

'Old times here are not forgotten'

"I don't want to be Pollyannish here. Like the song 'Dixie' says, old times here are not forgotten," says former secretary of state Dick Molpus, a Philadelphia native who received death threats after apologizing to the three families at a commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the killings. "But I really do believe Mississippi can be a beacon for the United States to follow when it comes to race."

A statue of James Meredith now stands on the Ole Miss campus, near an administration building that remains marked by bullets fired in 1962. The university is home to a diverse student body and the Institute of Racial Reconciliation, which worked with Philadelphia on its historic resolution.

Republican Gov. Haley Barbour has signed bills to create a civil rights curriculum for public schools and a civil rights museum in Jackson, the state capital. The airport there already bears the name of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers.

Blacks are part of the power structure now, holding 49 of the state legislature's 174 seats, plus dozens of mayor and county supervisor positions.

Yet there has never been a black statewide official in Mississippi since Reconstruction. There are 26 active white hate groups in the state, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. The Council of Conservative Citizens, which opposes racial integration and says America should "remain European in character," recently had 34 members in the state House of representatives, according to the SPLC.

Mississippi knows that racism lives on, which is one reason why it offers powerful lessons about how to move on.

In some ways, the rest of the nation has no choice but to follow.

Whites are projected to be a minority in the United States by the year 2042. In the new Mississippi, whites are expected to be a minority by 2015.