Over the weekend, the 6,000 or so residents of Dayton, Tenn., put on a play, the same play they have put on every year about this time. It retells the story that put Dayton on the map 80 years ago.

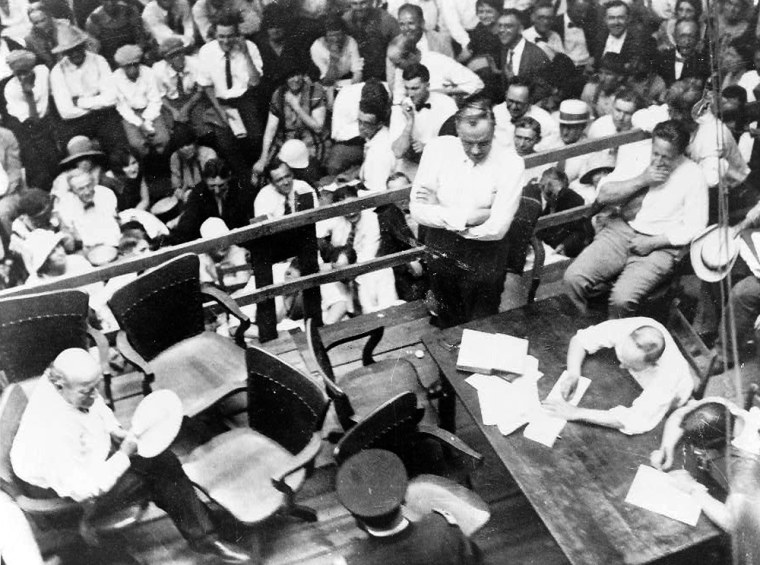

Townsfolk prominent and not so prominent dressed up in the styles of the Roaring ’20s and assembled outside the Rhea County Courthouse to recite the proceedings of the real Trial of the Century: the prosecution in 1925 of John T. Scopes for teaching his students the theory of evolution.

It is perhaps curious that Dayton would do such a thing; after all, the town didn’t come off all that well in the wake of the trial, which ended with Scopes’ guilty plea.

It was the first trial to be covered with the full arsenal of modern media — broadcast live on the radio, filmed for newsreels in the theaters, chronicled by hundreds of newspapers that printed the daily transcript.

The picture that emerged, especially in the hyperventilating prose of the iconoclastic Baltimore journalist H.L. Mencken and later in the play and movie “Inherit the Wind,” was of a town full of “Christian pro-creation” believers who were “uneducated, dimwitted people who came to town barefoot and married their cousin,” said historian John Perry, co-author of a new book, “Monkey Business: The True Story of the Scopes Trial.” He and co-author Marvin Olasky recount the trial and argue for teaching the hypothesis that an intelligent designer shaped the course of human development.

That caricature, like so much we think we remember about the famous Monkey Trial, was largely wrong. And because history has a way of repeating itself — witness recent debates over whether to teach intelligent design in the schools — it is worthwhile to look back at what really happened 80 years ago.

“Why do people still debate the meaning of life or is there a God or not a God?” asked Olasky, a journalism professor at the University of Texas and editor of the Christian-themed newsweekly World. “These are basic, fundamental questions.

“We are, as human beings, the one species that actually can contemplate its own death, and that changes everything,” he said. “The whole question of where we came from, I think, is so fundamental that I don’t think it’s ever going to go away.”

For Dayton, a shot at fame

The most important thing to understand about the Scopes trial was that it was a publicity stunt. There were no fundamentalist preachers trolling the hallways of Dayton’s schools hunting for teachers who were violating Tennessee’s prohibition on teaching evolution.

“By Southern standards, Dayton was relatively progressive,” said Douglas Linder, a professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City law school who maintains the exhaustively detailed Famous Trials Web site, from which some of this account is adapted. “Evolution had been taught in the classroom for a couple of years without any controversy.”

The American Civil Liberties Union had published an offer to defend anyone willing to challenge the statute, and Scopes, a football coach and substitute teacher at Rhea County High School, volunteered at the behest of prominent Dayton residents who thought a show trial would be a good way to get attention.

Clarence Darrow, the most acclaimed criminal defense lawyer in America and a famous skeptic when it came to religious matters, volunteered to help defend Scopes. The prosecution brought in equally impressive firepower: William Jennings Bryan, the champion of progressivism and a renowned orator whom the Democrats nominated three times for president.

