Michelle Jordan’s son Timothy was dying, and she was running out of options to save him.

The 13-year-old had suffered greatly from sickle cell disease since birth. Episodes of excruciating pain. Blood transfusions every three weeks, then every two weeks. Damaged kidneys. A stroke at age 11.

Doctors in Summerville, South Carolina, where the family lives, told Jordan that Timothy’s only hope was a potentially risky type of bone marrow transplant using a partially matched donor. But the doctors lacked the expertise to do that.

So one day in 2016, Jordan, now 47, packed Timothy in her car and headed for a place where doctors were doing partial-match bone marrow transplants for sickle cell patients: Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

She did not have an appointment. She just drove.

Like Broken Glass in Your Veins

Healthy red blood cells flow easily throughout the body, acting like a trusty mail carrier delivering oxygen to tissue and organs.

People with sickle cell disease have a mutation that deforms the cells into a sickle shape and causes them to become sticky and clump together, clogging small blood vessels. That means oxygen can’t reach tissue and organs. It can cause a variety of life-threatening complications — not to mention extraordinary pain.

“Imagine twisting a rubber band on your finger until it turns blue,” said Dr. Christopher Gamper, a specialist who performs pediatric bone marrow transplants at Johns Hopkins. Others have described it as feeling as if broken glass is trying to move through your veins.

Sickle cell disease, the most common inherited blood disorder in the United States, affects an estimated 100,000 Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dozens of potential drugs are in the pipeline, but the research is a long way off from clinical use. For now, treatments are usually limited to pain management and blood transfusions.

A bone marrow transplant — in which stem cells are taken from a healthy person’s marrow and transfused into a patient with sickle cell anemia — would ideally overhaul and replace a patient’s blood and immune systems.

But finding a bone marrow donor whose immune system perfectly matches the patient’s is difficult, if not impossible. “The chances of finding someone who is an immune match are highest with people of a similar ethnic background,” Gamper told NBC News. “There's a smaller number of people on the [bone marrow] registry who are ethnic minorities.” Sickle cell disease mainly affects people of African descent.

The transplant process is grueling. Patients must endure chemotherapy and radiation to destroy their immune systems. And it carries the risk of rejection, which can be fatal.

It’s also the only potential cure for sickle cell disease, a disorder that usually kills people around their 50th birthday.

100 Hospital Visits, Only One Cure

It was the word “cure” that caught the attention of Dagny and Hans McDonald of Charlotte, North Carolina. Their teenage son, Jensen, had a story similar to Timothy’s. Severe pain. Regular transfusions. At age 10, Jensen’s tissues had deteriorated so badly that he had to have a hip replaced.

Dagny McDonald has trouble calculating the number of times Jensen has been in the hospital. “Easily 100 times. Probably more than that,” she said. Every time sickle cell patients have a fever spike, they’re told to head to the emergency room. Fever is a sign that the body is trying to fight an infection. Patients can’t do that effectively because the disease affects the immune system.

Pain also sends patients to the hospital. “The only way to alleviate the pain is with drugs through an IV. They give you fluids to push the blood cells through,” explained McDonald, 52. “You’re fine until it happens again. And eventually, it does happen again.”

The McDonalds tried alternative ways of easing Jensen’s discomfort — even when he was a baby, whimpering in obvious pain. “We would play music. We would do massage. We would turn down the lights. There is nothing you can do,” his mother said.

A few years ago, they started focusing on the one thing they could do: the bone marrow transplant. They could not find a perfect match for Jensen, so they turned to the doctors at Johns Hopkins doing transplants from partially matched donors.

New Technique Expands the Donor Pool

Johns Hopkins pioneered a technique in the early 2000s that vastly widened the pool of potential bone marrow donors for sickle cell disease patients. Parents are automatically a half-match to children. Siblings can also be partial matches.

“That was a game changer,” said Gamper. Now patients had access to donors who weren’t available before. The Johns Hopkins team spent years tweaking medications and timing of procedures, eventually finding that giving a dose of a chemotherapy drug called cyclophosphamide after the transplant greatly increased the success rate.

Timothy was in bad shape when Michelle Jordan rolled into the Johns Hopkins emergency department that day back in 2016. It took physicians a year to get him stable enough for a transplant. Jordan had raised Timothy since he was an infant, but biologically, she is his aunt. Timothy’s donor ended up being his older sister.

Timothy endured physical setbacks, like pneumonia, after his transplant. But a year and a half later, he’s healthy enough to go to school. He plays football. He dreams of becoming a Navy Seal.

The Promise of a Life Without Pain

LaShanta Whisenton, 40, of Washington has a similar story. In 2010, she was a busy, working mother of three. She did not have time for the complications of sickle cell disease that had plagued her since birth. Birthdays and holidays were cut short because inevitably, Whisenton would develop severe pain and be taken away in an ambulance. She wanted to pursue a transplant, but both her parents had died, and she did not have any matched siblings.

