The end seems to have finally come for NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander mission at the planet's north pole, scientists said Monday.

"At this time we're pretty convinced that the vehicle is no longer available for us to use," said the Phoenix mission's project manager, Barry Goldstein of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

"We knew this would happen eventually," Goldstein added.

Mission controllers lost touch with the lander on Nov. 2. That was "the last time we actually heard from Phoenix," Goldstein said. The spacecraft has been studying the arctic surface of the Red Planet for just over five months, since landing there May 25.

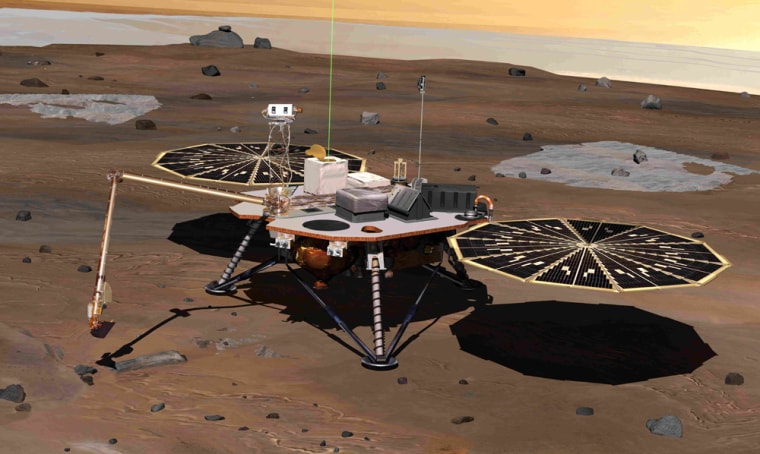

During the course of its mission, Phoenix scooped up samples of the Martian dirt and subsurface water ice at its arctic landing site and analyzed them for signs of the planet's past potential habitability. Phoenix touched down on the northern plains of a region known as Vastitas Borealis. The area is at a latitude on Mars equivalent to that of northern Alaska on Earth.

Phoenix successfully completed its mission objectives at the end of its three-month primary mission in August. The mission's cost was ultimately about $475 million (up from the $420 million for its original three-month mission).

"NASA's gotten what they wanted out of this mission," said Doug McCuistion, director of the Mars Exploration Program at NASA Headquarters in Washington. He noted, however, that Phoenix's "demise is a little earlier than we'd hoped."

Touching Martian water

Phoenix's big finding was to confirm the presence of water ice under the surface dirt layer in the northern plains. Phoenix "fulfilled dreams of touching Martian water for the first time," McCuistion said.

It also found that the dirt at the lander's location was more alkaline than the soil sampled by the Mars Exploration Rover missions (Spirit and Opportunity) closer to the equator. Phoenix's measurements also unexpectedly turned up signs of perchlorate, a possible source of energy for any potential life that could have once graced the Martian surface.

Phoenix's science team will now begin a thorough analysis of all the data received from the lander, said the mission's principal investigator, Peter Smith of the University of Arizona in Tucson.

"Phoenix has given us some surprises, and I'm confident we will be pulling more gems from this trove of data for years to come," Smith said.

The mission was "definitely the thrill of my life," he said.

Diminishing power

The lander's power supplies steadily diminished in recent weeks as the sun dipped toward the horizon with the approach of fall and winter to Mars' northern hemisphere. Phoenix went into its inactive safe mode briefly on Oct. 28, when a dust storm obscured the sky and limited the amount of sunlight hitting the lander's solar arrays. Phoenix restarted once the sun came up the following day.

For the next few days, Phoenix lost power or "browned out" at night, then woke up again the following morning when sunlight hit its solar arrays. Mission engineers tried to turn off any unnecessary instruments and heaters to keep the batteries alive, but "we were unsuccessful in keeping the batteries from browning out," Goldstein said.

The team was planning to send new instructions to the lander, but "unfortunately that high condition of dust lasted for some days there" and kept Phoenix from operating, Goldstein said.

The sequence of events that led to Phoenix shutting down was "exactly play-by-play what we anticipated doing," Goldstein said, though they came about three weeks earlier than expected. Mission engineers had originally hoped the lander would last through the end of November, acting as a weather station and using its camera to photograph the change of season.

Phoenix has effectively ended all science operations, though the team will keep listening for any signals from the spacecraft relayed through NASA's Mars orbiters for three more weeks, until the start of solar conjunction (when the sun comes between Earth and Mars).

The sun goes down about 5 minutes earlier every day at Phoenix's location. Come April 1, it will set completely beneath the horizon for three months. The sun won't be high enough in the sky to generate enough energy to power Phoenix again until at least mid-October 2009, Goldstein said. He thinks it's unlikely that the spacecraft will re-awaken even then, due to the damage done by extreme cold and carbon dioxide ice over the coming months.

Though no one on the team expects that Phoenix will once again live up to its name and rise again, there's always the "hope that the vehicle will surprise us again," Goldstein said.