For more than a week, Darrow and Bryan sparred over the Bible, Charles Darwin and academic freedom. Or, at least, they tried to. State Circuit Judge John T. Raulston more or less kept the trial focused on the legal matter at hand and eventually barred Scopes’ scientific expert witnesses from testifying on the validity of evolution — it was immaterial to the question of whether Scopes had violated the statute.

“I don’t think many lawyers would really disagree with that conclusion, that as a matter of law he was probably right about that,” Linder said. But its effect was to drain the trial of much of its attraction: the titanic confrontation between Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan over God, life, the universe and everything.

So Darrow decided late in the trial to call an expert on the Bible. He called Bryan. And that was where what had already been a media sensation turned into a circus.

The other prosecutors tried to object, but Bryan, a fervent fundamentalist who saw his participation in the trial as a righteous act, waved them off, saying he had nothing to fear. “I have studied the Bible for about 50 years,” he declared.

Bryan: Zealot or victim of libel?

If you read only Mencken’s account, dripping with big-city Northern snobbery, or remember Fredric March’s semi-hysterical performance as the fictionalized Bryan in “Inherit the Wind,” you could be forgiven for believing Darrow demolished Bryan and, with him, the biblical account of creation. But the trial transcript and more objective contemporary coverage tell a different tale.

The popular story is that Bryan, overwhelmed by Darrow, took recourse in reciting Bible verses before collapsing on the stand and dying shortly thereafter, a broken man. In fact, the trial transcript shows that Bryan gave as good as he got. Far from blindly retreating to fundamentalist literalism, he allowed that much of the Bible was allegory, testifying that the six days of creation could have been metaphorical periods. “I do not think they were 24-hour days,” he said.

And far from being shattered when Raulston finally called a halt to his testimony, Bryan was eager to keep going:

Bryan: The only purpose Mr. Darrow has is to slur at the Bible, but I will answer his questions. I will answer it all at once, and I have no objection in the world. I want the world to know that this man, who does not believe in a God, is trying to use a court in Tennessee to slur at it, and, while it require time, I am willing to take it.

The defense pleaded guilty the next day, largely so it could go ahead with its appeal — Scopes’ conviction and $100 fine were overturned on a technicality two years later — but motivated partly, Darrow said later, by fear of the closing statement Bryan planned to make.

Bryan was invigorated by his side’s legal victory. He was making speeches and working on publishing his closing statement when he died five days later. An untreated diabetic, he passed away quietly during his afternoon nap after a heavy lunch.

“Bryan has really gotten a bad rap. A man who was kind of the great progressive politician of his era has gone down in history as a narrow-minded bigot and a religious zealot,” said Jeffrey P. Moran, an associate professor of history at the University of Kansas and author of the 2002 book “The Scopes Trial: A Brief History with Documents.”

“Historians know better. They know he was very instrumental in getting direct election of senators, in helping with women’s suffrage and for doing all sorts of good things,” Moran said. “But it’s sort of like gymnastics. Judges rate you on what you did last, and Bryan didn’t really stick the landing.”

Historians agree that Darrow came off a lot better. Mencken, after all, recommended him for the job, and the authors of “Inherit the Wind” — which they said was actually an allegory about Sen. Joseph McCarthy and the communist witch hunt of the 1950s — saw in him a spokesman for open inquiry and tolerance.

As for Dayton, scholars on all sides say it got blindsided. The trial generated publicity beyond the wildest dreams of the town’s leaders, but not necessarily the sort they were seeking. It was “extremely successful” in putting Dayton on the map, Perry said, but it was no great economic boon.

“So on one hand the publicity was terrific, but on another it was unfair. It sort of stamped these people as these hillbilly hicks who drank moonshine and came into the town with shotguns over their shoulders,” he said. “I suppose it depends on how you look at the question, whether it was successful.”

Assessing the fundamental impact

More damaging, perhaps, is the stereotype of fundamentalist Christians that has survived since the trial.

“The general idea we have of the Scopes trial is that it was largely a kind of rural Southern phenomenon. That’s really caused trouble for people trying to understand the anti-evolution movement: From Scopes we got this idea that it was simply yahoos in overalls who didn’t like book-learnin’,” Moran said. “What’s happened in the last 40 years is creationism has become quite suburban, even quite well-educated and not purely a Southern phenomenon.”

At the same time, he said, debate today may be stifled by civic leaders afraid of the fallout in Dayton.

“What you hear now is cities are kind of terrified about what a new Scopes trial is going do to their reputation,” Moran said. “They remember the original ended up besmirching the name of Dayton, Tennessee, and making it a synonym for bigotry and ignorance for the rest of the century.”