Retailers are now in the throes of processing billions of dollars in returned holiday gifts, but many of those items aren’t going back on shelves. Instead, they’ll be bundled off to warehouses and sold in auctions for a fraction of their sticker prices.

More than 15% of the $966 billion in purchases nationwide this past holiday season will be returned, the National Retail Federation estimates. Many of those goods will be scooped up by liquidators in the “reverse supply chain” business, an industry that has been growing thanks to the e-commerce era’s generous return policies.

The reverse logistics market, which includes all players involved in processing in-store or online returns, was valued at $939 billion in 2022 and projected to grow at a 12% compounded annual rate through 2032, according to a Polaris Market Research estimate in August.

Many big brands have tried to make returns as free and painless as possible, and consumers haven’t hesitated to take advantage. Insider Intelligence projected in October that $627 billion in merchandise would be returned over the course of 2023, up more than 26% from 2020’s volumes and comprising 8.5% of total retail sales. The share of returns attributed to e-commerce was expected to rise from 33.7% to 34.3% over that period.

Returns can be costly for retailers. Many already eat the expense of return shipping by providing prepaid labels or envelopes. For certain items, some retailers “just find that it’s not worth it to take it back,” shopping expert Trae Bodge said.

About 59% of retailers reported offering returnless refunds over this holiday season, according to returns management provider goTRG. While those “keep it” policies typically apply to cheaper purchases, Bodge said she has begun seeing some brands, such as Wayfair, allowing customers to keep higher-cost items like furniture.

To handle the many items that do get sent back, retailers are increasingly turning to companies like Liquidity Services, which sorts through a crush of returned goods and resells many of them to other businesses and consumers — sometimes for just 20% of their original prices.

In its over-100,000-square-foot warehouse in Pittston, Pennsylvania, pallets full of pool noodles, floor tiles and kitchen sinks arrive by the truckload. When the loading bay doors open, employees begin sorting through the tens of thousands of pieces of merchandise that arrive each day, inventorying the products, photographing them and assessing what shape they’re in.

“We’re taking items that have come out of their first life, and we’re making them available for people to buy,” said Jeff Rechtzigel, vice president and general manager of Liquidity Services’ retail business.

Consumer brands have long faced criticism that many returned goods wind up in garbage heaps or incinerators, and reverse logistics providers say they’re trying to reduce how much gets destroyed. “It’s a good way to keep items out of landfills and be part of the circular economy,” Rechtzigel said.

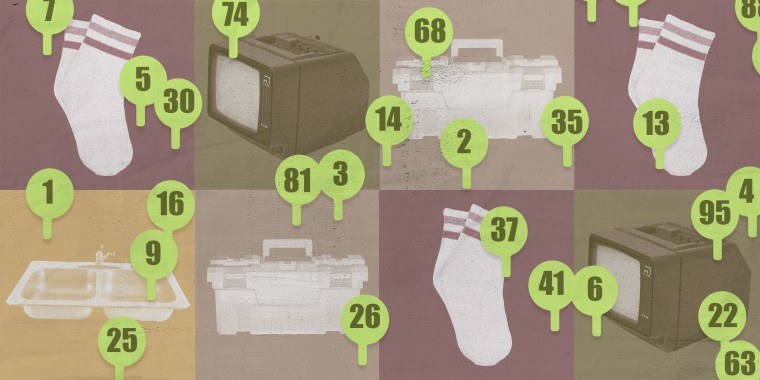

Many unwanted products are in perfectly fine condition, he said, suggesting that 70% to 80% of returns are the result of simple remorse. But there’s still value even in the minority of items that are broken or defective. Toolboxes with massive dents or even televisions that don’t turn on can be resold as damaged and in need of refurbishment, or just for scrap parts.

“Even if it’s not functioning, there’s likely a buyer market that will turn that nonfunctioning item into a working item,” Rechtzigel said, adding that 99% of what Liquidity Services receives is ultimately sellable.

Products are listed online for people to bid on, and auction winners can pick up their items at a nearby warehouse location. Some listings are for entire pallets of similar items sold together in large, plastic-wrapped bundles. The bulk purchases sometimes appeal to retailers when inventory is tight and they need help filling shelves, the company said.

Liquidity Services’ consumer-facing business is part of the growing ecosystem of “bargain bin” resellers, which includes outlets popular on TikTok that sell overstocked and returned items, often to people looking to flip them for a profit.

Stacey Adam said she makes the trip to Liquidity Services’ Pittston warehouse just about every week. She buys home products by the pallet, purchasing items at up to 90% off and reselling them to her community on Facebook at around 50% off, pocketing the difference.

“They’re getting a deal, we’re all getting a deal,” she said.