The U.S. government is expressing confidence that the prosecution of Zacharias Moussaoui, the alleged “20th hijacker” in the 9/11 plot, will continue apace in spite of serious troubles in the initial effort to make charges stick. Behind this confidence, however, is a troubling fact: Senior members of al-Qaida captured in Afghanistan and elsewhere, including some providing credible information to their American captors, are telling U.S. interrogators they have never heard of Moussaoui.

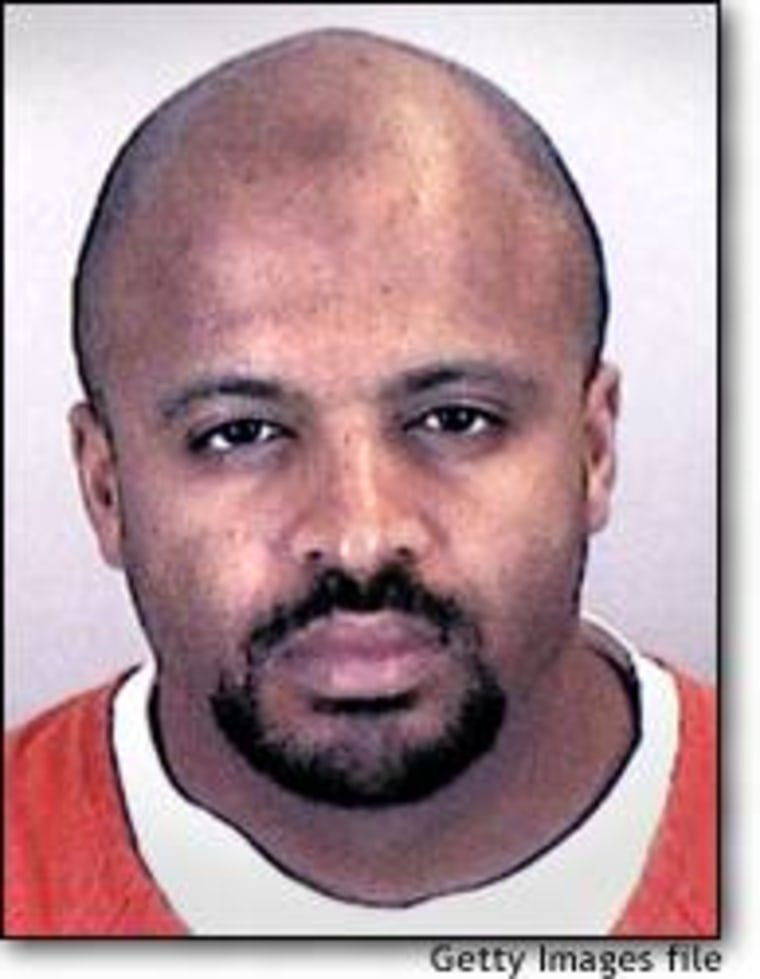

Thursday's announcement that the U.S. government was willing to drop all charges against Moussaoui came as a bit of surprise. The alleged hijacker, 35, is a French national and self-described al-Qaida member and disciple of Osama bin Laden. He also represents the U.S. government’s only arrest in the 9/11 terrorist attacks, though he denies any connection to the plot. This has made his prosecution both legally and politically complicated.

The Thursday offer by the government to drop charges in the trial in Alexandria, Va., however, is more a legal tactic than a statement of real intentions. The Justice Department, facing contempt charges for its failure to provide Moussaoui’s defense attorneys access to captured al-Qaida members, is gambling that an appeals court might be more sympathetic.

If not, this high-stakes case will also become historic, as the United States is hinting that it might declare Moussaoui an “enemy combatant” and try him in one of the highly restrictive, secret and controversial military tribunals set up after 9/11.

Troubling developments

The troubled prosecution of Moussaoui is based, in part, on events in far-off Afghanistan. The ouster of the Taliban there resulted in the capture of senior members of al-Qaida, including the alleged operational planners of the 9/11 attacks. Under a very coercive environment, these al-Qaida figures are starting to talk. What they are saying, however, is making the Moussaoui prosecution more difficult.

From accounts in public documents, it appears that the general theme of the testimony being provided by these captives is, “Who the heck is Moussaoui?”

Al-Qaida’s plot is known to have been highly compartmentalized, and it is always possible these captives are lying. Yet there long has been a suspicion among terrorism experts that Moussaoui seemed out of place when set next to the 19 men who died in the murderous plot that day. He seems too undisciplined, draws too much attention to himself, to have been the member of such a secretive plot.

