Attorney General Jeff Sessions says he wants to maintain contracts with private prisons because he's concerned about meeting the federal correctional system's "future needs." But he hasn't said what those needs might be.

The answer may lie in the Trump administration's hardline approach to immigration enforcement.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons' 20-year relationship with privately run lockups hinges on the housing of immigrants. Almost all of the 21,405 people currently serving time in one of those low-security facilities have been designated as "criminal aliens" ─ non-citizens who will likely be deported after they serve their sentences, according to bureau statistics.

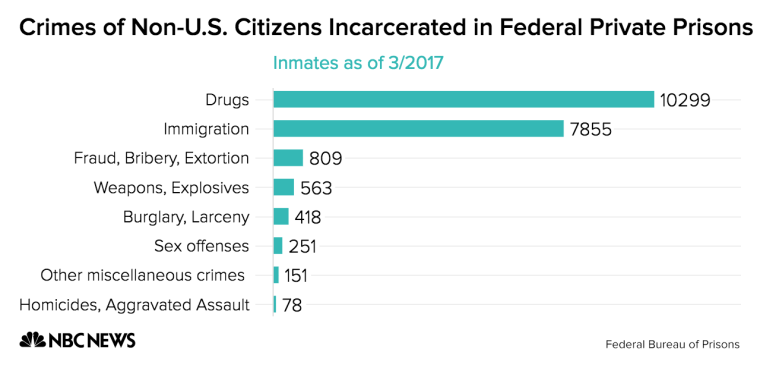

Most have been convicted either of drug offenses or of immigration-related crimes, such as trying to re-enter the United States after already being deported, according to the agency.

That pool of inmates has declined in recent years. But the numbers could turn upward again as Sessions' Justice Department, along with the Department of Homeland Security, seek to prosecute more people who are in the country illegally.

On Feb. 20, DHS Secretary John Kelly outlined his agency's approach to enforcing immigration laws. The staff memo called for a crackdown at the southern border on a range of immigration crimes, ranging from illegal entry and illegal re-entry to drug dealing and human trafficking ─ including the parents of children who are brought over the border by smugglers.

A day later, Sessions rescinded an Obama administration plan to phase out Bureau of Prisons contracts with private prisons, saying it "changes long-standing policy and practice, and impaired the Bureau's ability to meet the future needs of the correctional system."

A Justice Department spokesman did not respond to a request for an explanation of Sessions' memo.

A history of zero-tolerance

Immigration advocates say they fear a return, and then some, to record levels of criminal prosecutions under the Obama administration for illegal entry and illegal re-entry, which now outnumber all other federal prosecutions.

Related: Private Prisons: Here’s Why Sessions’ Memo Matters

That could include an expansion of "zero-tolerance" programs that saw prison as a way to deter illegal border crossings from those trying again after they were released and deported. One such program was called Operation Streamline, which rounded up migrants and brought them before judges in groups for guilty pleas.

But immigrant advocates say the threat of prison was not enough to stop migrants seeking to rejoin their families in the United States.

"What they've told us is, 'My entire life is here, so no matter what happens, I'm going back,'" said Carl Takei, senior staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union's National Prison Project.

The initiative, which began in 2005, has waned in recent years.

Sessions says that was a mistake.

At his Senate confirmation hearing in January, Sessions said he hoped to restore Operation Streamline, saying it has "great positive potential to improve legality at the border."

The result could be more immigrants getting sentenced to federal prison, straining a system that, despite having reduced the inmate population for three consecutive years, remains over capacity.

That could prompt a renewed reliance by the Bureau of Prisons on private facilities.

Sessions' statements, including the Feb. 21 memo, "imply that more beds will be needed in the future, and that's very concerning," said Edward Chung, vice president for criminal justice reform at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank.

But the interplay of Justice Department policies, prison logistics and inmate assignments are complicated, so it is difficult to predict how any single administration action will impact the population of private prisons.

Randy Capps, director of research for U.S. programs at the Migration Policy Institute, cautioned against assuming that more immigrants will pour into private prisons. While border agents could refer more immigrants for criminal prosecution, he said, it will be up to prosecutors and judges in those areas to move cases through the courts. That depends on having enough courtroom and detention space to accommodate them.

"One of the appeals of the private prison system is it's less expensive and is able to expand more quickly," Capps said. "But how and when and whether this translates into more people in prison, I don't know."

Private prisons' rise

The 20,625 so-called "criminal aliens" housed in Bureau of Prisons-contracted private prisons are low-security inmates, largely serving time for non-violent offenses: immigration crimes, drug crimes, fraud, burglary. A small percentage were convicted of weapons offenses, sex offenses or homicides, according to the bureau. They are predominantly Mexican.

Another 20,000 or so incarcerated people who are not citizens are doing time in traditional Bureau of Prison institutions, for similar or more serious offenses, the statistics show.

The companies that stand to benefit from the crackdowns are the same that run dozens of immigration detention centers across the country under contract with DHS ─ prison-like facilities that hold people who've been designated for removal from the United States.

Two that are publicly traded, The GEO Group and CoreCivic, formerly known as Corrections Corporation of America, have seen their stock climb since Trump's election, including a bump after Sessions' Feb. 21 memo. A third, smaller, private provider is Management and Training Corporation. Together, their contracts with the Bureau of Prisons totaled $639 million in fiscal year 2014.

Their relationship with the Bureau of Prisons dates to 1997, when harsh federal sentencing laws stretched public prisons to capacity. The Bureau of Prisons began funneling non-citizens into the for-profit facilities.

For many years, the populations of those private prisons grew, the result of aggressive drug prosecutions nationwide and stepped-up crackdowns on the border. Operation Streamline and similar immigration enforcement strategies were pivotal to that growth, according to analysis by the Pew Research Center.

The private-prison population topped out in 2013 at nearly 30,000.

Then things began to turn, driven mostly by changes to drug policy ─ the relaxing of sentencing laws and a softer approach to low-level drug offenders. But developments at the border also played a role. Migration slowed, and the number of people prosecuted for immigration-related offenses declined, according to TRAC, a Syracuse University program that collects immigration court records.

The federal prison population began to drop, along with the government's need for private facilities.

At the same time, there were growing concerns about the for-profit lockups.

Several of the facilities have been cited for safety and security issues, including disturbances or riots. A 2016 report by the Justice Department's inspector general found that these issues occurred more at private facilities than at comparable Bureau of Prisons-run facilities.

The companies complained that it was an unfair analysis, because the concentration of immigrants, including a higher prevalence of gangs, made the prisons harder to run.

In 2014, the American Civil Liberties Union published the results of an investigation that alleged private prisons in Texas offered far less rehabilitative programs and work opportunities than Bureau of Prisons-run institutions. A bureau spokesman responded by saying that that non-citizens were a better fit for those facilities instead of U.S. citizens because "there are somewhat fewer programs offered to prepare offenders to successfully reintegrate in U.S. communities."

Immigration advocates interpreted that remark to mean that rehabilitation didn't matter for offenders who weren't expected to stay in America.

In August 2016, the Obama Justice Department announced it was going to phase out its contracts with private prisons, citing the declining inmate population and the history of troubles. The department predicted that by May 2017, the number of inmates housed in them would drop to less than 14,000.

Now all that might change.