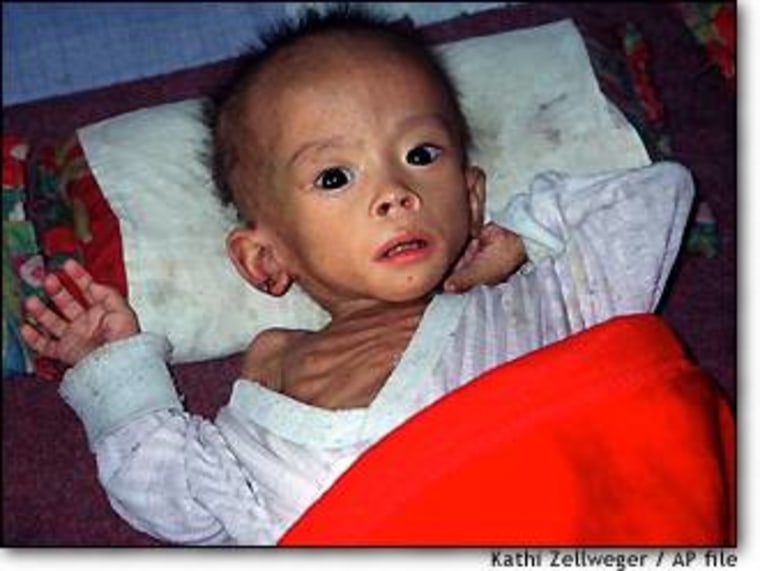

Lost in the clamor over Pyongyang’s apparent nuclear ambitions, a second crisis is escalating — a worsening food shortage in the nation of 22 million people. So broken is North Korea’s economy that the nation now relies on foreign donors for as much as one-third of its food. But the government has alienated some of the biggest donors — most notably the United States — and it is increasingly clear that its people will suffer for it.

Internataionl food aid poured into North Korea in the mid- to late 1990s, in response to a devastating famine. The worst of the crisis passed, after an estimated 1 million people starved to death, but most of the country continues to live at the edge of hunger. Even in better years, the country has a short growing season, a poor distribution system and very little to offer in trade for food. Recent economic reforms in the communist system have made food more expensive, and promise to boost the economy only in the the long term.

“North Korea has become a ward of the international donor community,” says Peter Beck, director of research at the Korea Economic Institute. “Most famines end. But the problem with North Korea is that it is of an institutional character.”

And this year, amid a crisis over Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions and sheer frustration with the insular regime, aid has plummeted. Contributions from the United States, Japan and South Korea — accounting for about 90 percent of World Food Program aid in the past — have been severely curtailed.

"We have already cut off 3 million people, and staggered resources for remaining recipients so we can stretch it as far as we can,” says WFP spokesman Khaled Mansour. “It is an exercise of triage, deciding who we can feed and who we cannot.”

The U.N. program is now geared to supplement the meager diets of about 6.4 million people, most of it to children and pregnant women. But even that appears imperiled. “Deliveries have fallen well short of needs,” said a WFP statement this week. “It is crucial that more contributors come forward quickly, because there is nothing in the pipeline beyond June,” the statement said, quoting Rick Corsino, WFP director for North Korea.

A little help, a little late

Despite a tense standoff over North Korea’s apparent nuclear ambitions, the Bush administration insists that it does not use food as a weapon. U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell visited the region in late February and announced that the United States would contribute 40,000 metric tons of food for North Korea in response to the World Food Program’s annual appeal. Powell said an additional 60,000 tons could be made available later in the year.

But that 40,000-ton donation — about enough for the U.N. agency to maintain existing programs for one month — came in months later and far lower than U.S. donations in recent years. By comparison, the United States gave 155,000 tons of food in 2002, accounting for more than half of the total received.

Facing questions about the slower and later food pledge, Powell blamed the slow congressional action and said the United States would like to see other nations help fill the shortfall.

