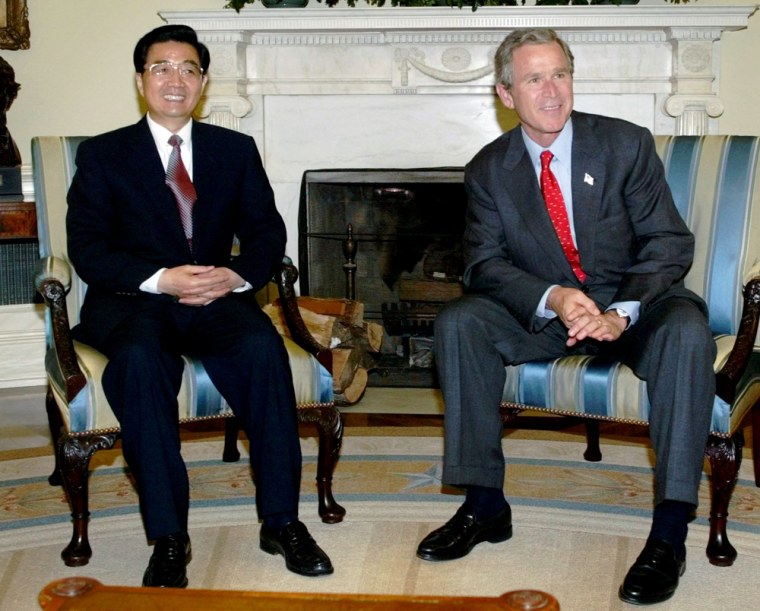

When Hu Jintao made his first visit to Washington, the then-vice president of China never deviated from the official policy line, leaving Bush administration officials perplexed as to what kind of leader he would become.

Four years later, Hu arrived n the United States on Tuesday with an answer to that question: He is president and undisputed leader of a fast-rising nation whose emergence poses economic, diplomatic and security challenges for Washington.

A telegenic but uncharismatic technocrat, Hu has presided over an impressive run-up in Chinese power, striking a populist tone and squelching dissent at home while pursuing free-market policies and broadening the country’s contacts abroad.

The result has been to make China and the Communist Party a greater force to be reckoned with than many supposed when he was named party chief in late 2002. “Hu Jintao has taken the Communist Party’s power and linked it with capitalism to bolster one-party rule,” said Ruan Ming, a former Propaganda Department official.

“Look, one of the first things he’s doing when he gets to America is having dinner with a hundred businessmen at Bill Gates’ home,” said Ruan, an author who now lives in Taiwan.

Seattle, D.C. and Yale

Hu has set an ambitious mission for his four-day U.S. tour. His trip comes at a time of unease among American businesses, political leaders and the public about how China is using its new power.

His summit Thursday with President Bush will cover a broad agenda — from China’s much criticized currency and other trade policies, to its aggressive search for oil and Iran’s and North Korea’s nuclear programs.

The real test lies beyond the White House. In addresses and meetings, Hu hopes to dispel skepticism about Chinese intentions among key audiences: business leaders in Seattle, where he’ll tour Boeing and Microsoft facilities, the policy-making establishment in Washington and the academic elite at Yale University.

The foray into public diplomacy is uncharacteristic for Hu, who as a party insider for two decades has excelled in closed-door politics. It’s remarkably different from his first trip to Washington, in May 2002, when he stuck to private meetings and kept to the line set by Beijing.

“No matter the situation, Hu never gives offense,” said Wu Jiaxiang, a former researcher in a high-level party office and an occasional political commentator.

Policy wonk, not karaoke singer

At age 63, Hu remains a puzzle to ordinary Chinese and to foreign leaders. Said to possess a photographic memory, he impressively discusses policy without briefing papers. But Hu eschews the limelight and the personal give-and-take that delighted his predecessor, Jiang Zemin, who once tried to get Queen Elizabeth II to sing karaoke.

At home, Hu’s public appearances are rare and kept to tightly scripted meetings with farmers and others. The only high-level news conference of the year is conducted by his premier.

Hu has engineered a distinctive shift in Chinese policies that sets him apart from Jiang. Internationally, Hu has steered China away from Jiang’s U.S.-centered foreign policy.

On the back of an economy that is heading into its fourth year of 10 percent growth and has become the world’s third-largest trader, Hu has won over Southeast Asian neighbors with trade, raised Chinese investment and presence in Africa and Latin America and gained access to oil from strategically shaky Central Asia and the Middle East.

Revenues from the robust economy have allowed him to divert resources to struggling farmers and unemployed urban laborers. He has issued a vaguely Maoist appeal for clean living by party members and called for “a harmonious society” — seeking to deflect popular anger over income disparities and land seizures onto local officials and away from the top leaders in Beijing.

“These policies make people think that there’s hope,” said Wu, the former party researcher.

Grew up in poor areas

Hu’s emphasis on the downtrodden, especially in rural China, bespeaks his formative years. The son of a struggling tea merchant, Hu spent a decade working on a dam and in a construction bureau in Gansu, one of China’s poorest provinces. In the 1980s, he was dispatched to run Guizhou and Tibet, chronically impoverished regions.

The switch to a more populist line has brought Hu political benefits. Many of Jiang’s allies in the current government rose to power in economically more prosperous areas and have seen their influence diminished by the shift, Ruan and others said.

Even as No. 1 leader, Hu treads carefully. Mistakes in the U.S. could prompt criticism and derail his chances to be given a second term as party chief at a conclave in 2007.

“He won’t really emerge as his own leader until the next party congress,” said Jin Canrong, an America watcher at Renmin University.