In recent weeks, some prominent economists have pondered the idea that the current economic shock brought on by shutting down much of the American economy could trigger not just a recession, but a longer, deeper and more damaging event.

Even as the U.S. tiptoes towards recovery, with more states reopening and businesses resuming operations, the prospect of an economic collapse along the lines of the Great Depression can’t be entirely ruled out, experts say.

“The economy has passed the apex of the shock,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. As the Memorial Day holiday nears and business and consumer activity are reestablished, he said the economy can expect to regain some momentum — albeit at a slower rate than pre-COVID.

But Zandi added one significant, worrisome caveat. “If there's a serious second wave as businesses reopen, which is a clear risk, then we’re going back into recession, and this period will go down as a depression. I think the most likely scenario is that we avoid a depression, but the risks are awfully high.”

“Really, the key thing is going to be virus spread,” as the country inches towards reopening, said Eric Freedman, chief investment officer at U.S. Bank Wealth Management. “If we get into an environment where we just see transmission occur more quickly and we don’t have a widespread antiviral treatment or vaccine, that would really lengthen the recovery period,” he said.

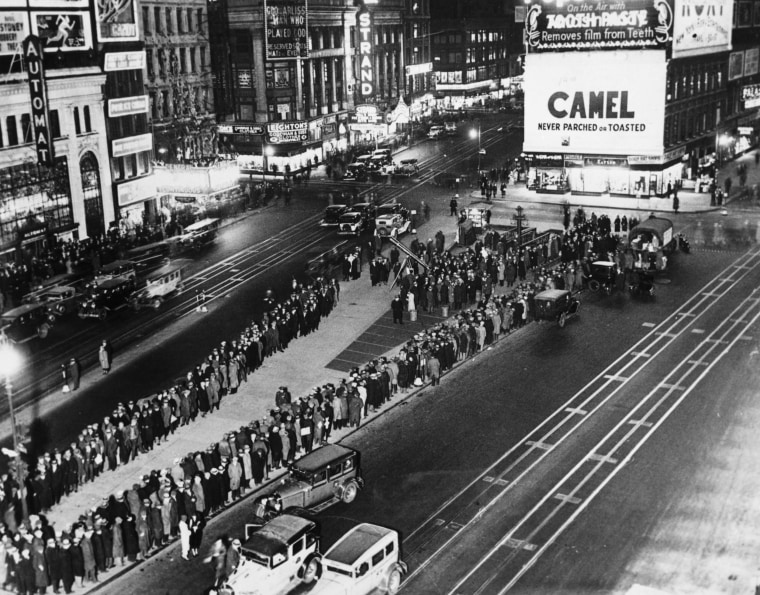

To be sure, some hallmarks of the current economic catastrophe already bear an uncomfortable resemblance to those of nearly a century ago. The speed and severity of the COVID-19-induced economic shock has some key economic metrics already rivaling those not seen since the 1930s, said Constance Hunter, chief economist and principal at KPMG.

“In terms of a decline in GDP, it rivals the Great Depression. The thing that’s going to differentiate if this is a depression or just a very deep recession is how long it takes us to get out of it,” and how many businesses fail in the interim, she said.

“It took three and a half years, from August of 1929 to March of 1933, to go from robust full employment to the depths of the Great Depression,” said Lawrence White, an economics professor at New York University. “The speed of the descent is unprecedented.”

Recessions — traditionally defined as two consecutive quarters of GDP contraction — are fairly regular occurrences, with 11 taking place between 1945 and 2009, with an average of roughly 11 months between peak and trough. The Great Depression was remarkable both for its depth as well as its duration, with nearly four consecutive years of contraction followed by an economic malaise that lingered until the start of World War II.

“If there's a serious second wave as businesses reopen, then we’re going back into recession — and this period will go down as a depression."

But there are some important distinctions between then and now. Today, there are a host of policies in place designed to prevent the economy from sinking into a years-long slump like the Depression, when one in four workers were jobless, many households lost their savings when banks collapsed and the stock market lost nearly 90 percent of its value.

In addition, both the Great Depression and the Great Recession were kicked off by asset deflation. “Those burst bubbles tend to create a longer recovery period,” said Dan North, chief economist for North America at Euler Hermes, because policymakers have to spend valuable time figuring out what went wrong before recovery operations can begin.

“Here, you’re dealing with something that in some ways has elements of a natural disaster, which creates a different dynamic,” said Mason B. Williams, a political science professor at Williams College.

