With the fall of Tikrit, the end of the combat in Iraq neared, and plans for rebuilding the country and civil order got under way. But in some places, the war will not be over and rebuilding cannot begin until the deadly waste of war is cleaned up. Because of the U.S. use of “cluster bombs,” the war will almost certainly continue to claim victims after the fighting stops, as unsuspecting civilians stumble across the live explosives scattered throughout the country.

In this Iraq conflict, the Pentagon has highlighted its technology for intelligence-gathering and guidance systems that allow better targeting than ever before — and touted its efforts to avoid civilian casualties.

“We have the ability to hit, in most cases, exactly what we try to hit — and scale the munition appropriately to the task,” Army Maj. Gen. Stanley McChrystal told reporters in a daily briefing of foreign reporters in early April. He stressed the moral imperative of doing so.

But the use of precision-guided weapons — meticulously enumerated each day by the Pentagon — does not address the problems of old-fashioned cluster bombs, still in use in this conflict, which may hit their target but not explode until weeks, months or years later when a farmer or child stumbles across them.

“The Pentagon is crowing about the Air Force sparing civilians by using only precision weapons in Baghdad,” says Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch. “But that’s a meaningless achievement if the Army then comes along and indiscriminately batters civilian neighborhoods with cluster munitions.”

Cluster munitions, which can be launched by air or ground, come in many forms, but what they have in common is this: A single dispenser delivers many smaller explosive devices to the target.

As an example, the Multiple Launch Rocket System can fire 12 missiles in rapid succession, each rocket containing 644 “bomblets.” Thus, in just a few minutes this system is capable of delivering some 7,728 explosives, each about as lethal as a land mine. The idea is to blanket an area where there is a concentration of enemy troops or equipment. The advantage of cluster bombs, say some military experts is that they can broadly target personnel and equipment without the deep damage to roads and infrastructure incurred by a single large bomb.

The problem is that anywhere from 5 percent to 30 percent of the submunitions or “bomblets” fail to explode on contact, depending on conditions, and lie dormant until they are disturbed. Like land mines, the unexploded ordnance tends to take the lives of civilians, very frequently children who mistake them for toys, when they come across them long after the conflict.

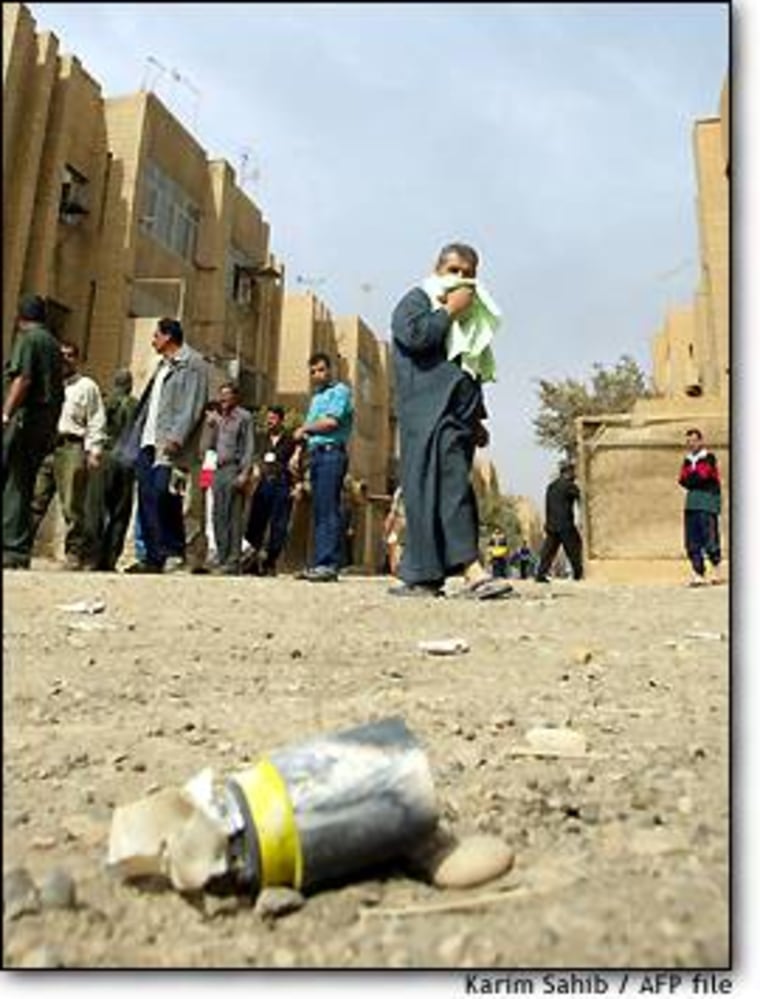

News reports, and the photograph above, strongly suggest the use of cluster bombs in Baghdad itself.

