East Los Angeles, CA — In a neighborhood that is almost entirely Latino, a bilingual community newspaper has drawn national attention for its coverage of local issues such as gentrification, affordable housing, immigration and police brutality. But the reporters being recognized for their work are not experienced journalists, but young Latinos from area high schools.

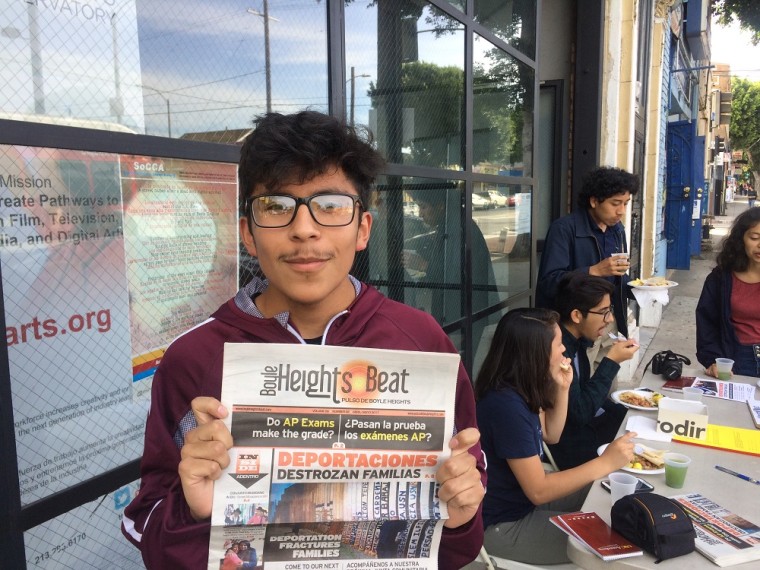

The Boyle Heights Beat, also known in Spanish as El Pulso de Boyle Heights, has carved out an important place in an area with one of the highest population densities in the city of Los Angeles.

East L.A., where Boyle Heights is situated, is approximately 97 percent Latino.

A few years ago, two prominent Latino journalists decided to do something about the lack of coverage when it came to issues in this neighborhood.

“Boyle Heights was not adequately covered by mainstream papers like the Los Angeles Times,” said Michelle Levander, the founding director of the USC Center for Health Journalism. She co-founded and published the Boyle Heights Beat along with Pedro Rojas, former executive editor of Los Angeles’ Spanish-language newspaper La Opinión. “So we thought, who knows a community better than its youth?” said Levander.

Levander and Rojas are deeply involved in the Beat, overseeing everything from reporters’ pitches to front-page decisions. The Beat was founded in 2010, and their first edition came out in June 2011.

Although it is a hyper-local endeavor, the Beat has drawn national attention. It has won praise from The New York Times and the Columbia Journalism Review, and has been featured in the Los Angeles Times.

The young reporters of the Beat have interviewed Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti (who made good on a campaign promise by giving them an exclusive interview after he was elected), the chief of police, and area politicians.

"Who knows a community better than its youth," says one of the newspaper's publishers.

At a recent forum organized by the paper, Zola Cervantes, 17, took a breath before sharing a personal story with the audience gathered at the Boyle Heights Arts Conservatory. Her father was deported in 2010, she recounted, and since then her family spends every weekend travelling to Mexico to visit him. It is a journey she has now made over 100 times, one that she recently wrote about for a community newspaper. Switching between English and Spanish for the benefit of the 60 people seated before her, Cervantes was thoughtful and poised.

But when an audience member asked her how she had dealt with the separation all these years, Cervantes shifted slightly on her feet. “Before doing this story, I thought I had accepted it,” she said, in Spanish. “After I wrote it, I realized that this was not the truth.”

Cervantes’ story about her father’s deportation is on the cover of the latest edition of the Beat. She told NBC Latino that working on the paper has been rewarding.

“I feel like the best part is going out there and learning what it is to be a journalist,” she said. "I didn’t really realize how amazing that experience would be until I was practicing it.”