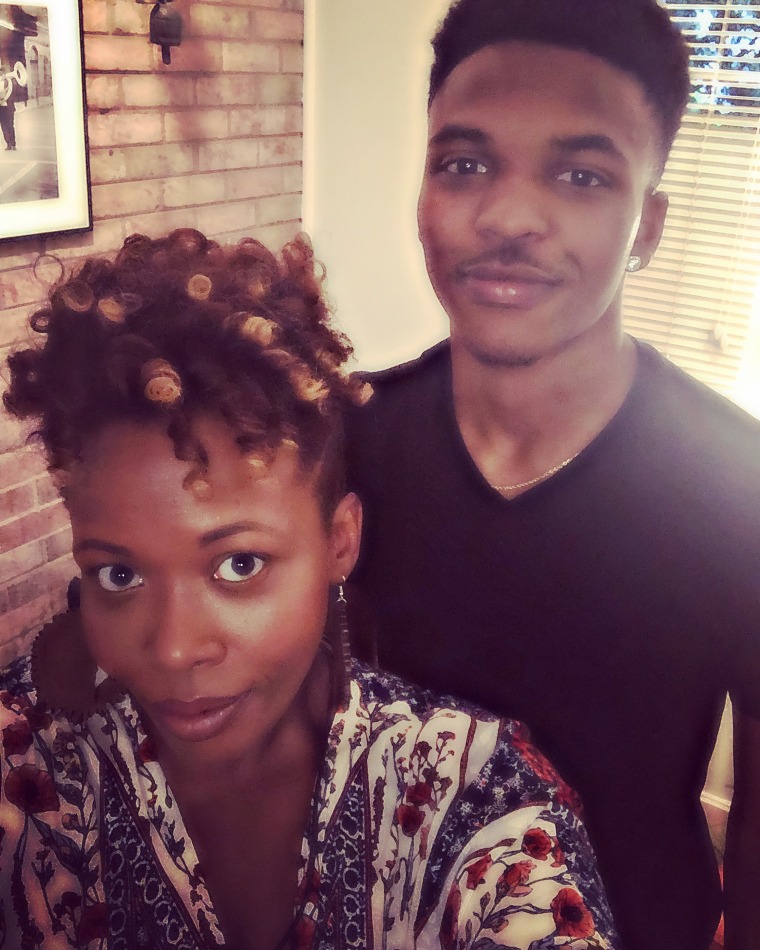

She asked her youngest son, Dorian, then 10, if he might agree to be her bone marrow donor. “I was explaining to him what we would face together when he interrupted me and said, ‘Mom, just stop. I want to do whatever I can to help you.’”

Dorian was a 50 percent match, making him qualified to be his mother’s donor at Johns Hopkins. On transplant day, Whisenton felt hopeful. “I could see me doing things I’d never been able to do.” Plan a vacation. Sit on a beach. Go skiing. All without having to worry about waking up in pain.

It worked.

Improving the Success Rate

But the partial-match transplant does not work for everyone. Of 55 patients who have gone through the procedure at Johns Hopkins, just 37 no longer have evidence of sickle cell disease, according to Dr. Richard Jones, director of the bone marrow transplantation program at Johns Hopkins.

When doctors there tweaked the process, success rates dramatically improved. Eleven of the last 12 cases were successful, Jones said.

Other facilities are using similar techniques, like the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The process is expensive, but it is usually covered by insurers, including Medicare and Medicaid.

Long-term follow-up data will be crucial. Twenty years after the transplant, “I’m willing to call you cured,” said Dr. Alexis Thompson, former president of the American Society of Hematology. “Two years is too short. [But] it doesn’t mean we’re not excited.”

Research presented at a December meeting of the American Society of Hematology suggests that partial-match bone marrow transplants can also help reverse damage done to organs that for years had been starved of oxygen.

In fact, Whisenton says her doctors have told her that her spleen and kidneys — previously damaged by sickle cell disease — are showing signs of improvement.

God Will ‘Finish the Miracle’

Dagny McDonald — a 50 percent match to Jensen — became her son’s bone marrow donor last September. The day before the transplant, Jensen was unable to express any long-term dreams. “I'm thinking everything is gonna be the same,” he said. Jensen could not imagine a life without pain.

Four months later, Jensen is back home in North Carolina. His recovery has not been easy. He’s had to endure additional rounds of chemotherapy. He missed being home for the holidays. Doctors are not yet ready to declare him “cured.”

But his pain? Nearly gone. And so far, no more blood transfusions. The McDonalds have faith. “God will take over and finish the miracle,” said Hans McDonald, Jensen’s father.

“Everything that we dreamed and hoped for when he was born is going to begin.”