As Lai Wiriadi, 70, shuffles through the wreckage of his home, his feet crunch on the broken glass of Coke bottles, smashed by looters in an orgy of destruction last Thursday. His wife Wang Nan Xiu sobs, telling of all the things that were stolen-all the appliances, the baby formula, the medicine, even the ceiling fan. On the white walls, in fresh red paint, are messages they left behind: “Die Chinese,” and “Chinese go home.”

This is home to Lai, who came from China in 1932 and set up his tiny auto parts shop here on Warung Buncit Street. His family-including 19 children and grandchildren-live on the second and third floors, above the shop, which was also devastated.

Even more shocking to the family was that the looters should know all this. Most of them were familiar faces-men and boys from this neighborhood, who carried out the destruction while the family huddled on the top floor. “My heart is sick,” says Lai. “Some of these people were customers.”

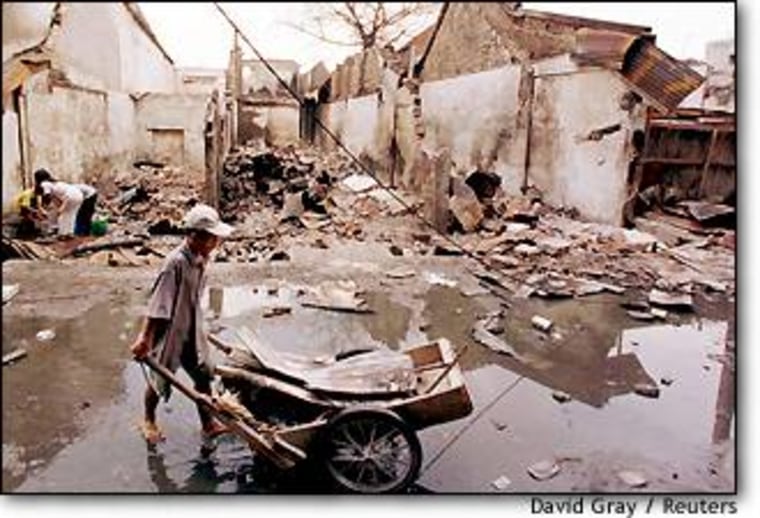

There are thousands of sick hearts in the city, as people come out to survey the damage done in the riots that left whole sections of Jakarta charred or gutted. It is clear that most of the targets were homes and businesses owned by ethnic Chinese, who as a group dominate the Indonesian economy. And there is growing fear and anxiety that indigenous Muslims, known as Prebumis may take to the streets again and vent their frustration over relative hardship, which has deepened with the ongoing economic crisis.

Those without private jets

The sad irony is that many of the Chinese Indonesians who remain to bear the brunt of the frustration are themselves middle or lower class citizens-not the handful of tycoons who have made their wealth through close ties to President Suharto. The super rich chartered planes out of the country when the riots started and left security forces to guard their property.

“Why do they attack us?” asked a woman in her 20s whose extended family lost two electronics shops in the flames. “We don’t have any connection to the president… Now we have to lay off some of our employees, and most of them are (prebumi). I’m sorry to complain to you, but I helped my parents build the business, so I’m hurt badly. Could you please inform my family of how to claim asylum or how to get out of here?”

Roots of the problem

The ethnic rift goes back to the early days of colonialism when Dutch businesses used Chinese merchants - successful throughout the region — as a kind of comprador class in what was then the Dutch Indies. But the Chinese’ dominant position was institutionalized by President Suharto, after he grabbed power from founder father President Sukarno in 1966.

In return for their patronage, and access to Chinese credit networks overseas, Suharto gave a handful of wealthy Chinese exclusive control over trade in key commodities, which became the underpinnings of multi-billion dollar empires. Paradoxically, throughout his three decades Suharto has also been instrumental for the repression of ethnic Chinese by allowing them to be scapegoats for social and political problems-including the communist threat, long after the threat was past.