Upon learning of the lack of corroboration from al-Qaida captives, Moussaoui’s lawyers have sought access to the captives to verify their defense. The government, arguing that the captives are being held in super-secret locations under conditions that cannot be shared, says that allowing a bunch of defense lawyers access to these captives would compromise the interrogations.

The district court judge ruled in favor of Moussaoui’s lawyers on three different occasions. The government has held firm. Facing a contempt order, and an appellate court that would not hear the access question until a final order by the lower court, on Thursday the United States remained silent on the defense request for a dismissal. A ruling is expected soon.

A history of trouble

The Moussaoui case has been torturous from its inception. In fact, long before Moussaoui’s arrest, his name was stirring dissent inside the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He had attracted the attention of the FBI’s Minneapolis field office during 2001 after he enrolled in flight lessons and an instructor found his behavior suspicious. But FBI headquarters ruled there was not enough evidence to indict him or to get a warrant to search his laptop, as the Minneapolis agents desired.

After the 9/11 attacks, Minneapolis Agent-in-Charge Colleen Rawley wrote a scalding memo that alleged that FBI headquarters officials had fumbled the evidence against him and possibly blown a chance to infiltrate the 9/11 plot.

As investigations proceeded after the attacks, the FBI concluded that Moussaoui was, in fact, meant to be the 20th member of the al-Qaida teams that hijacked four airliners that day.

Banking on sympathy

Facing a legal roadblock in its current prosecution, and unwilling to relent on giving the defense access to al-Qaida captives, the government’s strategy now appears to be betting on greater sympathy from the 4th Circuit appellate court in Richmond, Va., easily the most conservative and pro-government court in the land.

For this reason, the federal government generally initiates its terrorism cases in the 4th Circuit. But the government’s gamble is still just that. Even in the 4th Circuit, the government will have to make the case that U.S. national security will, indeed, be compromised if these captives are made available to the defense team. Historically, special provisions have been made in past cases so that such meetings can take place at neutral sites and the government’s concerns for national security are addressed. For instance, defense counsel can be put under gag orders.

A second hurdle the government faces is disproving the defense accusation that this is all merely a ploy to prevent the al-Qaida captives from revealing things that might prove embarrassing. In criminal cases, the government has an obligation to provide any exculpatory evidence that might assist the defense. After all, Moussaoui may not be any American’s idea of an ideal neighbor, but he is facing the death penalty.

The nuclear option

Even if the government loses in the 4th Circuit, it still has one more card up its sleeve. Perhaps no aspect of the war on terrorism has engendered as much legal debate as the administration’s proposal to use military tribunals to try suspected terrorists. These courts, run by the Department of Defense, lower standards of evidence and alter appellate protections, all in secret. So far, no suspect has been tried under such circumstances, but steps are under way to create a courtroom in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where the bulk of al-Qaida and Taliban captives are held. At least one American citizen, alleged “dirty bomber” Jose Padilla, also may be tried by the tribunals.

So far, this is all just legal theory: There have been no tribunals summoned for a trial. If the 4th Circuit refuses the government’s request in the Moussaoui case, however, he may become the test case for these courts.

Legally, Moussaoui’s lawyers will certainly have a viable argument against such a move by claiming the government is engaging in double jeopardy — trying Moussaoui again after having failed to prosecute the first time. What kind of precedent would it set, the argument goes, if the United States can walk away from a case it is about to lose and simply refile in a one-sided court?

Politically, the use of military tribunals will further fuel the opposition that has arisen to steps taken by the Bush administration to alter the fundamental rules of justice in a quest to prevent terrorism.

It is a debate that has permeated questions about the USA Patriot Act, long-term detentions and increased surveillance. Ironically, the administration does not gain much from its right-wing base in being tough on terror; conservatives fear secret governments as much as liberals.

The threat of terrorism, of course, will not be solved by a bunch of criminal cases in a federal court in Virginia. But, as our democratic norms become to be viewed as more and more like a tool of the military apparatus, you don’t have to be a bleeding-heart liberal to be concerned.

After 9/11, there were those who argued that all the rules had changed. At the opposite extreme, critics of the government argued that none of the rules needed to change. In reality, the pendulum between national security and democratic norms swings wildly back and forth. Unlike war, law is slow, boring, meticulous and quite individualized. These questions get resolved on a case-by-case basis, as we are seeing in a federal courthouse in Richmond, Va., where Moussaoui awaits his fate.

Juliette Kayyem is a senior fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government and an analyst on terrorism for MSNBC.