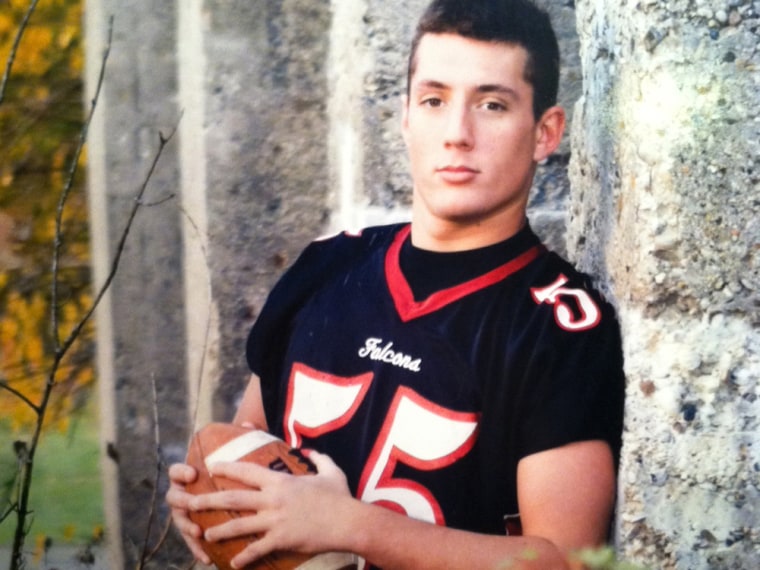

Cody Lehe was still having headaches sustained from a concussion several days earlier at a high school football game. But when his CT scan came back normal, the 17-year-old figured it was OK to play.

Five days after the helmet-to-helmet collision that the Brookston, Ind., teen described as "the hardest I've been hit in my whole life," he was back on the field practicing with his teammates. The Frontier High School Falcons were heading for the 2006 sectional finals and, as team captain, Lehe was determined to be there.

But in the fourth drill of the day, Lehe was hit once again and knocked to the ground. As he slowly pulled himself back onto his feet, the teen told a teammate that his head hurt, but he was OK.

Several plays later, though, Lehe dropped to one knee, dizzy, his legs numb. Then he collapsed, his body shaking with seizures.

He was rushed to the emergency room, where doctors discovered that the pressure in his brain was dangerously high. They reduced the pressure, but the damage was already done.

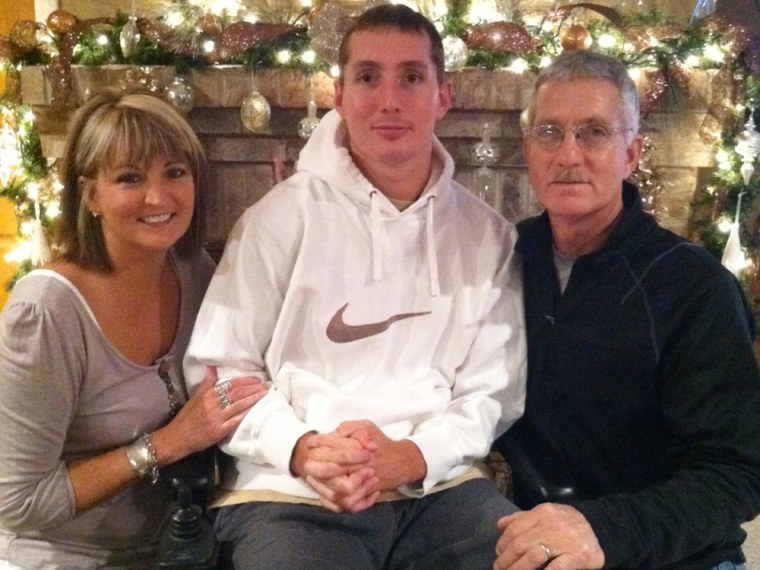

Six years later, Cody Lehe, now 23, cannot walk unassisted and gets around most of the time in a wheelchair. His short-term memory is shot. His plans for college have been put on hold -- perhaps forever.