Food as leverage

But other Bush administration policies clearly offer food as a reward for good behavior, and threaten to withhold it as a punishment for bad behavior.

To get Pyongyang to back down on its pursuit of a nuclear program, the White House is pressing for a “multilateral solution” on the Korean peninsula, one that would require North Korea’s neighbors — Japan, South Korea and China to take part in tough action. The issue is to be taken up at the U.N. Security Council, which could lead to new sanctions.

These key Asian players have been reluctant to further isolate the North, for fear it will collapse or prompt more dangerous moves by Kim Jong Il’s regime. Even so, Tokyo has suspended a $10 billion aid package and told North Korea that it would not resume the process of normalizing relations until Pyongyang proves it has eliminated its nuclear weapons.

In December, South Korea and Japan followed the U.S. lead to cut off fuel oil shipments provided to North Korea under the 1994 Agreed Framework, a response to the news of North Korea’s uranium enrichment program, a violation of the same agreement. That step could also clobber the country’s food supply says Eric Heginbotham, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“It was the lack of energy that caused the famine of the late 1990s,” he says, because fertilizer plants ground to a halt.

The United States “doesn’t want to cut off humanitarian aid,” he says. “But we’re cutting off fuel when we know that food aid is scaling back, and we know that is going to cause famine.”

U.N. sanctions?

Sanctions could choke off North Korea’s small, but growing trade with Japan, South Korea and China as well as remittances from Japanese of ethnic Korean origin, worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Current tensions between Washington and Pyongyang flared in October when a North Korean official reportedly admitted the country had a uranium enrichment program, prompting the United States to cut off fuel oil supplies. Pyongyang kicked out U.N. nuclear monitors and last week restarted its Yongbyon nuclear reactor, which had been mothballed since 1994.

Kim’s regime continues to push its nuclear agenda, in part to pressure the United States into direct negotiations, which it hopes will lead to a non-aggression treaty and eventually, normal diplomatic ties. The Bush administration says there will be no negotiation — and no carrots — until the North gives up its nuclear program because it doesn’t want to reward Pyongyang’s bad behavior.

“The carrots are out there,” Powell said, talking to reporters about aid on his flight back from Asia last week. “But before the carrots begin to be delivered we can’t do it in the face of this deliberate in-your-face violation of their obligations.”

Seoul under pressure

The food crisis in North Korea is growing at a time when there are also growing competing demands on aid — a severe famine threatening parts of Africa, ongoing needs in post-war Afghanistan and a humanitarian crisis looming in the event of an Iraq war.

Politics in Seoul will play a major role in the delivery of future aid. Under the government’s “sunshine policy” toward North Korea, the South became the second-largest food donor through the World Food Program in 2002 — giving 100,000 tons. It also gives direct aid to North Korea, including fertilizer in the planting season. So far this year, in part because of a leadership transition, South Korea has not yet made a World Food Program pledge.

New President Roh Moo-hyun vowed to continue the country’s dovish policy toward Pyongyang and promised to resist pressure from Washington, which has 37,000 troops stationed in South Korea, a legacy of the 1950-53 Korean War.

But Roh is under more pressure from both sides than his predecessor. Some of the euphoria surrounding the sunshine policy has faded, with more South Koreans questioning why the North has not done more in return. The Bush White House has been openly skeptical of Seoul’s “sunshine policy,” which undermines its efforts to put pressure on Pyongyang.

In meetings with Powell, Roh reportedly agreed that there should be some type of “multilateral approach.”

A wild card in the equation is China. Despite Washington’s protests, Beijing continues to be a major aid supplier to North Korea — with a combination of aid and concessionary trade of around $500 million a year. Beijing does not publicize the numbers, nor the beneficiaries of its programs, but Korea experts speculate that China’s aid to North Korea, a long-time communist ally, goes not to the most needy, but to the military and elite. Beijing does not want a nuclear-armed North Korea, but more immediately, it fears a collapse of the regime, which could drive thousands of refugees into China and lead to U.S.-domination of the Korean peninsula.