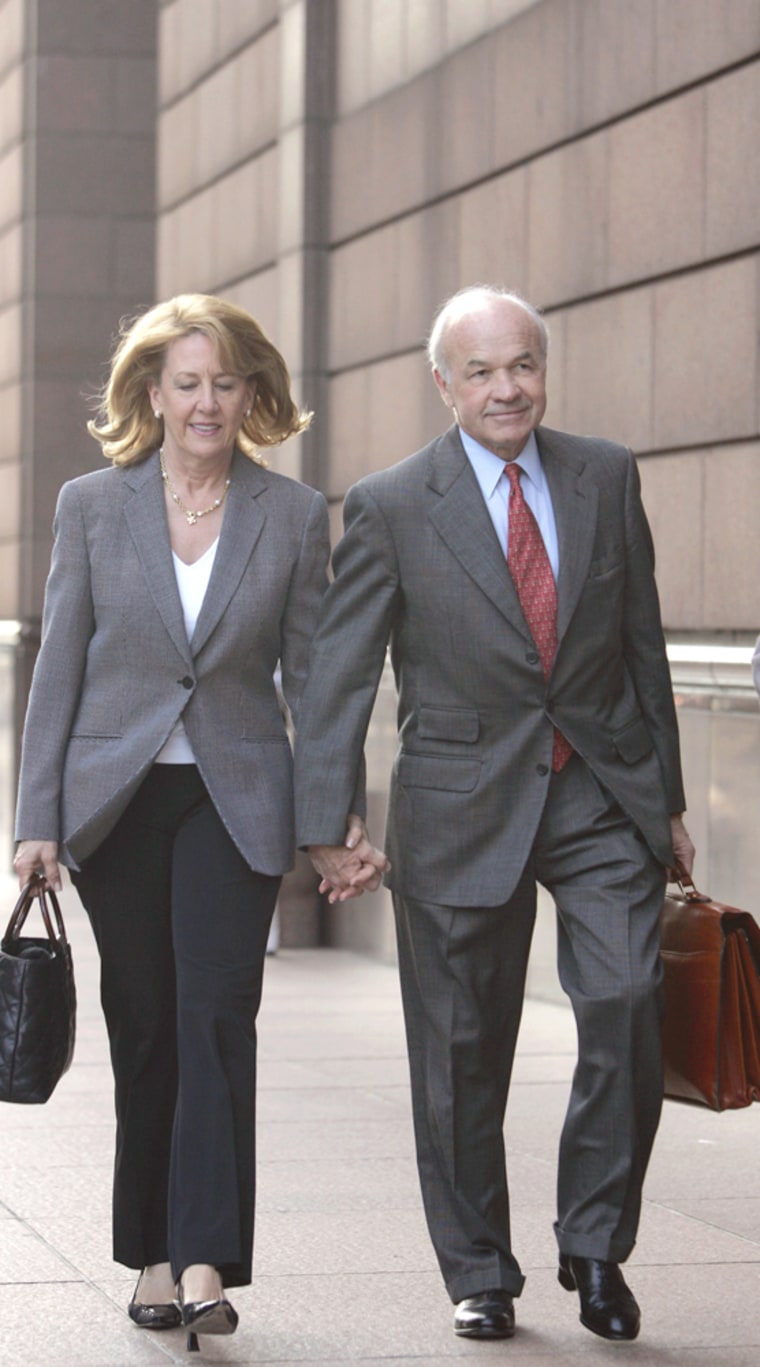

Enron Corp. founder Kenneth Lay said Tuesday he doesn’t remember being told about any rules governing the use of loan money by banks to buy stock, and insists that while he’s responsible for the error, he never intended to break the law.

“I don’t recall them ever coming to my attention we were not in compliance with any of those loan agreements,” Lay said. “I can’t categorically say somebody didn’t, but I sure can’t recall.”

Lay said even though he received periodic reports about the loans, he didn’t really read the entire documents and focused primarily on the remaining balances “to have something in my head.”

He denied trying to be deceptive.

“It was not part of my consciousness at that time,” he said.

U.S. District Judge Sim Lake, who is hearing the case without a jury, anticipated closing arguments early Tuesday afternoon. But Lake will not release his verdict in the case until a jury finishes its deliberations in the main fraud and conspiracy case involving Lay and former Enron Chief Executive Jeffrey Skilling.

The jury in that case, where Lay faces six charges and Skilling 28, including insider trading, was deliberating Tuesday for a fourth day.

Lay, who has yet to be cross-examined in the bank fraud case, acknowledged that he clearly wasn’t in compliance in different investments and different paybacks.

“Ultimately, it’s my responsibility,” he said Monday. “I regret I did not have more time to spend on my personal matters and perhaps this is one of the consequences of that.”

Prosecutors allege that beginning in 1999, Lay obtained $75 million in loans from three banks — Bank of America, Chase Bank of Texas and Compass Bank — and then reneged on an agreement with the lenders that he wouldn’t use the money to carry or buy stock or mutual funds. The federal rules governing use of loans for stock sales were covered in documents Lay signed.

He was indicted in 2004 on one charge of bank fraud and three charges of making false statements on loan documents.

His personal banker testified earlier the rules were spelled out to Lay.

Lay said he didn’t remember ever hearing a discussion in his years as director of several banks.

He said he didn’t dispute using the money to buy stock, but he added he had no intention to defraud the banks or make false statements.

“I did not nor would I have if I knew what the facts were,” he said.

He said documents for his signature routinely were handed to him by his assistants and after reviews by lawyers who he believed “were doing in good faith and doing the best job they could with the information they had.”

Lay’s personal accountant also testified on Monday she was unaware when she transferred money from loans Lay had obtained that federal regulations barred use of some of the money for stock purchases.

Sherrie Gibson, contradicting her own grand jury testimony, said sometimes she decided herself which of Lay’s multiple lines of credit to use but didn’t intend to be deceptive.

“I never think in terms of sneaky,” she said.

Gibson also said Lay never told her to circumvent any regulations.

The final government witness was FBI agent Robert Cunnane, who specializes in white-collar fraud and who reviewed thousands of documents related to Lay’s loans and stock purchases. Cunnane said Lay’s statements that he wouldn’t use the money to buy stocks were untrue.

But under cross-examination, he said he found no documents where any agency or bank raised concerns regarding any of the transactions.

Conviction on each of the four charges carries up to a 30-year prison term.

Lay’s lawyers last week questioned the legitimacy of the bank documents containing the loan terms by suggesting the loan agreements actually were signed by an automatic signature device in Lay’s office and not by him. On Monday, they again objected to some documents allowed into evidence that carried his signatures.

But Lay, in his testimony, said he was “a little upset” that “so much was made over it.”

While acknowledging he didn’t read everything he signed or what the machine signed, “Certainly, it was an authorized legal signature.”

The counts against Lay were part of the main fraud and conspiracy case against the Enron founder and Skilling. But Lake, ruling in October 2004 on a request by Lay to have his case heard separately, agreed only that the four banking counts would be heard alone.