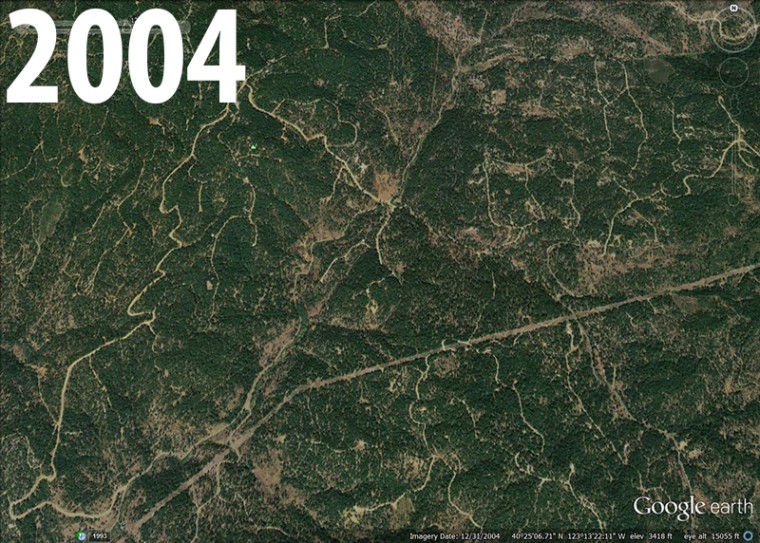

Eleven years ago, the Basin Gulch in California bore the typical topography of the state’s northern woods, with green forests veined by brown trails. But take a look at a Google Earth image from today and the land appears pockmarked by lesions.

“Those are all marijuana fields,” said Paul Ramey, a staffer for California Assemblyman Jim Wood, whose district encompasses much of the ideal wooded grow areas in the state’s far north.

Recent pot-legal states like Washington and Colorado can look to California as a cautionary tale: a brew of pesticides, clear-cutting, water diversion and years of little environmental oversight on its production has given marijuana a particular notoriety among environmentalists, and hasn’t done much to burnish pot’s au naturel brand.

Its effects were perhaps felt most intensely last year during the state’s drought.

Marijuana, which consumes up to about 23 liters of water per plant per day -- about twice that of the state’s prized grapes -- is a particularly thirsty plant. Law enforcement and researchers say that growers, licit or otherwise, routinely flout water laws, diverting and damming streams and rivers and sapping formerly replete local watersheds.

And after being redirected, the flows stay that way.

“Once the pipes are diverted to the grow site, it’s diverted there forever,” he said Mourad Gabriel, a researcher with the Integral Ecology Resource Center in Blue Lake, Calif.

Of urgent concern to conservationists is the survival of the Pacific fisher, a weasel relative and one of a few species whose diminishing population has been linked to rodenticide used on illegal sites clandestinely scattered throughout the state’s national parks. Plants there are frequently sprayed pesticides like, like Furan, a banned “systemic” rodenicide that acts by infiltrating the entirety of the plant by being absorbed in its root. Furan finds their way into the food of endangered or threatened animals like the marten, the white spotted owl, and Pacific fisher, of which there are estimated to be from 500 to 1,500 left in Northern California.

In a 2015 study published in the journal PLOS ONE, Gabriel found 85 percent of all Pacific fishers had been exposed to some kind of fatal rodenticide, up from 79 percent in 2012. In that time, the fisher mortality rate tripled from under six percent to more than 18 percent.

The cause, he says, is the response of illegal growers to the crackdowns: Once large, consolidated grow sites have splintered into myriad smaller ones in less conspicuous reaches of the state’s forests, exposing more potential sites of Pacific fisher food to more chemicals.

And legal sites aren’t always much better when it comes to environmental impact, officials say.

“If you are looking at this from an environmental focus, short of the importation and use of banned chemicals, the statistical data is the same generally,” said Chris Soots, an officer with the California Fish and Wildlife Department.

“Both use mass amounts of fertilizers, divert natural run-off waters, create toxic run-off waste and byproducts, remove large amounts of vegetation and trees, grade hillsides, create loose sluffing and unstable soils, and kill or displace wildlife, either to prevent predation or for consumption.”

Most frustrating for wildlife officials, in the case of illegal sites, are the chemicals and damming that go unfixed once the growers are arrested or run off the land. Gabriel said that cleaning up a single site costs between $30,000 and $40,000. Multiplied by what’s estimated to be at least 2,000 sites, the remediation of illegal sites alone is conservatively calculated at $120,000,000 per year.

But legal sites have been difficult to even secure access to. Property laws make it difficult for academic researchers to investigate the sites, and state officials say they don’t have enough staff to make sure every legal grower complies.

The mounting frustrations have spurred lawmakers to action.

A current bill introduced by California state assembly Assemblyman Wood would levy an excise tax on medical growers to fund the remediation of toxic sites and the fixing of diverted waterways. It would also fund education to teach legal growers how to comply with environmental regulations and enforce violations against those who don’t.

The bill, estimated to raise $60 million per year, was cleared in the Revenue and Tax Committee on Thursday. Hezekiah Allen, the executive director of the California Growers Association, which represents the state’s medicinal growers, said in a statement that the bill “is the right tax at the right time."

Taylor West a director for the National Cannabis Industry association, said that while that organization doesn’t take positions on specific legislation, “It’s important to all of us in the industry that cannabis cultivation be done in ways that minimize negative environmental impacts."

Until recently, the negative effects of marijuana cultivation were "a dirty little secret of that industry,” said Kathryn Phillips, the director of the Sierra Club’s California chapter.

“Perhaps because the impacts have become so overwhelming---particularly on water and wildlife--lawmakers and regulators and some parts of the industry are finally starting to address them.”