Two American researchers won the Nobel Prize in chemistry Wednesday for studies of protein receptors that let body cells sense and respond to outside signals like danger or the flavor of food. Such studies are key for developing better drugs.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said Robert Lefkowitz and Brian Kobilka made groundbreaking discoveries, mainly in the 1980s, on an important family of receptors known as G-protein-coupled receptors.

About half of all medications act on these receptors, including beta blockers and antihistamines, so learning about them will help scientists improve the way such drugs work.

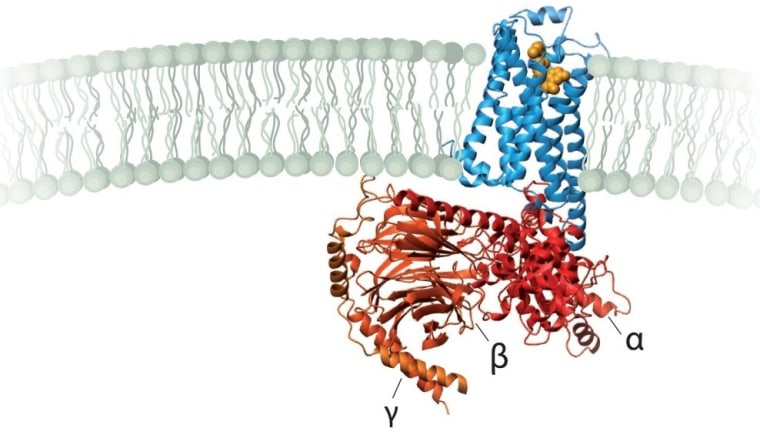

The human body has about 1,000 kinds of such receptors, structures on the surface of cells that let the body respond to a wide variety of chemical signals, like adrenaline. Some receptors are in the nose, tongue and eyes, and let us sense smells, tastes and light.

"They work as a gateway to the cell," Lefkowitz told a news conference in Stockholm by phone. "As a result they are crucial ... to regulate almost every known physiological process with humans."

Lefkowitz, 69, is an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and professor at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C. Kobilka, 57, worked for Lefkowitz at Duke before transferring to Stanford University School of Medicine in California, where he is now a professor.

'Comfortably numb'

Lefkowitz said he was fast asleep when the Nobel committee called, but he didn't hear it because he was wearing ear plugs. So his wife picked up the phone.

"She said, 'There's a call here for you from Stockholm,'" Lefkowitz told The Associated Press. "I knew they ain't calling to find out what the weather is like in Durham today."

He said he didn't have an "inkling" that he was being considered for the Nobel Prize. "Initially, I expected I'd have this huge burst of excitement. But I didn't. I was comfortably numb," Lefkowitz said.

Kobilka said he found out around 2:30 a.m., after the Nobel committee called his home twice. He said that he didn't get to the phone the first time, but that when he picked up the second time, he spoke to five members of the committee.

"They passed the phone around and congratulated me," Kobilka told AP. "I guess they do that so you actually believe them. When one person calls you, it can be a joke, but when five people with convincing Swedish accents call you, then it isn't a joke."

He said he would put his half of the 8 million kronor ($1.2 million) award toward retirement or "pass it on to my kids."

Solving the mystery

The academy said it was long a mystery how cells interact with their environment and adapt to new situations, such as when they react to adrenaline by increasing blood pressure and making the heart beat faster.

Scientists suspected that cell surfaces had some type of receptor for hormones.

Using radioactivity, Lefkowitz managed to identify the receptors — including the receptor for adrenaline — and started to understand how they work.

Kobilka and his team realized that there is a whole family of receptors that look alike — a family now called G-protein-coupled receptors.

In 2011, Kobilka achieved another breakthrough when his team captured an image of the receptor for adrenaline at the moment when it is activated by a hormone and sends a signal into the cell. The academy called the image "a molecular masterpiece."

'Fantastic recognition'

The award is "fantastic recognition for helping us further understand the intricate details of biochemical systems in our bodies," said Bassam Z. Shakhashiri, president of the American Chemical Society.

"They both have made great contributions to our understanding of health and disease," Shakhashiri said. "This is going to help us a great deal to develop new pharmaceuticals, new medicines for combating disease."

Drugs such as beta blockers, antihistamines and various psychiatric medicines have been around for some time, but before Lefkowitz and Kobilka's discoveries, their impact on the human body wasn't fully understood, said Sven Lidin, chairman of the prize committee.

"All we knew was that they worked, but we didn't know why," Lidin said. There is hope that the Nobel-winning research will lead to new medicines, he added.

Mark Downs, chief executive of Britain's Society of Biology, said the critical role receptors play is now taken for granted.

"This groundbreaking work spanning genetics and biochemistry has laid the basis for much of our understanding of modern pharmacology as well as how cells in different parts of living organisms can react differently to external stimulation, such as light and smell, or the internal systems which control our bodies such as hormones," Downs said in a statement.

The U.S. has dominated the Nobel chemistry prize in recent years, with American scientists being included among the winners of 17 of the past 20 awards.

This year's Nobel announcements started Monday with the medicine prize going to stem cell pioneers John Gurdon of Britain and Japan's Shinya Yamanaka. Frenchman Serge Haroche and American David Wineland won the physics prize Tuesday for work on quantum particles.

The Nobel Prizes were established in the will of 19th-century Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite. The awards are always handed out on Dec. 10, the anniversary of Nobel's death in 1896.

More about the Nobels:

- Background on the science behind the chemistry prize

- Nobel physics prize highlights weird world of quantum optics

- Medicine prize honors stem cell breakthroughs

AP Science Writer Malcolm Ritter in New York and AP writers Amanda Kwan in Phoenix, Jack Jones in Columbia, S.C., and Danica Kirka in London contributed to this report.