They invoke the names of Martin Luther King Jr. and Cesar Chavez, but the hundreds of thousands of immigrants who have marched nationwide are not following one charismatic leader.

Instead, they’re loosely guided by Hispanic advocacy groups, churches and labor unions — organizations that have helped transform isolated campaigns in major cities into a broad movement with a coordinated strategy.

“There is no one leader, and that’s a good thing,” said Nativo Lopez, president of the Mexican-American Political Association, a central organizer of rallies in Southern California. “It’s a shared leadership among people who we don’t even always know.”

What began with a national organizational meeting just two months ago has resulted in unions blanketing workers with fliers at hotels, restaurants and stores, Roman Catholic churches accelerating their campaign of preaching to immigrants and pressuring politicians, and Hispanic community leaders working with radio deejays to give protesters detailed instructions: wear white, remain peaceful and be positive. And when marchers were criticized for carrying Mexican flags, organizers quickly spread the word to carry U.S. flags instead.

If any one person deserves credit, organizers say, it’s a man who surely didn’t seek the distinction: Rep. James Sensenbrenner, a Republican from Wisconsin.

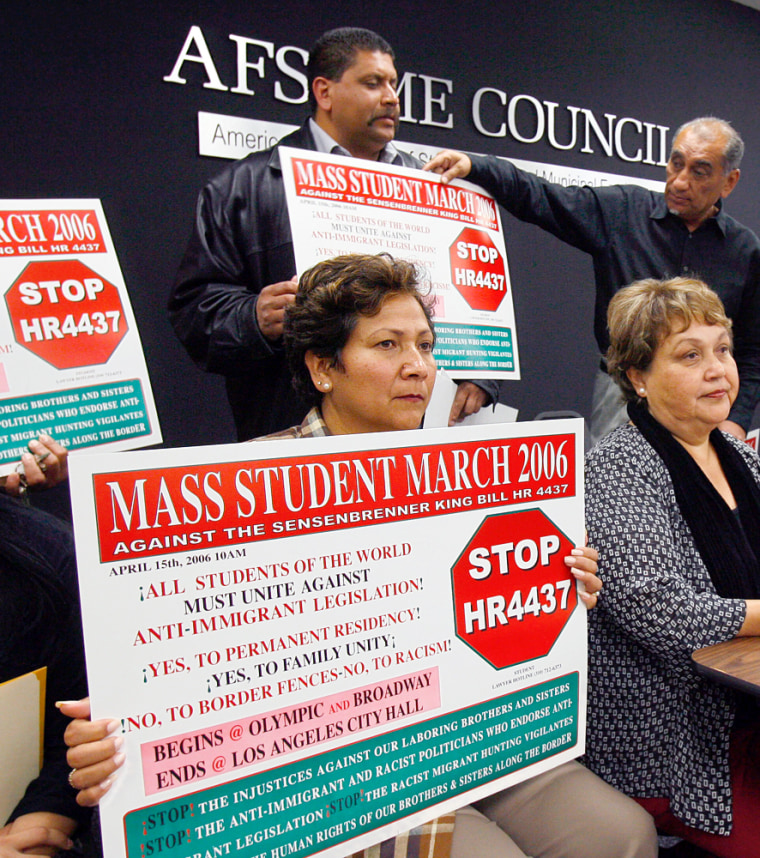

Sensenbrenner sponsored legislation the House passed in December that would make being in the country illegally a felony, criminalize people who help illegal immigrants and build a 700-mile fence along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Groundswell of anger, activism

The bill provoked a groundswell of anger in immigrant communities, and many groups nationwide immediately began small protests in Chicago, Phoenix and Los Angeles. But those efforts were largely local and didn’t have a guiding vision.

That led a handful of civil rights groups in Southern California to convene a hastily arranged one-day national summit Feb. 11. About 500 people from unions, civil rights groups and religious organizations from around the country jammed a large room at the Riverside Convention Center.

Hundreds of e-mails between the groups led up to the meeting, and they set the stage for what began as an unfocused jumble of competing agendas.

“For about the first 30 minutes it was chaotic with everybody raising their hands and speaking,” said Armando Navarro, coordinator of the National Alliance for Human Rights, an umbrella organization for Hispanic activist groups in Southern California. “Then we got on track.”

Organizers said they set aside fundamental divisions over whether illegal immigrants should be allowed to stay or given guest worker status and agreed on a series of mass mobilizations through April 1, in anticipation of the Senate taking up its own immigration reform legislation. The protest themes would be twofold: Opposition to the Sensenbrenner legislation and a call to give the estimated 11 million illegal immigrants the right to live in the U.S.

“I got the feeling like this was the beginning of a national movement,” said Angela Sanbrano, executive director of Carecen, a Hispanic civil rights group in Los Angeles. “Everybody was talking about what they were going to do when they got back.”

In addition to Spanish-language radio, much of the word was spread through e-mail, Web sites and cell phones.

Flexing political muscle

The first day Riverside attendees targeted was March 10. While organizers in major cities such as Los Angeles weren’t able to launch a protest, about 100,000 marched in Chicago. Two weeks later, about 500,000 protested in Los Angeles.

By then, the Catholic Church and the Service Employees International Union were flexing their organizing muscle.

Kevin Appleby, director of migration and refugee policy for U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, said many dioceses gave out fliers advertising the rallies at Sunday Mass or at other church events. Well before the any demonstrations had been planned, the bishops’ conference had distributed parish “kits” nationwide to help clergy educate Catholics about immigration, including homily notes, bulletin inserts and other material.

Hundreds of SEIU members have helped control crowds at California rallies. Ahead of Monday’s march in Phoenix, the union’s Washington, D.C., headquarters received a call from organizers who were having trouble getting a permit because of insurance issues.

“So we called around. We found a policy. We wrote a check,” said Ben Boyd, a union spokesman.

He said SEIU leaders quickly realized that if the protests turn into a movement, it could indirectly benefit the union’s efforts to organize and recruit potential members.

“Does it help when we cater to service workers and a growing number of those jobs are taken by immigrants coming into the cities? Yes. That something we know all too well,” Boyd said.

The planning is far from over.

Organizers promise major voter registration drives and are promoting May 1 as a day on which immigrants are asked stay home from work and school, and refrain from buying U.S. products.

“It’s great,” said Magdalena Schwartz of Immigrants Without Borders in Phoenix, “because we see now we are not alone.”