Despite the fact that they always seem to wing their way into movies and children’s pop-up books, the truth is that scientists don’t know very much about pterosaurs, the ancient flying reptiles that lived during the days of the dinosaurs. A new species of pterosaur described in this Friday’s issue of the journal Science, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, suggests that some of these creatures may have looked —and behaved — much differently than we’ve imagined.

The past lives of pterosaurs are mysterious mostly because their lightly built and hollow skeletons don’t preserve very well in the fossil record. The nearly complete skull of the new species, dubbed Thalassodromeus sethi, comes from the Araripe Basin in Brazil, one of the few places in the world with large numbers of intact pterosaur fossils.

The fossil-bearing layers are the remnant of a 110-million-year-old lagoon bed, an oxygen-poor environment that slowed the decay of creatures buried at its bottom. The skull was also encased in limestone nodules that acted as a protective jacket around the fragile bones, according to Science researcher Alexander W.A. Kellner of the Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

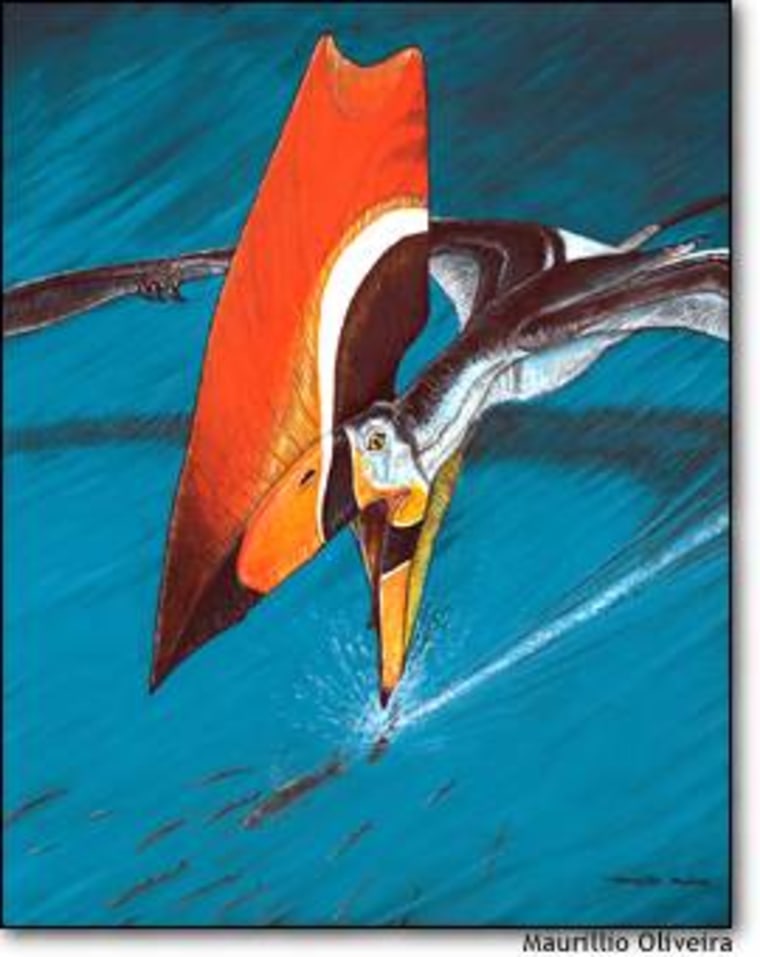

The size of the skull suggests that Thalassodromeus may have had a wingspan of 14 feet (4.2 to 4.5 meters), or about twice the wingspan of a bald eagle. At first glance, its most noticeable feature is the large crest topping the skull. But it’s the species’ elongated and bladelike jaw that gave the species its name, which is Greek for “sea runner.”

Skimming for supper

Thalassodromeus’ whole skull, except the crest, is streamlined and narrow. The lower jaw protrudes in a slight underbite, and the arrangement of the upper “beak” and lower jaw is such that the two halves strongly lock together in a scissorslike fashion. Only one other animal — living or extinct — has such a similar visage: Rynchops, or skimmer birds.

Skimmers do just what their name suggests; they skim over the ocean’s surface, dipping their lower jaw into the water to catch small fishes and crustaceans. To help them in this endeavor, the birds have a distinctive set of neck muscles and blood and nerve supply to the jaw that goes along with their unusual beak anatomy.

The Thalassodromeus skull shows signs of a similar anatomy, with bony scars marking the places where powerful neck muscles attached to the head, and tiny channels in the jaw where blood vessels once irrigated the jaw.

“Other than the three species of Rynchops, no other flying creature has developed this ‘skimming-fishing’ strategy,” Kellner said.

“This shows us the broad range of feeding specialization developed by pterosaurs, and also shows us how little we know about this amazing group of flying reptiles,” he adds.

Keeping a cool head

Thalassodromeus’ huge and elaborate bony crest may hold additional clues to the pterosaur’s lifestyle, according to the Brazilian researchers. The crest is covered in an extensive network of grooves, signs of the crest’s former blood supply. The large number of blood vessels suggests that Thalassodromeus may have used the crest to regulate its temperature, losing body heat to the environment though its decorated head.

Researchers have toyed with the idea that some pterosaurs regulated their temperature through bony crests, but the delicate blood vessel traces — a key piece of evidence in favor of this argument — have never been reported in other pterosaur fossils, according to Kellner.

“Having such a developed crest might have been an advantage to Thalassodromeus, enabling this animal to develop a different feeding strategy like a skimming behavior,” Kellner said, although he notes that skimming and heat loss aren’t necessarily related.

There’s also the possibility that Thalassodromeus used its large crest as a rudder when flying, perhaps to change direction in the air while chasing its prey. The crest is so large that it must have interfered with the pterosaur’s aerodynamics in some way, Kellner suspects. In the future, he hopes to conduct experiments in a wind tunnel to determine the crest’s exact aerodynamic effect.

Kellner and others continue to work in the rich deposits of the Araripe Basin, but progress on the pterosaurs and other fossils from the site is slow. Thalassodromeus was actually first collected in 1983, but its debut was delayed by the lack of money to prepare and study the specimen. Such delays are all too common for researchers in developing countries, Kellner said.