Lehe is one of the latest victims of a rare injury known as “second-impact syndrome,” or SIS, which can occur when an athlete suffers a jolt to the head too soon after an earlier concussion. Experts say that if the brain doesn’t have enough time to recover from the initial concussion, a second one can have a devastating, often fatal, effect -- even when the second jolt is no more than a light bump.

The second hit causes the brain to swell catastrophically, but it’s the first injury, experts say, that makes the player a walking time bomb.

There have been many reports of second-impact syndrome over the past few decades. But what made Lehe the focus of a new case study, published in the latest issue of the Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, is that the teen had a CT scan after the first hit -- and it came back clean.

“The thing that pushed us to publish this case report was the imaging we had,” says Dr. Michael Turner a neurosurgeon at Goodman Campbell Brain and Spine, a center at the Indiana School of Medicine.

“The most important thing here is that a normal CT scan does not clear you for contact," added Turner, who worked on the study. He hopes the paper will draw the public’s attention once again to the dangers of returning to play too soon.

Experts estimate that more than a million and a half boys play football in U.S. secondary schools and three million play in organized youth leagues each year. Many players get concussions, but nobody knows the true number because players often dismiss head injuries as "dings" and "bell-ringers."

Second-impact syndrome appears to be relatively rare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documented 17 deaths from the condition between 1992 and 1995 in a report that cautioned that those figures could be an underestimate.

A 2007 study in the American Journal of Sports Medicine found 94 incidents of severe football head injuries in high school and college players reported from 1989 through 2002. Nearly 60 percent of the players had a history of previous head injury and more than 70 percent occurred in the same season as the catastrophic injury, the report found. Nine percent of those players died and more than 50 percent suffered permanent neurological injuries.

Although SIS is rare, it is always devastating. Victims who don’t die are left with life-altering brain injuries.

Until Cody’s catastrophic injury, the Lehe family had never heard of second-impact syndrome. They weren’t even convinced that the teen actually had a concussion after the initial helmet-to-helmet hit. Back then, many parents and coaches believed that the signs of a “true” concussion included losing consciousness, blurred vision and vomiting, recalled Cody’s mom, Becky Lehe. Cody had none of those symptoms.

Although Cody was still having excruciating headaches, that clear CT scan gave the teen and his family a false sense of security. And Cody desperately wanted to play.

“He said, ‘I’ve had (headaches) before,” Becky Lehe says. “And if my CT scan says I’m OK, I’m going to keep playing.”

The new case study offers an important piece of information, says Dr. Robert Harbaugh, the researcher who co-authored the Journal of the American Medical Association paper back in 1984 that described second-impact syndrome -- and gave it its name.

“One of the things we postulated back in 1984 was that since athletes so often deny symptoms, including headache, it might make sense to have some type of brain imaging before they could go back to play,” says Harbaugh, a professor and director of the Institute for Neurosciences at Penn State University. “This says that even if imaging was done, it wouldn’t make any difference.”

Parents and athletes -- especially young ones -- need to take every jolt to the head seriously, says David Hovda, a professor of neurosurgery and molecular and medical pharmacology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center.

Every reported case of second-impact syndrome has occurred in young people, Hovda says. And that’s because young brains are still maturing. And one of the big differences between the growing brain and a mature one is that it doesn’t have much room to accommodate swelling. So while an NFL player’s brain can survive some swelling without catastrophic consequences, young brains sometimes can’t.

One of the theories that might explain what happens in second-impact syndrome involves swollen blood vessels, Hovda says. The idea is that after the second hit, the blood vessel walls become less stiff. So, they expand, like a garden hose that becomes fatter as it ages. If enough blood vessels swell, it makes the brain bigger, squashing tissue up against the skull.

So does that mean kids shouldn’t play contact sports? No, says Hovda.

“I’d tell parents to allow their children to play sports, even sports that have contact,” Hovda says. “But be aware that as in any activity there are risks, and the risks of concussion in contact sports are higher than in others.

“When the signs and symptoms of concussion are evident, great caution should be employed before making a decision to return to play. And this decision should be made by a physician who is not affiliated with the team or the school and who has training in concussion management.”

That’s a message that Becky Lehe hopes will resonate with parents reading about her son.

“Cody’s life was spared,” she says. “And we think that part of the reason was so that he could help prevent someone from dying.”

Related stories: