The Middle Ages met the Internet age Friday when the Domesday Book — a survey of England conducted almost 1,000 years ago — went online.

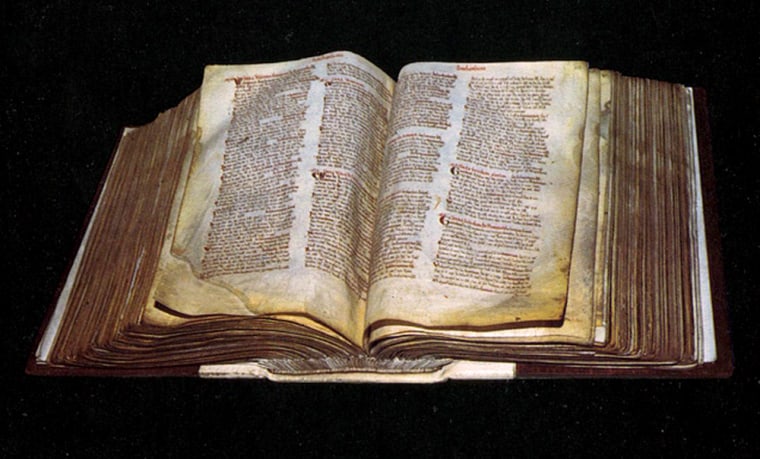

The book, a record of the people and lands ruled by William the Conqueror, is the oldest record held by Britain’s National Archives and one of the country’s most valuable documents. Now anyone with an Internet connection can, for a fee, download copies of handwritten records that provide a picture of life in the 11th century.

“It is important that people of all ages should be able to read and use this national treasure,” said Adrian Ailes, a Domesday expert at the National Archives, which in the past few years has placed millions of historical documents — from World War I records to 1960s public information films — on the Net.

The Domesday Book was compiled on the orders of William I, who became England’s king when he defeated the Saxon king, Harold, at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1085, he ordered a survey to determine the taxable value of his kingdom.

Officials fanned out across England to assess who owned the land and what was on it. The result is a detailed record that lists more than 13,000 places. Farmland, woodland, meadows, pastures, mills and fisheries are enumerated; there are estimates of the number of freemen, indentured peasants and slaves on each estate.

Places have changed

Many place names listed in the book are still recognizable, although the places themselves have been transformed. Holborn, now a central business district of London, was Holeburne, home to peasants and a vineyard. Islington — now a busy commercial and residential area of north London — was the rural settlement of Iseldone.

Kensington — now one of London’s wealthiest areas — had “meadow for two ploughs, pasture for the livestock ... woodland for 200 pigs and three arpents of vineyard.”

“I think people warm to the Domesday Book and its specific contents because it contains 13,418 place names,” said Ailes. “Everyone is related in some way to this piece of history. It is very tangible.”

The Web site allows surfers to search by place or a person’s name. Summaries of the records are free, but the pages themselves — along with a translation from the original Latin — are $6.60 each.

The National Archives warned that people hoping to trace their ancestors might be out of luck: Only landowners are listed by name; the majority of 11th-century Britons remain anonymous.

Well-known, little-understood document

The book consists of two parchment volumes: Little Domesday, which covers part of eastern England; and Great Domesday, which includes much of the rest of England and the Welsh borders. Scotland and parts of northern England that remained outside William’s control were not included.

The book’s name is thought to come from Doomsday, the biblical day of judgment — a reference to its authority.

It depicts a highly structured feudal society, in which the royal family and a handful of barons owned 40 percent of the land. Most people were either freemen; semi-free peasants called sokemen; indentured peasants known as villans or cottagers; or slaves.

The book is one of Britain’s best-known documents, but a poll commissioned by the National Archives suggests not everyone is sure what it is. While 80 percent of respondents had heard of the Domesday Book, 13 percent thought it was a chapter in the Bible — and 2 percent thought it was a book by Dan Brown, author of the hugely popular “The Da Vinci Code.”

NEMS Market Research interviewed 500 people between May 25 and 30 for the poll. No margin of error was given.

The Domesday Web site is at .