Terri Schiavo has now died. She died amid an incredible cacophony of arguments, pleadings, demands, threats, prayers and commentary. That she died angered many. How she died angered many others. The attention her death elicited from so many different sources angered still others. If in the wake of her passing it is possible to put some of that anger aside, perhaps we can all ask ourselves some hard questions about what has taken place here. What should each of us take away from the incredible events of the past few weeks?

First of all, no one in the United States should be without a durable power of attorney for medical decision-making. Everyone old enough to write down who they want to make medical decisions for them must do so. Every physician must ask every patient. Every hospital and nursing home must ask and record every person’s wishes. Every priest, minister, rabbi and other religious leader must remind their followers to let their loved ones know who speaks for them.

Start a dialogue

It is not enough to write your wishes down. You need to tell the person you have picked that you have chosen them and they need to consent. You need to remember to update your written wishes every few years. You need to make sure that copies of your wishes are in the hands of those most likely to come to the hospital if you are severely injured or become very sick.

Equally important are discussions about life and death. If this case has not already made you talk to your family, friends and loved ones about your views concerning medical care then do so. Now.

Not all will agree on what to do should they or someone they love become severely disabled or lose cognitive abilities. But we need to talk about these difficult matters openly, honestly, calmly and frankly.

Lawmakers overreached

It seems very clear to me that no legislator should be trying to do anything at this point at the county, state or federal level except encourage people to sign durable powers of attorney or living wills. If Congress and the legislators in Florida made anything clear over the past few years of fighting about Schiavo’s fate, it is that they have no idea what they are talking about.

After the spectacle of senators second-guessing diagnoses without benefit of any solid information, a governor introducing people as experts who lacked real credentials or hands-on experience, state legislators giving the spotlight to anyone who had any claim — no matter how blatantly screwy — about how to cure those who are severely brain injured, there is not a legislature in America that is ready to say or do anything useful about the right to stop treatment.

If legislators cannot stand inaction in the wake of what has just taken place, then let them hold hearings in which those with claims to make are carefully cross-examined and the public is given a chance to learn how conditions like permanent vegetative state and coma are diagnosed and why nearly every doctor, nurse and dietician in America knows that a feeding tube is a form of medical treatment.

Inexcusable silence

In addition, organized medicine and hospice care in America need to reflect on their relative lack of participation in the national debate about Schiavo. With the exception of the California Medical Association, the New England Journal of Medicine, which rapidly got some useful articles into print, the American Academy of Neurology and a few other health care groups, few medical organizations spoke out or used this event as an opportunity to teach or explain. Most groups, such as the American Medical Association, were, sadly, nowhere to be found.

And where were the patient advocacy groups and those who represent the interests of the disabled, the chronically sick and the brain injured? Not Dead Yet spoke up and let their views be known. But where were the many other groups who also speak for those with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson's, ALS, cancer, AIDS, spinal cord injuries, cystic fibrosis, Huntington’s disease and numerous other maladies where very hard choices about terminating treatment and even ending the use of feeding tubes have to be made. Ducking commentary on the Schiavo case should not be an option for those with the most experience in decisions to stop care. Cowardice in the face of controversy is not a virtue.

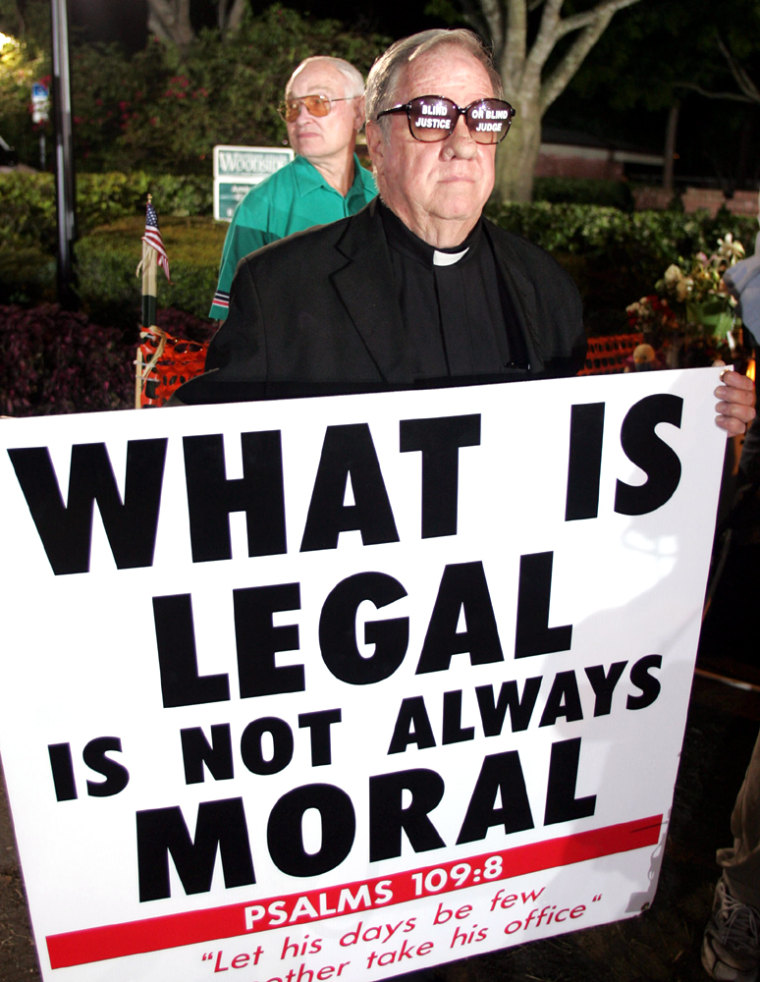

And yes, we heard from the Vatican about its thoughts concerning Schiavo. But where were the Christian Scientists, the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the fundamentalist Protestants who turn to prayer to express their views on the right to refuse any and all medical care including a feeding tube? And what were the views of the Lutheran Church, the United Church of Christ, reform Jews, Congregationalists, Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims, Mormons, Seventh Day Adventists, Unitarians, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians on the right to refuse treatment including feeding tubes? These groups owe it to us to end their silence and to weigh in with their thinking.

Those who suggested that any hospice would ever let a person die a miserable, painful death should simply recant. Hospice is one of the greatest institutions ever to appear in American health care. No one, whatever their motives or goals, should ever be allowed to suggest that those who provide care in hospices do so in a way that does anything other than put the control of pain and the maintenance of human dignity at the forefront.

Respect individual choice and the law

I have my own view on what to do when medicine forces a choice between life and liberty. I favor letting each person make up their own mind about what they want from the health care system. I favor letting competent adults say "no" to ventilators, dialysis machines, CPR, feeding tubes, chemotherapy, aspirin, blood transfusions, antibiotics, physical therapy and even conversations with a doctor. I favor turning to husbands and wives as the decision-makers when a person who once was competent cannot speak. I believe husbands and wives can have their role as surrogate challenged. I favor letting local courts handle disputes in these matters without interference from presidents and governors, the speaker of the House, the Senate majority whip or federal judges. And I favor honoring the law, not disregarding it when there is disagreement about what to do with a patient.

That said, some may argue I am wrong. But, I am not wrong about the fact that Schiavo has given us all a chance to talk and understand more about how to use medical technology to prolong life in hospitals, nursing homes and hospices. Any politician, interest group, educational organization, religious entity or advocacy organization that fails to take advantage of that opportunity is not deserving of any Americans’ support.

Arthur Caplan is director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania.