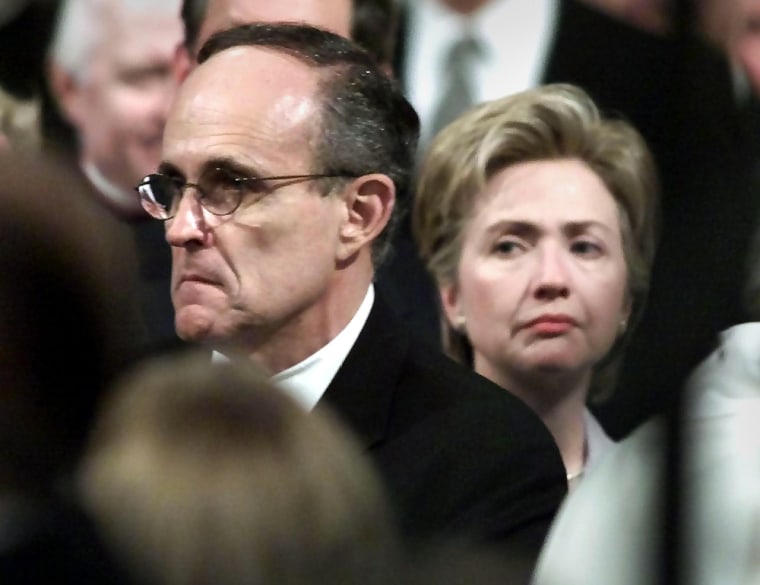

By the time Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani of New York stepped before a wall of television crews in the Public Hearing Room at City Hall on May 19, 2000, there were no surprises left.

In the course of three tumultuous weeks, Mr. Giuliani had been told by doctors that he had prostate cancer. He had announced he was leaving his wife after tabloids reported he was having an affair. And now, he had come to withdraw from the Senate race against Hillary Rodham Clinton, bringing a sudden end to what was arguably the most anticipated Senate campaign of modern times.

But the 12 months leading to Mr. Giuliani’s departure are as instructive today as they were riveting then: a blistering year of mental gamesmanship, piercing attacks, contrasts in personalities and positions, and blunders, played out by two outsize political figures in a super-heated atmosphere.

It was a year in which both Mr. Giuliani and Mrs. Clinton gained many of the political skills the nation is seeing now as they campaign for president. It was a time in which they took a measure of one another as opponents. And it was a shared chapter in their lives that offers a window into what a 2008 White House contest between these New Yorkers might be like, should they each win their party’s nomination.

On the morning when Mr. Giuliani quit, the two sides were deep into preparing for a fall campaign. After an uncertain start in which Mr. Giuliani kept her off balance, Mrs. Clinton had found her way to handle the gibes thrown at her by the confrontational mayor. Rather than engage him, Mrs. Clinton became the foot-tapping, arms-folded sighing mother of a forever misbehaving teenager, a mien intended as much to infantilize Mr. Giuliani as to provoke him.

“I can’t be responding every time the mayor gets angry,” Mrs. Clinton said, smiling as she campaigned in upstate New York a few days before Christmas 1999. “Because that’s all I would do.”

Both sides were prepared for the battle. Television advertising scripts had been drafted (“She says she is a Yankee fan, but she hasn’t even been to a Yankee game,” was the tag line of one Giuliani advertisement), vulnerabilities had been identified and campaign themes tested. Mr. Giuliani’s aides had prepared an indexed 315-page dossier compiling positions and potentially damaging quotes from throughout her life, according to people who saw it. (It included an 11-page chronicle titled “Stupid Actions and Remarks.”)

Mr. Giuliani was going to portray Mrs. Clinton as inauthentic, inexperienced, a liberal champion of big government and a carpetbagger, his advisers said in interviews. Mrs. Clinton was going to paint Mr. Giuliani as divisive and undignified, temperamentally unsuited for the Senate, and profoundly uninterested in national and international affairs, her advisers said.

More than anything, the early stages of the 2000 Senate race offered a lesson on the politics of psychological warfare, as each campaign sought, in the words of one Clinton adviser, to “get inside the head” of the other’s candidate.

Mr. Giuliani pounced on Mrs. Clinton’s slightest misstep, sensing vulnerability in this new and nervous candidate. The mayor, a former prosecutor, often exaggerated her misdeeds and slightly mischaracterized her positions, aides said, in a deliberate effort to goad her into correcting his version of her record — while Mr. Giuliani skipped on to his next attack. He was brash and theatrical, flying to Little Rock one day to announce that he would fly the Arkansas flag over City Hall in New York to highlight the fact that Mrs. Clinton was running for office in a state where she had never lived.

In announcing his withdrawal from the race to succeed Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Democrat, Mr. Giuliani said he wanted to turn his attention to fighting his cancer. But some of his aides and senior Washington Republicans say today they had concluded weeks before that he had lost interest in the race, in part because he had become enamored of Judith Nathan, the woman with whom he was having an affair, but also because he realized that he was drawn to the campaign more by the sport and distinction that would come with beating a Clinton than he was by the prospect of serving in the Senate.

As the spring came, Mr. Giuliani would joke gloomily, over cigars, about life as a junior senator and the transition of going from chief executive to one of 100 people, one friend said. He complained about the burdens of fund-raising, while his aides grew frustrated at his reluctance to campaign outside of New York City or discuss federal issues.

As their presidential campaigns look to the past in preparation for a possible renewal of their aborted contest, they have reached strikingly similar conclusions about their potential opponent: Eight years older and more experienced, Mr. Giuliani and Mrs. Clinton are each far tougher and more rounded candidates than they were in 2000.

“She is a great candidate now,” said Frank Luntz, who was Mr. Giuliani’s pollster in 2000. “She is a tough-as-nails candidate today. She has learned how to turn people who were openly hostile to her into supporters.”

Anthony V. Carbonetti, one of Mr. Giuliani’s chief political advisers, said Mrs. Clinton’s lack of executive experience was a critical liability with New York voters in 2000, and would be again with national voters.

“But she is a completely different person,” Mr. Carbonetti said. “You have to give her credit for the Senate experience now. She is not the demon now that she was coming out of the White House. I would not underestimate her at all.”

Much the same sentiment is voiced about Mr. Giuliani by Mrs. Clinton’s advisers. “I’m not going to dispute you on this: He seems like a more disciplined candidate now,” said Howard Wolfson, who worked as Mrs. Clinton’s communications director in 2000, where he frequently tangled with Mr. Giuliani, and is serving the same role again. “I am surprised at the way he has kept his anger in check.”

Ready to run

It was the start of 1999, and Mr. Giuliani, like Mrs. Clinton, was approaching a turning point in his career. Term limits prevented him from running a third time for mayor, and his advisers said there was never much debate about what he should do next. He viewed the prospect of running against a Clinton as irresistible.

He instructed two of his top consultants from the 1997 campaign for mayor — Adam Goodman and Rick Wilson — to prepare a comprehensive catalog of her public statements, writings and positions going back to when she was a student at Wellesley, a road map into her foibles and vulnerabilities. (Turn to Page 39 for the Lincoln Bedroom; 139 for Whitewater.)

But Mr. Giuliani was trying to plan his campaign as he was running a city, and often seemed to make little effort to find time for his political advisers. They would hop into Mr. Giuliani’s Suburban as it whisked him around the city, where he would turn from talking about the best way to go after Mrs. Clinton to how to deal with the threat of a transit strike at the end of 1999. Mr. Luntz said Mr. Giuliani would arrive at Gracie Mansion after 10 p.m. for campaign planning meetings.

In these sessions, Mr. Giuliani and his aides concluded that Mrs. Clinton would run a highly ordered, meticulous and policy-driven campaign, make an appeal to women on Long Island, and seek to discredit Mr. Giuliani by identifying him with Washington Republicans.

In Mrs. Clinton, Mr. Giuliani’s aides told the mayor, he was facing a smart, cold and tentative opponent, unprepared for the maelstrom of a New York City campaign. The issue of her residency became more than a way to win tabloid headlines: Mr. Giuliani saw it as a way to underline voter perceptions of her as inauthentic, opportunistic and untrustworthy. When Mrs. Clinton flew to New York from Washington for a parade, Mr. Giuliani welcomed her with sarcasm. “I hope she knows the way,” he said. “I hope she doesn’t get lost on one of the side streets.”

Candidate in training

Mrs. Clinton began that spring with a series of talks with advisers about what she should do now that her husband was leaving the White House. By late spring, the discussion — typically a half-dozen people gathered in the Yellow Oval Room in the second-floor family quarters of the White House — had evolved into a political tutorial on how to be a candidate, how to run in New York and how to deal with Mr. Giuliani.

Her advisers could not have been better suited to the task. Four of them had worked in tough New York campaigns, and two of those had worked in campaigns against Mr. Giuliani. (They remain the nucleus of Mrs. Clinton’s political cabinet today.)

Mandy Grunwald, Mrs. Clinton’s media adviser, was the media consultant to Ruth W. Messinger when she ran unsuccessfully for mayor against Mr. Giuliani in 1997. Mark Penn, who was Mrs. Clinton’s pollster and is today her chief strategist, advised David N. Dinkins when he defeated Mr. Giuliani in the 1989 mayor’s race.

Mr. Wolfson was communications director for Charles E. Schumer when he beat Senator Alfonse M. D’Amato in 1998. Harold Ickes, a longtime close adviser to the Clintons, has been a warrior in New York City politics for 40 years.

This group had observed Mr. Giuliani in three mayoral campaigns, and there was little disagreement about how to run against him: focus on his temperament, his identification with Republican policies and the notion that he was running for a job that did not interest him. Perhaps more significant, when viewed in the context of a potential 2008 rematch, Mrs. Clinton’s advisers suspected that the first lady, who grew up in suburban Chicago, would be a culturally more appealing candidate to rural voters than Mr. Giuliani.