“It’s a very clumsy, indiscriminate weapon,” says Gordon Weiss, a media representative at the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). “It basically waits for a target to walk into it.”

Hillah: 'Still pending'

Humanitarian groups are especially alarmed by the apparent use of cluster bombs in heavily populated civilian areas, including a devastating strike on the town of Hillah, where at least 11 civilians died and dozens were injured in the first days of April. The Pentagon says the investigation into the Hillah strike is “still pending.”

Footage from the scene provided by the French news agency Agence France-Presse clearly shows unexploded BLU-97 submunitions, according to Richard Lloyd, director of the U.K.-based non-profit group Landmine Action. The International Committee of the Red Cross has said that civilian injuries were consistent with cluster bombs.

Though it has not yet addressed the Hillah incident, the Pentagon readily confirms that it has continued to use cluster munitions in this conflict but will not reveal the extent or type used.

Military expert Bill Arkin, an adviser to NBC News, says U.S. forces have used a variety of cluster munitions in this conflict:

Multiple-Launch Rocket System: As mentioned above, the MLRS is a surface-launched system containing 12 M26 missiles, each designed to deliver 644 submunitions, and fired in rapid succession. Use of this munition was also verified by Human Rights Watch arms experts.

Army Tactical Missile System: ATACMS is a ground-launched missile system consisting of a surface-to-surface guided missile for hitting concentrations of military personnel and equipment. Each missile carries 950 bomblets.

Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser: The WCMD kit is used with air-launched cluster bombs, to correct for wind and other factors that affect the dispenser’s accuracy. The system is used with a variety of submunitions.

Joint Standoff Weapons: JSOW is a precision-guided missile that allows the pilot to launch the missile carrying submunitions a safe distance from the target. It can carry a variety of submunitions.

Rockeyes: This clamshell-shaped dispenser holds 247 dart-shaped bomblets, especially effective against armor and soft-skinned targets, which free fall over a 3,300-square-yard area and detonate on impact. Rockeyes were widely used in the 1991 Iraq war, and have a notoriously high failure rate.

In addition, Landmine Action’s Lloyd says his group has identified at least three variants of cluster munitions used by British forces in Iraq.

It is too early to know exactly how extensive the use of cluster munitions has been, but the United States and many other countries continue to defend their use as “appropriate for specific targets.”

Among their strategic uses is “to create an obstacle for a tactical purpose,” said Chief Diane Perry a spokeswoman at the Defense Department.

“There are some who oppose cluster bombs, but the military doggedly supports them despite the enormous challenges in how to deliver and explode them,” says military analyst Arkin. In the Gulf War, “we threw cluster bombs everywhere with virtual disregard for human populations.”

Littered with explosives

What is clear is that their use further complicates the job of de-mining experts who have been working in Iraq for years, trying to clear areas that are littered with unexploded cluster bombs as well as layers of landmines left from the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, the 1991 Gulf War and the current conflict.

Even before this conflict, Iraq had created the greatest demand in the world for prosthetic limbs, following Afghanistan, largely owing to encounters with landmines and unexploded bombs.

Years of lobbying finally led to an international treaty banning landmines, based on the notion that landmines killed indiscriminately. (The United States is not a signatory to this treaty, in large part because it supports the use of landmines as a barrier between South and North Korea.)

Based on the same logic — since unexploded munitions effectively create a minefield — humanitarian groups have been pushing for a treaty on cluster bombs that would require any country that used the munitions in conflict also to be responsible for clearing those areas after the conflict.

There is little hope of banning cluster munitions outright — they are held in arsenals around the world.

But in a bow to public sensitivity about the use of cluster bombs, the United States is improving on its munitions. Some new ones actually defuse themselves if they do not hit a target with a specific thermal signature — say, that of a tank.

And under the Clinton administration, the Defense Department decreed that cluster munitions manufactured after the start of 2005 must have a failure rate of 1 percent or less.

However, humanitarian groups note that the United States has more than one billion of the old-fashioned submunitions in its stockpiles now, and there is no indication that they will not be used in future conflicts.