The Democratic National Committee recently launched a Web site called Kerry Shares Our Values. Designed to reassure supporters puzzled by Sen. John Kerry’s reluctance to share his Catholic faith with the public, the site declares that “John Kerry and John Edwards are inspired by their own religious traditions and share our strong values of faith, family and community.”

The site provides details about the Democratic presidential ticket’s support for “Valuing Families,” “Work with Dignity” and “Concern for the Poor.”

But across the entire site, the word “Catholic” does not appear even once. God Himself is mentioned only in passing, in a section on the environment, where Kerry is quoted stressing the importance of “protecting God’s creation.”

With opinion polls showing a close division among Catholic voters and with conservative activists having denounced Kerry as a “bad Catholic,” prominent Democrats, including some advisers to Kerry, have been frustrated by his reluctance to explain how he is solidly in the mainstream of American Catholic thought.

Too much time was lost last summer, they say, on whether Kerry would be denied the reception of Holy Communion at Mass from one Sunday to the next, a flap that Religion News Service lampooned as the “Kerry wafer watch.”

For them, the issue is not so much whether voters agree with Kerry’s Catholic beliefs, but simply that voters know the depth of his faith and are reassured that Kerry has core principles underlying his politics.

Survey data indicate that voters want to hear what their candidates think about God. In August, the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press reported that 83 percent of Americans said religion was very or fairly important in their lives, while 72 percent of registered voters strongly or mostly agreed that the president “should have strong religious beliefs.”

About the same time, Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research reported that only 40 percent of American Catholics even knew Kerry was Catholic. And according to Pew, only 40 percent of Americans thought the Democratic Party was “friendly toward religion.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, President Bush is leading among Catholic voters, by 13 percentage points in a new Pew survey conducted this month. But nearly all polls show that 8 percent to 10 percent of likely Catholic voters remain stubbornly uncommitted, and many are in three of the most closely contested battleground states: Pennsylvania, Ohio and Missouri. Those voters could represent the Holy Grail of this election.

“It’s astonishing at this point, given Bush’s outreach, that 10 percent are still in play,” said Shaun Casey, an assistant professor of ethics at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, who has advised the Kerry campaign this year. “If you’re still on the fence, you are ripe for the picking.”

The measurement in this race is not where you come from. It is “what do you fight for?”— John Kerry

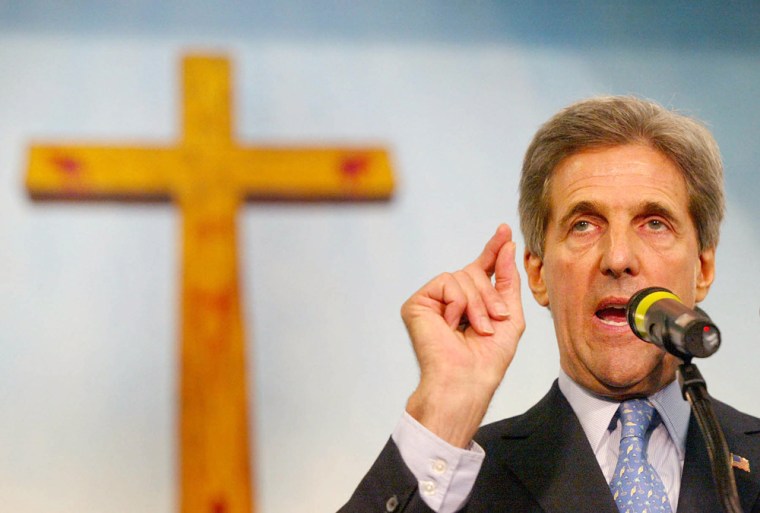

More and more in recent weeks, Kerry has spoken of his “values” in ways designed to connect with religious voters.

“I don’t wear my religion on my sleeve,” Kerry said in his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention. “But faith has given me values and hope to live by, from Vietnam to this day, from Sunday to Sunday.”

He has been reluctant to address the specifics of his faith, however. The campaign has made significant steps toward reaching out to religious voters as pressure on Kerry to speak out has grown — but even so, the silence is notable.

That can lead to messages that seem muddled even though they are consistent and reasonable when viewed from the perspective of an intellectual whose church turned itself upside down just as he was forming his political consciousness.

“I can’t take what is an article of faith for me and legislate it for someone who doesn’t share that article of faith, whether they be agnostic, atheist, Jew, Protestant, whatever. I can’t do that,” Kerry said when asked about abortion at his second debate with President Bush.

“But I can counsel people,” he said. “I can talk reasonably about life and about responsibility. I can talk to people, as my wife, Teresa, does, about making other choices and about abstinence and about all these other things that we ought to do as a responsible society. But as a president, I have to represent all the people in the nation.”

Bush, in response, likely spoke for many voters when he said, “I’m trying to decipher that.”

Among politicians the esteem of religion is profitable; the principles of it are troublesome.— Benjamin Whichcote (1609-83), English religious leader

The difficulty for Kerry is getting the message across that his policy positions are grounded in religious convictions when articulating those philosophies can lead some to conclude that he has none.

