Jenee Odani had always expected to take care of her parents, just as they had cared for theirs.

In 2011, her mother and father moved into her family home on Oahu, after adding a studio apartment with a partial kitchen and some privacy upstairs. They also remodeled bathrooms on the ground floor to be senior-friendly, with higher toilets and low showers. Someday, when the stairs become too difficult for her parents to navigate, they’ll move downstairs and Odani and her husband, Norman, will move into the studio.

“It made sense for my parents to live closer to me to help me take care of my son," said Odani, 41, whose great-great-grandfather immigrated from Japan. "As my parents got older, the roles might change, and we’d need to take care of them. It was much easier to do that with them living with us."

Asian Americans are twice as likely as whites to live in households with at least two adult generations. They’re also the fastest-growing ethnic group in the country, which means their choices are influencing the future shape of communities in the U.S.

At the end of the Great Depression, about a quarter of Americans lived in multigenerational households. That share fell to a low of 12.1 percent in 1980, before slowly rising again.

“But families who come together by need, have stayed together by choice.”

“We’ve cultivated this myth of independence in this country, and stigmatized individuals and families when they rely on each other,” said Donna Butts, executive director of Generations United, a Washington D.C. advocacy group that promotes programs and policies to connect people of different ages. “But families who come together by need, have stayed together by choice.”

About 51 million, or one in six Americans, live under this arrangement –- roughly 23 percent of blacks, 22 percent of Hispanics, and 13 percent of whites. The latest recession fueled the trend, as families weathered tough times by moving in together. Much of the change is also cultural, based on immigration trends over the past twenty years, said Stephen Melman, director of economic services at the National Association of Home Builders.

“We have seen plans for upscale one-story homes which build in an ‘in-law’ suite so that the older adults can help out with the family, and the younger adults provide the ‘heavy lifting’ such as shopping,” Melman said.

Odani’s parents, Howell and Judith Ching, have transformed the unruly yard into a verdant garden, make household repairs, and maintain the wireless network. They often pick up her son, Nick, 9, from school, and prepare him for sports practice and other extracurricular activities, which allows her to work longer hours at a veterinarian's office.

Odani has fond memories of her own grandparents, who lived next door to her childhood home, and in turn, is grateful her son is getting to know her parents, their personalities and idiosyncrasies. “They tell him stories about what I was like growing up, and I think that helps him more clearly see the role that we each play in our family.”

“They tell him stories about what I was like growing up, and I think that helps him more clearly see the role that we each play in our family.”

Dahlin Group Architecture is working on multigenerational plans in every community it designs, no matter how big the home, said Donald Ruthoff, a senior architect. At Sorrento East in Dublin, California, plans include a bedroom and bath on the first level of the home because a predominance of buyers had multigenerational families -- for families with elderly parents who have difficulty navigating stairs, and for boomerang kids moving home after college.

Likewise, Lennar, a national building developer, is rolling out “NextGen” designs it calls the future of housing. Available in 201 communities across the country, the “home within a home” features a separate entrance, bedroom, with its own bathroom, laundry, eat-in kitchenette, and living room. Year-over-year, sales of NextGen units grew by 58 percent in the second quarter of 2014, with an average sales price of these larger homes 39 percent above the company’s average.

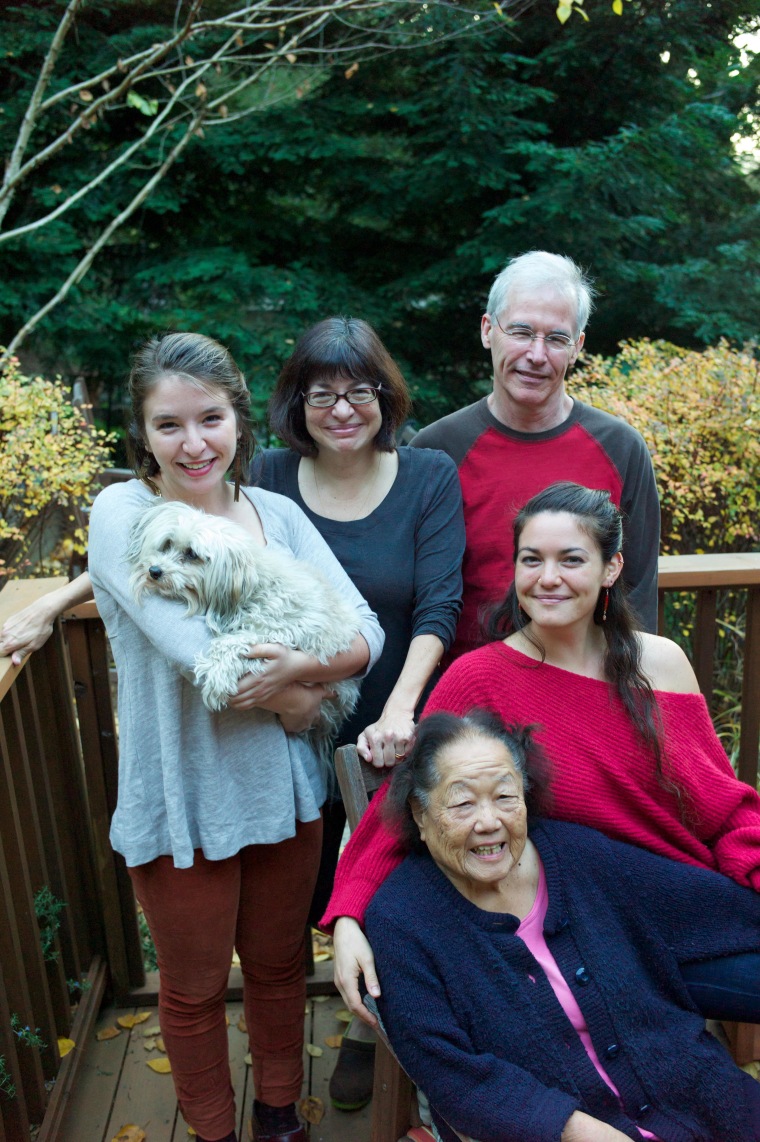

After Susan Ito’s father passed away, her mother, Kiku Ito, visited California frequently, but kept her home in New Jersey. Ito worried about her mother living alone across the country. Eventually, they both sold their homes and moved into a larger place in Oakland in 2004, with enough room for Ito, her husband, their two daughters, and Kiku.

Although Kiku had her own private bathroom and porch, the rapid change disoriented her and she once ran away on foot. Fortunately, they found her, unharmed, but the transition was stressful for both mother and daughter.

“It’s like having your parent on every date of your life, at every dinner...It’s intense.”

Now Kiku, 91, is part of a Japanese-American bowling league (she bowls 180, with a 15-pound ball), and works on quilts with the help of an in-home instructor Ito found. Challenges remain.

“A kid will accept a babysitter, but she won’t accept that,” said Ito, 55, author of the new memoir, The Mouse Room. She has to be “sneaky," she says. She told Kiku she hired a personal chef, but in truth, the woman serves as an occasional caregiver in the afternoon, taking her grocery shopping and asking her to prepare rice or chop vegetables, to make her feel useful.

After Ito’s husband retires, they want to travel, and are still figuring out how they can leave Kiku for a week or so at a time. “It’s like having your parent on every date of your life, at every dinner,” Ito said. “It’s intense.”

But a duty, a tradition she wants to uphold. When she was a child, her maternal grandmother lived with them on the weekends, joined them on vacation, and Kiku did her bills. “We did everything for her, and that really imprinted on me.”