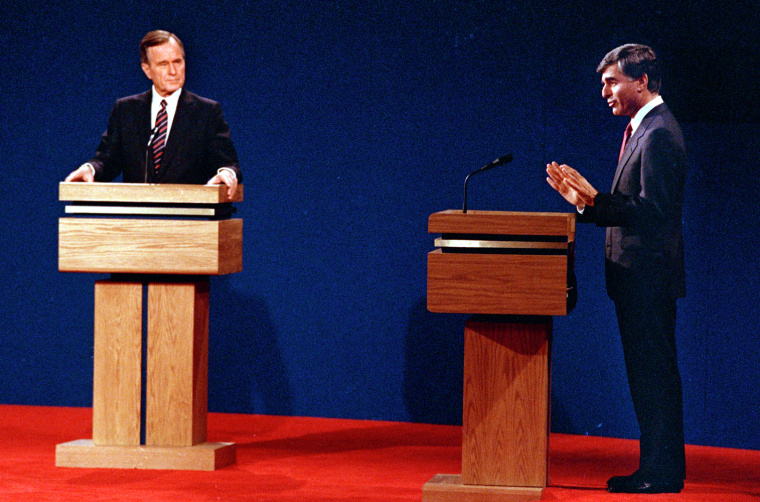

Sometimes you see a candidacy collapse before your eyes on the television monitor in the press room of a presidential debate. At the first one I covered — at UCLA in 1988 — I watched Gov. Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts lose what little chance he had of beating Vice President George Bush.

Bernie Shaw of CNN, a gritty guy who could come at you from weird angles, asked the rather nerdy Dukakis what he would do if he learned that his wife had been raped and murdered. Rather than saying that he would exact bloody vengeance, Dukakis plunged into a monologue about the need to convene a hemispheric summit on drug abuse. I was a few seats away from Tom Oliphant, the mordantly witty reporter for Dukakis' hometown paper, The Boston Globe. "Say goodnight, Mike," Oliphant declared, and lay his head on the table.

It isn't usually that simple. Pivotal moments aren't usually apparent at first glance. They are like an old-fashioned photographic print in a chemical bath; they take time to emerge. Often there isn't a pivotal moment, even a hidden one, so it takes even longer for the press to invent one outright, since drama is what we live on. In 2000, at UMass in Boston, I went on MSNBC after the first Gore-Bush debate and said I thought that Bush had "won" it by not losing it. I was right, as it turned out, but I did not get the real news — which, it became clear after a day or two, was all about The Gore Sigh.

Verdict may take a while

The point is: Without a "say goodnight, Mike" moment, we may not know who "won" tonight's debate until a day or two later.

Now a huge industry has grown up to influence what the press eventually decides to declare the Pivotal Moment. I speak, of course, of the spin doctors. At UCLA long ago, spinners were a new invention, still in their guppy phase. After the debate, a smattering of them circulated through the press area, but they did so gingerly, whispering and cajoling and trying to act all innocent and helpful as they did their work of shaping a story.

It's a madhouse now. Here at the University of Miami, the media are gathered in the campus Wellness Center — an ironic name if there ever was one. An army of spinners has descended on the city, eager to fan out across the Wellness Center to tell the George Bush or John Kerry version of the Wellness of the debate to any reporter who is willing to listen to their spiel.

They don't call themselves "spin doctors," of course (which, by the way, wouldn't be a bad name for the new Washington baseball team). They are "surrogates" or, if they are really fancy-schmantzy, they are "super-surrogates" — meaning they have spun whole cities or continents in their time.

I flew down here with one of the most successful ever: a Republican Washingtonian named Ken Duberstein. Why is he so good? For one, he's not a hack. He had a classy job: White House Chief of Staff in the last Reagan years. Second, he's a nice guy, slow to anger, eager to praise, and deeply, truly knowledgeable. He returns phone calls promptly. When he does, he doesn't make you feel stupid. He treats reporters like colleagues. More important, he is a Republican but not a doctrinaire one; a Bush man but not a slavish one; and he is a valued adviser to two of the media's favorite people of all time, Secretary of State Colin Powell and Sen. John McCain. And Duberstein is quotable, and he is usually willing to admit some version of the truth even if it is an unpleasant reality to him politically. Now he is a big time corporate counselor — a backroom wise man who rarely lobbies on the Hill but rather a CEO's guide to the labyrinth of DC.

'Leadership election'

"They" — the Bush-Cheney campaign — asked him to come down and do some media room spinning. So he was trying out his pre-debate talking points on me as we flew to Miami. He gains credibility by conceding a few points. This is a "leadership election," which favors Strongbow Bush even if all his policies aren't popular. Kerry should actually be way ahead, but is not because he has run a nothingburger of a campaign that has no message. The Kerry campaign has been so inept that Bush and Karl Rove haven't even had to dwell on Kerry's Senate record. And, by the way, no one liked Kerry in the Senate. So "Duperdog," as Powell called him a year ago, was essentially saying that Bush could have been had — but certainly not by Kerry.

My response was: Yeah, but despite the pounding and the crappy campaign, Kerry still isn't out of it because Iraq gets worse by the minute and voters may still want to fire Bush for having taken us there in the first place. Duberstein smoothly kicked into a higher gear in response. The worse things get in Iraq, he said, the better it is for Bush, because it means that his "strong" leadership is all that much more important in a crisis — which Iraq certainly is. Now that's a super surrogate.

But for all their hard work and wily ways, the super surrogates aren't the ones whose words construct the conventional wisdom about a presidential debate. It happens as one reporter and writer peeks over his or her shoulder at what others in the tribe are saying and writing. That process will move faster than ever this year because of the Internet and the blogosphere.

And yet it may take longer than last time for a consensus to emerge. Why? Because there is no longer a "media." There are two, three, many media. Fox will have a take; the New York Times will have a take; Don Imus will have a take. And it will take time for all of them to agree on what they saw with their own eyes.

One other point. The ultimate spin doctors aren't in the Wellness Center but in the polls — the instant ones and the avalanche of them that will follow this weekend. As skillful as Duberstein and his cohorts are, they are no match for "the numbers."