In recent weeks, a covey of advisers to former President Bill Clinton have joined the campaign, several of them hoping to connect the Democratic Party with the burgeoning religious progressive revival.

One of them, John Podesta, Clinton’s White House chief of staff, is director of the Center for American Progress, which has organized a project to emphasize the religious foundations of modern American progressivism.

“Whether it’s called faithful citizenship or any of a dozen other terms, it’s the belief that advocating fairness and social justice is not only consistent with a belief in God, but a requirement of it,” Podesta wrote last month.

One of Clinton’s White House press secretaries, Mike McCurry, joined the campaign last month as a top-level strategist.

“I would really like to see Democrats speak genuinely and authentically about how religion and how faith informs the positions we take on so many issues — social justice issues, how we deal with issues that concern the dispossessed, the poor,” McCurry, a Sunday school superintendent and teacher who was a delegate to the United Methodist Church’s legislative assembly last spring, said in an interview with Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly.

Another adviser is CNN analyst Paul Begala, who helped mastermind Clinton’s election in 1992. Begala describes himself as a “religious progressive” who believes American liberalism has become too secular. “[My] faith drew me toward expression in political liberalism,” Begala said in an address last year at Georgetown University.

To decide against your conviction is to be an unqualified and excusable traitor, both to yourself and to your country, let them label you as they may. — Mark Twain

Opinion polling suggests that courting religious voters more openly could pay dividends for Kerry. One way might be to highlight his differences from Bush, not downplay them.

While Kerry’s differences from Catholic teachings have been widely noted, less attention has been paid to Bush's positions that are opposed by his United Methodist Church:

- Bush strongly believes in capital punishment. The United Methodist Book of Resolutions says: “There can be no assertion that human life can be taken humanely by the state.”

- Jim Winkler, head of the United Methodist General Board of Church and Society, denounced the buildup to war in Iraq in August 2002: “I ask United Methodists to oppose this reckless measure and urge the president to immediately pursue other means to resolve the threat posed by Iraq.”

- As governor of Texas, Bush signed a law allowing citizens to carry concealed weapons. His church supports banning ownership of handguns.

- Bush opposes legal abortion except in cases of rape or incest or if the life of the woman is in danger. The church accepts legal abortion as long as it is not used as a form of birth control or to select a baby’s sex.

- The church opposes Bush’s initiative to distribute vouchers that parents can use to send their children to private and religious schools, saying vouchers diminish support for public schools and breach the wall between church and state.

- Bush says he believes gays should not be allowed to serve in the military. His church says they should.

Kerry supporters don’t quibble with Bush’s stands, at least not in relation to United Methodist policy. They object to what they see as the “free pass” Bush gets for his dissent.

There is no movement within Methodism similar to the campaign to persuade Catholic bishops to turn Kerry away at Communion because of his support for legal abortion. And no Methodist official has formally sought to remove Bush from his denomination; in Los Angeles, however, a member of an ecclesiastical court filed heresy charges against Kerry this summer, seeking his excommunication.

Casey, of Wesley Theological Seminary, said in an interview: “I think the mainstream media has taken the bait from some of the right-wing Catholic critics and not held Bush to a similar standard when it comes to his own alleged denomination.”

In a democracy, dissent is an act of faith.— J. William Fulbright

The irony is that being a “bad Catholic” is not necessarily a bad thing to American voters — especially other Catholics, among whom Kerry is squarely in the mainstream, according to polling data:

- Like Kerry, 61 percent of Catholics believe abortion should be legal, according to a survey of Catholics in June by Belden Russonello & Stewart. Even more, 72 percent, said Catholic politicians who supported abortion rights should not be denied communion, according to a Washington Post/ABC News poll conducted in May.

- In May, the Gallup Organization reported that 71 percent of Catholics supported the death penalty, the justification for which the church under Pope John Paul II has said is “practically nonexistent.”

- In opposition to his church, Kerry supports federal funding for research on embryonic stem-cell technology. So do 67 percent of American Catholics, according to a Harris poll conducted in July.

If his beliefs mean Kerry is a “bad Catholic,” as some conservative supporters of the president contend, then so, too, are most American Catholics. But the Kerry campaign has not effectively made that case, having been bogged down on the specific issue of abortion and the “wafer watch.” Podesta, McCurry and other high-profile Democrats are working to persuade Kerry to argue the case himself, and prominently.

“I don’t share the results of the polls that tell you it’s a down side,” said former Boston Mayor Raymond L. Flynn, who was Clinton’s ambassador to the Vatican. Although Flynn has criticized Kerry’s position on abortion and is not endorsing either candidate this year, he helped jump-start Kerry’s political career in the 1980s, and the two were closely allied at times.

“I have a suspicion — I have a feeling; I have a gut reaction — that [voters are] going to say: ‘Well, at least he’s leveling with us. He’s not saying the political thing,’” Flynn said in an interview.

“You know, they’ll tuck their kids into bed that night and they’ll say, ‘You know, I’m glad he’s there making that decision.’”