Even today, many Chinese believe that the looters, while willing participants in the mayhem, were instigated by some force within the military, to divert criticism from the government. “Where were the military during the looting?” asks says Suriya, who lost his electronics shop in a blaze last week. “They were no where to be seen.”

The result of last week’s riots was a nearly total destruction of business districts in the heavily Chinese Glodok and Kota. These areas are estimated to generate a third of Jakarta’s wealth, and their loss mean that rebuilding the economy will take years, particularly given the ongoing financial crisis.

Strategies for safety

Since the most serious slaughter of ethnic Chinese in 1968-69, when an estimated 500,000 were killed, Chinese in Indonesia have developed a range of strategies to prevent attacks. Most have adopted Indonesian names like Hardoko or Suriya instead of Wang and Chen—and only use their Chinese names at home, if they have one.

To defuse jealousy among poor neighbors, many individual Chinese make shows of generosity at the main Muslim holidays, handing out free cooking oil and other goods. “You have to bribe them,” says one cynical Chinese computer professional. “You should not build big walls around your house, or they may want to attack.”

Appearances are of the utmost importance. One bank president told me that wherever he set up a bank branch, he donates heavily to building and maintaining the neighborhood mosque, and other high-profile social programs in the area. As a result, last week when mobs came, Prebumi neighbors of the bank came to its rescue. Some shopping malls and hotels took the more direct approach-paying off the armed forces to guard their property.

Homes and shops around the city (including Chinese-owned) are hung with signs declaring “Prebumi,” “I am Muslim,” and “Prebumi owned” hung by individuals-and even some foreign franchises-to discourage looters. Some places, like the 300 year old Sion Protestant church have hung signs stating “Pro-Reformasi”-affirming the need for serious political and social change: “Pro-Reformasi.” Heavily armed guards stand by at its gates.

The church, along with most major businesses in Jakarta, is closing its doors to wait out the potential turmoil of National Awakening Day on Wednesday, when thousands of protesters are planning to take to the streets, prompting fears that the peaceful demonstrations may again spark violent riots in the city.

Little to lose

At a covered market in south Jakarta that serves a predominantly prebumi area in south Jakarta-there was also anticipation, but seemingly little of the fear about the events to come. One vegetable seller said she doesn’t agree with the violence and looting, but admitted that she had not been able to stop her husband or son from going out and taking part of last week’s action. By all accounts, it will be “lively.”

These people’s view of politics is simple, underpinned by the stark reality of food prices soaring out of reach. Cooking oil has in the last week risen to 6000 rupiah from 3500 rupiah per liter. Chinese interests largely control this key products. So the poorest Muslims are understandably skeptical of political rhetoric. “Reform is good,” said a clothes vendor, “As long as it is real, deep change that really makes a difference.”

A growing number of Muslims and non-Chinese Indonesians also condemn the violence against Chinese, while sympathizing with the frustration that caused it. Students have sought to distinguish their movement from the mob behavior that it apparently sparked last week. At Trisakti University, a new slogan has surfaced: Reform means Democracy, not Discrimination.”

Beginnings of tolerance

In many neighborhoods in the cities, Chinese and Prebumis have formed night patrols to guard against looters. A Prebumi business executive employed by an American company voiced the overwhelming view among Indonesia’s better-educated population: “Our problem is not the Chinese, it is the president.”

But the fear is that in this volatile environment, there will be no reasoning with mobs. At the Australian embassy, there is a growing line of visa applicants who have heard rumors that Sydney is prepared to be lenient or even grant asylum. Those who can scrape together the required 5 million rupiah ($500) exit fee are doing so.

Meanwhile, for Chinese Indonesians like 32-year old Suriya, who was wiped out financially when his parts shop was burned to the ground last week, the only thing to do is hunker down and wait. With the few others who turned out for Sunday’s afternoon service at Sion church in Glodok, he said a fervent prayer-for kindness, patience and tolerance.