To mark its 35th year, Electronics magazine broke from its usual coverage of vacuum tubes, newfangled lasers and high-tech minutia to ask a handful of experts to look ahead and write about their vision of the future.

Among the contributors was the young research director of a company that made integrated circuits — a relatively recent advance that combined transistors on a chip and seemed a promising but expensive way to make electronics smaller.

“The future of integrated electronics is the future of electronics itself,” he wrote. “The advantages of integration will bring about a proliferation of electronics, pushing this science into many new areas. Integrated circuits will lead to such wonders as home computers ...”

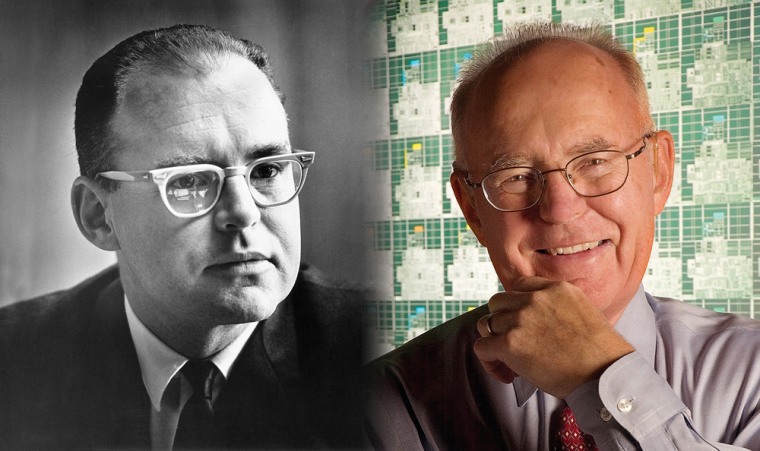

The year was 1965, the author Gordon Moore.

In three years, Moore would leave his job at Fairchild Semiconductor to co-found Intel Corp. His article — “Cramming More Components Onto Integrated Circuits,” buried on page 114 of the now-defunct magazine’s April 19 issue — set the pace for the chip industry, which has become a significant driver of the global economy.

‘It’s what made Silicon Valley’

Over time, the observation would be called “Moore’s Law.” It has set a guidepost for technologists around the world for four decades — and counting.

“It’s the human spirit. It’s what made Silicon Valley,” said Carver Mead, a retired California Institute of Technology computer scientist who coined the term “Moore’s Law” in the early 1970s. “It’s the real thing.”

Plotting curves on graph paper, Moore saw that the number of components on an integrated circuit had doubled every year and figured that rate would continue for a decade as transistors were made smaller. He saw that the per-component costs would fall as manufacturing improved.

“The accuracy of the plot was not my principal objective,” Moore said in a recent interview at Intel’s headquarters, where the former chairman and CEO still keeps a cubicle. “I just wanted to get the idea across that integrated circuits were the route to much lower-cost electronics.”

A powerful forecast

Time proved the prediction to be accurate — so much so that the chip industry’s future plans are based on Moore’s forecast, which he has since revised to a doubling every two years. A corollary has been a commensurate improvement in performance.

The observation is even more impressive given that in 1965, there were just 50 to 60 transistors, among other components, on an integrated circuit, but the growth rate has closely followed his predicted curve to the present day.

At the same time, the cost per transistor has fallen as Moore predicted. In 1954, a transistor cost, on average, $5.52. By 2004, its price tag was a billionth of a dollar.

The implications have been huge, not just for computing but for everything touched by computers. All is now faster, better and cheaper — from desktop PCs that have the processing capabilities that once required a room-sized computer to feature-packed cell phones and portable music players the size of a pack of gum.

Not to mention all the silicon on factory floors, in automobiles and advanced weapons.

“The accomplishment which Moore’s Law represents has been the greatest technological success of human history,” said Stan Williams, a senior fellow at Hewlett-Packard Co.’s research lab. “There isn’t anything else out there that’s ever been such a spectacular improvement in technology.”

Launching a little company called Intel

Moore, a chemist by background, had joined Fairchild after leaving a firm set up by William Shockley, one of the transistor’s inventors in 1947. Robert Noyce, a pioneer in integrated circuits, also was part of the “Traitorous Eight” defectors.

After a series of management changes at Fairchild, Noyce and Moore bolted again — this time forming Intel — short for Integrated Electronics — to make advanced circuits and find new uses for them.

“It was a very courageous thing to do — to believe this doubling could continue on for a significant number of generations,” Williams said. “But he understood it and placed some pretty significant bets — and boy did it ever pay off.”

Last year, Intel reported $34.2 billion in sales. Now retired, the 76-year-old Moore still ranks among the world’s wealthiest people with an estimated fortune worth $4.3 billion. He remains an active philanthropist.

Success industrywide

Success, however, was not limited to Intel. The global semiconductor industry reported sales last year of $213 billion. The consumer electronics industry, which relies largely on semiconductors, pulled in $1 trillion.

On a fundamental level, Moore’s Law gives chip makers, their equipment suppliers and their customers headlights for the future.

But cramming more and more transistors onto a chip is only half the story: Companies are left to figure out how to use them.

Recently, Intel and others have moved toward integrating two processor cores on a single chip, a move that could be planned years in advance thanks to guidance from Moore’s Law, said Fred Weber, chief technology officer at Advanced Micro Devices Inc., an Intel rival.

“The reason we had the confidence five years ago to (announce) our multicore design was because we saw where the number of transistors would move, and we knew what computer architecture would make possible,” he said.

Moore's Corollary: Nothing lasts forever

But, as Moore himself is quick to point out, nothing can grow at an exponential rate forever. Within the next 15 years, it’s expected that engineers will reach the point where any further shrinkage would require atoms to be split.

“Any exponential extrapolated far enough predicts a disaster,” Moore said.

Then again, predicting the end of Moore’s Law has become a favorite pastime in the Silicon Valley. Its demise has been a few years away for the last 20 years, though each seemingly insurmountable barrier has been bypassed.

“There’s been every reason given why it shouldn’t work anymore, every reason why it’s dead, every reason why it’s about to die,” said Craig Barrett, Intel’s chief executive.

Despite Moore’s influence, there’s not a whiff of arrogance about him. As he walked outside the other day, he offered to hold the door for a delivery man who was carrying a handheld computer but didn’t recognize the man who 40 years ago had predicted such technology could exist.

For years, Moore was uncomfortable uttering the words “Moore’s Law,” and he said he is surprised at how his prediction has been adapted — and sometimes mangled — by others. “I’m going to be as well known as Murphy one of these days,” he said.