Mrs. Clinton’s advisers reached many of the same conclusions about her weaknesses that Mr. Giuliani’s advisers had.

So it was that Mrs. Clinton began her campaign that summer not in New York or its suburbs, but in rural Republican upstate New York, sitting down with small groups of voters. The ostensible purpose of what was called her listening tour was to defuse the criticism of her residency. But it allowed her to learn how to be a candidate and test her upstate appeal.

Yet her low-profile, make-no-waves campaign style worried New York Democrats as they watched Mr. Giuliani gleefully goad her from City Hall.

Those worries peaked in November, when Mrs. Clinton traveled to the West Bank city of Ramallah and sat silently as Suha Arafat, the wife of the president of the Palestinian Authority, accused Israel of deploying carcinogenic gases to control Arab protesters in Gaza and the West Bank. It took 12 hours before Mrs. Clinton rebuked Mrs. Arafat; by that point, she had been repeatedly assailed by Mr. Giuliani.

In the weeks after her return, Mrs. Clinton and her advisers determined that they could not win the race unless they turned attention away from Mrs. Clinton and on to Mr. Giuliani: to cast him in “the angry frame,” as one described it. At every opportunity, Mrs. Clinton and her advisers suggested that Mr. Giuliani was slightly out of control, a characterization that was intended to raise doubts about Mr. Giuliani and knock him off stride.

And there were signs it was working. Mr. Giuliani suggested he was the victim of a Clinton-directed conspiracy that included pushing the Brooklyn district attorney, a Democrat, to investigate his campaign manager, Bruce Teitelbaum. “You’ve got to be living on Mars not to figure out what’s going on,” Mr. Giuliani said.

As spring arrived, Mr. Giuliani had yet to give a major speech on federal issues. He was barely campaigning upstate. Mr. Giuliani dismissed the concerns of Republican leaders, explaining that he, unlike Mrs. Clinton, had a full-time job.

Mr. Giuliani’s campaign began to falter in March. New York police officers shot and killed an unarmed black man, Patrick Dorismond, after he ran from undercover agents who asked if he had any drugs to sell. Mr. Giuliani authorized the release of Mr. Dorismond’s sealed criminal records from when he was a juvenile and went on Fox News Sunday, where he proclaimed that Mr. Dorismond was “no altar boy.” The remarks ripped across an already polarized city.

Mr. Clinton had already been scheduled to appear the next night at the Bethel A.M.E. Church in Harlem. The church was packed with cameras and reporters as Mrs. Clinton, clasping hands with prominent black leaders, walked in singing “We Shall Overcome,” before delivering a speech accusing Mr. Giuliani of dividing the city.

Mr. Giuliani headed upstate, for a Republican dinner in Binghamton. He spoke for exactly 22 minutes, stood for an eight-minute news conference, and then turned for home. Less than a week later, he abruptly canceled four upstate events because, he said, he wanted to attend the rescheduled opening game of the Yankees.

Mrs. Clinton’s campaign pounced. Overnight, aides arranged a trip for her to the cities Mr. Giuliani had snubbed and worked the telephone with upstate reporters to stoke the story.

The end

By the time Mr. Giuliani stepped in front of the cameras to announce he was dropping out, Republicans had already concluded that the mayor would not stay in the race: indeed, many were praying he would not. His cancer seemed almost beside the point.

Evidence of his lack of interest had been building for months: the erratic campaign schedule, his treatment of upstate voters, the public way he was carrying on his relationship with Ms. Nathan. His poll numbers were sinking (a New York Times/CBS News poll taken after the Dorismond episode found Mrs. Clinton leading the mayor by 10 points statewide), and he had become a punch line on late-night talk shows.

It was a frazzled end for Mr. Giuliani’s aides, concerned about the health of a friend, bewildered by the humiliating political meltdown they were witnessing, and frustrated that all their preparation for this epic battle would be put aside and that Mrs. Clinton would be left with a relatively easy start for her solo political career.

To this day, their aides quarrel over how the race would have ended had Mr. Giuliani not withdrawn. “If he would have stayed in the race, we would have won,” Mr. Penn said. Told of that, Peter Powers, Mr. Giuliani’s longtime political adviser and close friend, responded, “We viewed her as somebody we can easily beat — not easily, but someone we could beat.”

Mr. Giuliani’s advisers said he could have overcome the collapse of his marriage, assuming he was physically well enough to stay in. But they are not sure they could have overcome another obstacle: that Mr. Giuliani was running for a job that he did not seem to want.

Should their status as their parties’ national front-runners bear up under the actual voting in the primaries, Mr. Giuliani could get the fight against Mrs. Clinton he has been spoiling for. And this time, it is for a job that he by all appearances covets. That may well be the most significant difference between the Clinton-Giuliani race that almost was and that Clinton-Giuliani race that could now be about to unfold.