From flooded coastlines to drought and wildfires, California can expect hundreds of billions of dollars in costs from global warming in the decades ahead, according to estimates being compiled for the state's interagency Climate Action Team.

The impact from warming could translate into annual costs and revenue losses throughout the economy of between $2.5 billion and $15 billion by 2050. A summary of cost analyses was presented to Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's climate advisers.

Property damage caused by more devastating wildfires and sea level rise — the water damage alone is estimated at $100 billion in property loss by the end of the century — could push the costs far higher.

The projected financial toll comes from a compilation of 40 studies commissioned by the Climate Action Team. The final reports, which will be released at the end of March, are intended to provide a comprehensive snapshot of global warming's potential costs to property owners, businesses and state government.

If nothing is done globally to reduce emissions, the studies warn, hotter temperatures will lead to rising sea levels that will flood property in the San Francisco Bay area, lead to lower crop yields and water shortages, produce more intense wildfires and cause more demand for electricity to cool homes.

The studies were written by scientists from various disciplines based at California universities and research institutions. They include a range of costs from agriculture, wildfires, water supply, flooding and electricity demand.

480,000 along coast at risk

One of the 40 reports — a look at sea levels and erosion from waves — was released simultaneously with the cost summaries.

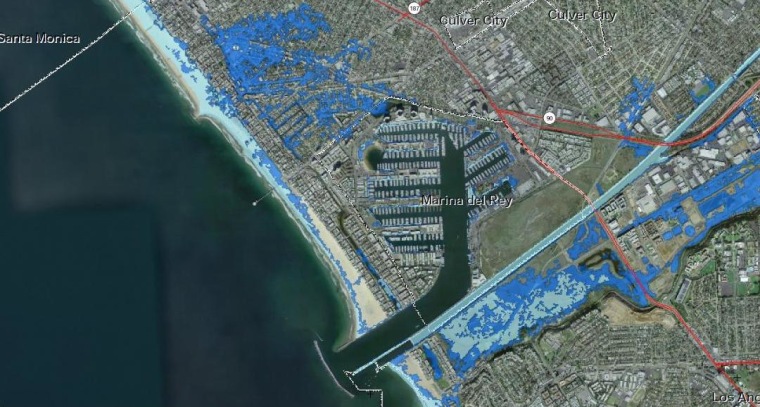

The study by the Pacific Institute estimates that a 5-foot rise in sea levels by 2100 would effect 480,000 people who live in areas at risk, causing $100 billion in property damage.

"An overwhelming two thirds of that property is concentrated on San Francisco Bay," the institute stated, adding that a 5-foot rise is possible if greenhouse gases increase at a pace regarded as a "medium-high" scenario. San Francisco and Oakland international airports are at risk of being under water, as are 3,500 miles of roads, 30 power plants and 29 wastewater treatment plants.

California could also lose 41 square miles of coastline by 2100 due to erosion, threatening the homes of 14,000 people, the report stated. People in San Mateo, Orange and Alameda Counties are most vulnerable.

"Coastal armoring is one potential adaptation strategy," the institute said. "Approximately 1,100 miles of new or modified coastal protection structures — such as dikes and dunes, seawalls, and bulkheads — are needed on the Pacific Coast and San Francisco Bay" to protect against flooding from a 5 foot sea level rise. "The cost of building new or upgrading existing structures is estimated to be at least $14 billion, with an additional $1.4 billion per year in maintenance costs."

The institute added that an "alternative to costly engineering projects" would be "non-structural" responses that "allow natural processes to work, and include a retreat from the most at-risk areas, or deciding not to rebuild flood-damaged properties."

'A lot at stake'

Michael Hanemann, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of California at Berkeley, said "the numbers indicate that we have a lot at stake."

"Californians need to pay serious attention to control our greenhouse gas emissions, and they need to start thinking about adaptation," he added.

Hanemann, who reviewed the studies, said the annual cost estimate of $2.5 billion to $15 billion is conservative.

For example, wildfire property damage estimates do not include money that might be spent by state and local governments to fight the fires.

Wildfire property damage alone could cost Californians between $200 million and $42 billion a year, with the larger figure based on a worse-case scenario, Hanemann said. The state spent about $1 billion fighting wildfires in 2008.

Economic estimates were not available for the small-business sector. The consequences for commercial and recreational fishing as marine ecosystems change or the ski industry if the snowpack gets smaller also have not been determined.

The annual costs also could be greater at the end of the century, ranging from $14 billion a year to $45 billion in 2085.

California's total annual economic output was estimated at $1.8 trillion in 2007, the most recent figure published by the federal government.

The reports come as California regulators are implementing a 2006 state law that requires greenhouse gas emissions to be cut to 1990 levels by 2020.

Linda Adams, secretary of the California Environmental Protection Agency, said the research shows why the state needs to cut carbon emissions aggressively over the next 40 years.

"It will cost significantly less to combat climate change than it will to maintain a business-as-usual approach," Adams said.