Two studies released Wednesday point to separate ways to manage the deadly and incurable AIDS virus — not a complete cure, but perhaps a way to save patients decades of having to take multiple pills every single day.

In one approach, doctors have treated two infected newborns with strong cocktails of drugs, driving their virus into near invisibility.

In the second, they have “edited” patients’ immune systems to resist the virus.

Neither approach could be called a cure just yet, and neither will offer a solution for most of the millions of people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. But one approach offers hope for babies born infected, while the other might lead to a viable way for at least some patients to manage their disease.

Dr. Deborah Persaud of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore updated a meeting of AIDS experts on the case of a child, now 3½, who made headlines a year ago when her doctors reported they seemed to have “functionally cured” her with heavy doses of HIV drugs soon after she was born.

The toddler is still doing well and hasn’t needed to be treated with any more drugs, Persaud told the Conference on Retroviruses.

And she said a second child, now 9 months old, is also healthy after being given a similar treatment four hours after she was born.

Doctors don’t know if the very early treatment somehow keeps the virus from taking hold in the body. They want to study more babies to see if strong treatments right at birth might save them from a lifetime of taking the drugs. But they have to wait for the unusual case of a mother giving birth without knowing she is infected, or, as in the case of the second baby born in California, of a mother who did not take her own HIV drugs as directed.

“Like any medicine, you don’t want to be on anything at all."

There is no vaccine and no cure for HIV, which infects 1.1 million Americans and 35 million people worldwide.

Cocktails of drugs called antiretroviral treatment can control the infection and keep it from destroying the immune system. They can also reduce the risk that someone will infect others. And someone who is HIV-free can protect himself or herself by taking them every day.

However, a very few people have a natural immunity to HIV and doctors have been trying to find a way to replicate this.

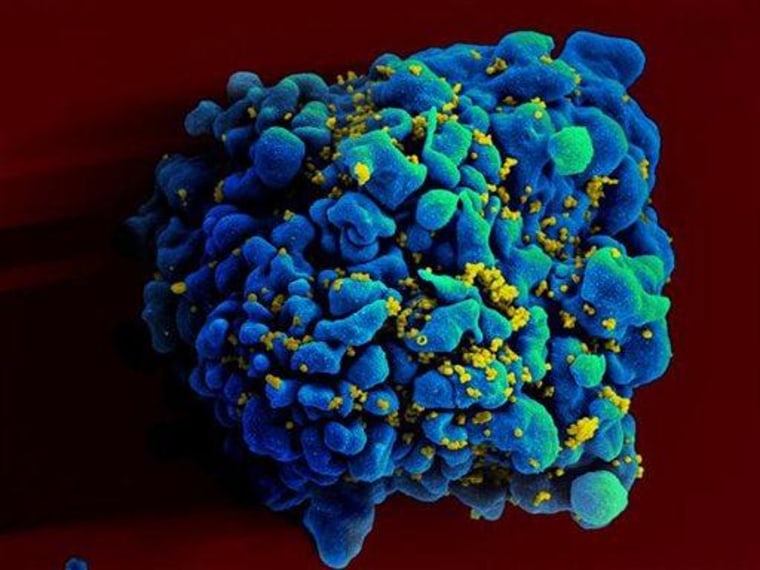

HIV needs to use a type of molecular doorway, called a receptor, to get into the T-cells that it attacks. It uses one called CCR5, and people with a certain mutation of CCR5 are less likely to be infected with HIV.

Many have wondered: What if you could make this mutation in other people, AIDS patients or people at high risk of infection? Would they naturally resist the bad effects of the virus?

A team at the University of Pennsylvania has been doing this and they’ve reported on 12 volunteers who got through the experiment safely.

Dr. Carl June and colleagues took some T-cells from their patients and used an advanced gene therapy technique called gene editing to make them to carry the CCR5 mutation that they wanted. Then they infused them back into the volunteers. It was only a small percentage of all their T-cells, so the idea wasn’t to cure them or stop the infections, just to see if it was safe. And it was, they report in this week’s issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The hope is that these edited T-cells will flourish and multiply and eventually make the patients resistant to the virus. It hasn’t happened just yet — in most of the patients, the virus started to proliferate again after three months off their drug cocktails.

Jay Johnson is one of them. The 54-year-old AIDS organizer has been taking HIV drugs since 1991, but volunteered for the study in the hope of one day being free of having to take pills twice a day.

“Like any medicine, you don’t want to be on anything at all,” Johnson, who lives in Philadelphia, told NBC News.

"It would be like choking out a fire.”

Johnson was the only one of the 12 patients to have a bad reaction to the treatment, which involved taking his blood, separating out the T-cells, genetically altering them, and then infusing them back in. He had what’s called a transfusion reaction.

“That was very scary,” he said. “The transfusion took maybe four to five minutes. (Then) I started feeling chilly.”

He was given drugs to counter the reaction, but then the pain started. “The next thing I know, my whole body went into cramps,” he said. More drugs finally stopped the reaction.

“If that’s the worst of it, and (this treatment) is going to work, I can live with that,” Johnson said.

June said he believes Johnson had the reaction because of the way his team “edited” the T-cells, using a virus. They’ve come up with a way he thinks will be safer, and will try the new method on the next batch of patients.

“What we are hoping to do is increase the amount of these modified cells in patients,” June told NBC News. “If we just put enough in it would be like choking out a fire.”

In theory, the genetically engineered cells should survive better in a patient with an active HIV infection. The virus would kill off the normal cells, leaving only the edited, resistant cells, to survive and multiply. Eventually, the virus wouldn’t have any more cells to infect and would go dormant.

But you cannot ethically leave a human being with an active, untreated HIV infection. June thinks if they can get enough of the altered T-cells into a patient, that might be enough.

“We need to get there and we have to take small steps,” he said.

“The real show-stopper will be a vaccine.”

It seems like an extreme and expensive approach, but June says it might pay off someday.

One way to cure a very difficult cancer is to destroy the immune system and start all over again, with a bone marrow transplant. Researchers have tried to cure HIV this way, but it has only worked in one patient so far, the so-called Berlin patient.

But transfusions of blood cells, without destroying the bone marrow, would be a far less dangerous and far less expensive approach. And given that it can cost $1 million for a lifetime of HIV, it might be cost effective, June argues — especially for a young patient newly infected.

“This is an important study,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “But it’s too soon to say how expensive or practical it is.”

But Fauci said he is encouraged to see all 12 patients are doing well.

More experiments will have to be done — on more patients, and “editing” more of their cells. It’s not a treatment that will help anyone soon, and it’s unlikely that it could ever be used on large numbers of patients. It’s still much easier to give people pills to control the virus and to protect them from infection.

And Fauci likes to remind everyone that the No. 1 goal would be a vaccine that prevents infection in the first place. “The real show-stopper will be a vaccine,” Fauci said.