Young people who are interested in writing for the Beat must live or go to school in Boyle Heights, fill out an online application and go through an interview process. They do not have to have experience on their high school newspaper.

But The Beat requires a serious commitment, according to Levander. “The youth reporters are required to attend two newsroom meetings a week, in addition to working on original stories,” she said. “When young people are first accepted into the program, we run a journalism ‘boot camp’ for them, teaching them the basics of storytelling and things like journalism ethics, what is a ’lede’? what is a ‘nut graph’?”

The print edition of the Beat comes out quarterly, while the online edition is updated regularly. Their circulation is about 33,000. Funding for the Beat’s annual budget of roughly $230,000 comes from the California Endowment, the USC Good Neighbor Campaign, and donations.

Related: ‘Ovarian Psycos’: Young L.A. Latinas Forge Activism, Empowerment Through Biking

“Our goal is not necessarily to produce future journalists,” Beat co-publisher Pedro Rojas told NBC Latino. “Our goal is to give these kids from an underserved community opportunities to develop as citizens and as leaders.”

Still, several of the youth reporters interviewed by NBC Latino indicated a strong interest in pursuing careers in journalism in the future.

Rojas is proud when he sees the Beat’s reporters maturing. Oftentimes, new reporters are shy when they first come to the paper, their only writing experience consisting of homework assignments. “Then a few months later, we see them interviewing the mayor or local politicians,” said Rojas. “They are true reporters.”

Rojas also notices a growing public consciousness among the youth reporters. One of their reporters, he said, once admitted to having little to no interest in politics or current events. Now that same young man attends school board and community meetings and sees himself as an advocate.

Brittny Mejia, a metro reporter for the Los Angeles Times, said that the Beat was a consistent, credible source of information about Boyle Heights. “When I first started covering the east side, I referred to them a lot, “ she said. “I feel like they are really connected to what is going on, plus they do a lot of outreach with the town halls.” The fact that the Beat can land interviews with local lawmakers, she said, indicates that they are taken seriously as a news outlet.

Mejia cited Zola Cervantes' first-person story about her dad’s deportation as an example of “a story they (The Beat) did really well.”

Abel Salas, editor and publisher of Brooklyn & Boyle, a community newspaper focusing on arts and culture, stated that he was impressed by the work of the Beat reporters. “I admire that they are so active in the community; I see them around, reporting on immigration sweeps or other controversies,” he said. “They are the next generation of communicators.”

“They have established themselves as a legitimate media vehicle for Millennials and post-Millennials,” Salas said. “I would be happy to publish some of their work, in fact, if any of them wanted to do a freelance piece for me.”

Related: Mass Deportation Would Cost Families,U.S. Billions: Study

Youth reporter Alex Medina, 17, believes that the work of Boyle Heights Beat is important. “Often the media doesn’t look at minority or low-income areas,” he said. “The mainstream media just covers big stories, but they don’t look at the local heroes, the local stories, and things that are important to places like Boyle Heights.”

Last year, Medina wrote about Mi Centro, an LGBT Center in Boyle Heights, which resonated with him because he identifies as part of the LGBTQ community. After his story appeared, several people told him that they had no idea that such a place existed in Boyle Heights, and that his article had helped open their eyes to the struggles of LGBTQ youth.

“That made me happy,” Medina said, “feeling that I was helping other people.”

In addition to Levander and Rojas, the youth reporters work with three adult mentors who help them shape their stories and accompany them on interviews. After each print edition comes out, the Beat holds a community meeting to hear feedback on their stories and suggestions for new ones.

Youth reporter Saul Soto told NBC Latino that being a part of the Beat had changed his own view of Boyle Heights.

“Before I joined the Beat, I wasn't really aware of issues in my community. I was just kind of like, I live here, whatever. But doing the Beat has really shown me a deeper appreciation for the community, for where I come from, and for where the community comes from,” said Soto. "It's given me a newfound love for this place and I love it. I really love it.”