In this case, policymakers know in theory what has to be done to restart the economy, North said. But those assumptions could be upended. The unpredictable epidemiological trajectory of the coronavirus leaves a wide array of outcomes still in the cards. Economists think this could herald a sea change in how Americans spend, save and invest their money — changes that will reverberate potentially decades into the future.

To the extent that lenders will face hardship when homeowners, credit card customers and highly leveraged businesses default on their debts, the Federal Reserve and its counterparts in other countries today have the tools to contain the fallout.

“Banks have strengthened their positions substantially since 2009 and although there will be a rise in non-performing loans, central banks and governments have been swift to ensure that liquidity and solvency of the system is maintained,” said Sarah Hewin, chief economist, Europe and Americas, at Standard Chartered Bank in the U.K.

Many of today’s monetary policies were created in response to events that exacerbated the Depression: Unemployment insurance, for instance, sustains at least some of the demand that vanishes when joblessness spikes and people have no income to spend.

“We’ve entered this crisis with a set of policy tools that came out of the crisis of the 30s and 40s,” Williams said. “The idea of stimulus, of macroeconomic management, more sophisticated monetary policy — all those are legacies of the Depression that will be very useful to us in the current crisis.”

“We entered this crisis with a set of policy tools that came out of the crisis of the 30s and 40s: Stimulus and sophisticated monetary policy are legacies of the Depression that will be very useful to us in the current crisis.”

This is not to say a recovery necessarily will be quick. In a prolonged downturn, the relationships between worker and employer, creditor and borrower, and landlord and tenant all break down, and reestablishing those commercial relationships takes time. “All of those things need to be rebuilt, and it doesn’t happen overnight,” White said.

And this could fundamentally change the way Americans relate to money for decades to come. “After the Depression, we had a whole generation of people who were more likely to save for a rainy day,” said Joseph Mason, professor of finance at Louisiana State University. Especially with the threat of viral recurrences and subsequent outbreaks, “I can certainly believe people are going to want a little bit more of a nest egg socked away,” he said.

Economists speculate that a flight to caution on a scale not seen since the World War II era could alter how Americans approach everything from home buying to saving for retirement — potentially threatening the rebound in consumer spending that drives domestic economic activity. “I think it’s a fairly long-term reduction, which is going to drag on growth,” Mason said.

“We have had a very lucky 80 years in the sense that we have had no war on our soil and we have had uneven, but growing, living standards for many decades,” Hunter said. “COVID-19 changes things in terms of risk… something humans had to deal with in much greater quantities before World War II. This will impact spending and savings patterns and it will impact investment decisions,” she said.

“The wealth effect is a major thing in the U.S., especially after a huge run in equity prices,” said Alon Ozer, chief investment officer at Omnia Family Wealth. “The biggest risk is that the fixed income markets, corporate debt mostly, and equities are going to start to move together,” he said. Investors who don’t have several years to wait for a recovery could be driven to eschew even so-called safe haven investments, curbing companies’ ability to raise cash or issue debt.

“The stuff we see is just staggering,” Ozer said. “What the Fed has to do is basically continue what they're doing, but on a larger scale. They have to make sure that credit growth continues. If credit growth in the U.S. contracts, we're going to have serious problems.”

Ryan Detrick, senior market strategist at LPL Financial, predicted that the total price tag of supporting the economy, already well into the trillions of dollars, could grow even more massive in the coming months. “We could see as much as 30 percent of GDP in the form of monetary and fiscal stimulus,” he said.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell urged lawmakers to consider more fiscal stimulus in his virtual testimony before the Senate Banking Committee on Tuesday.

North said it was unusual for the Fed — an institution that has a long tradition of being apolitical — to address legislative activity so directly.

“He clearly sees some urgency,” North said.

Zandi was less circumspect about the need for Congress to act. “If lawmakers don't pass another rescue package soon, the odds of going back into recession and depression will significantly increase,” he said. “The most likely scenario is that it ends up being a recession, but the depression risks are uncomfortably high and very hard to handicap.”

Much of that uncertainty has to do with as-yet-unknown variables regarding future viral outbreaks. “If the COVID-19 numbers start looking worse with the lockdown restrictions eased, that’s the biggest concern to me,” North said. “That’s a huge downside risk,” he said, since a reluctance by Americans to resume shopping, eating out and engaging in other consumer activities would slam the brakes on any recovery momentum.

“Since it was precipitated by a medical pandemic, it’s going to take a medical solution to really bring the economy back 100 percent — or people are going to have to be comfortable with a lot more risk,” Hunter said.