Armando Castillo knew he should not attempt the last treacherous stretch up Half Dome with storm clouds looming. But he felt he had come too far not to accomplish his goal.

So up the side of the slick, granite monolith he went, 400 vertical feet at nearly a 40 percent grade.

"About three-quarters of the way up it started hailing," he said. "There's a bunch of people and everybody just stops. Some women started crying because it was slippery and pretty scary. Then it cleared up."

While others turned back, Castillo pushed on up the park's iconic feature, making him one of Yosemite National Park's worst nightmares— the increasing number of wilderness neophytes who mistakenly think the government is obligated to save them.

"People are pushing their luck, trying to beat the weather, and their backup plan is to call for a rescue," said Mark Marschall, project manager for the Half Dome interim permit program. "They're not understanding what that means. We can't fly in that kind of weather. They're on their own."

The problem has surfaced in recent weeks on the park's most inspiring hike, where visitors confronted by unseasonable rains are ignoring warning signs and common sense. With less than a month to go until the Half Dome route is closed, park officials are making a rare appeal for visitors to use discretion on the trail.

"Over the last few weekends we've had some lightning and thunderstorms on Half Dome, but people are still going up," said park spokesman Scott Gediman, who adds that for two weekends in a row people have called 911 for rescue.

Some callers tell the dispatcher they want to use their platinum credit card for the free helicopter ride some companies guarantee in an emergency. Park officials don't charge for rescues — nearly 1,000 rescues cost more than $2.5 million between 2007 and 2010 — but neither do they fly in dangerous weather.

Castillo, with six hours of hiking behind him, made a poor choice.

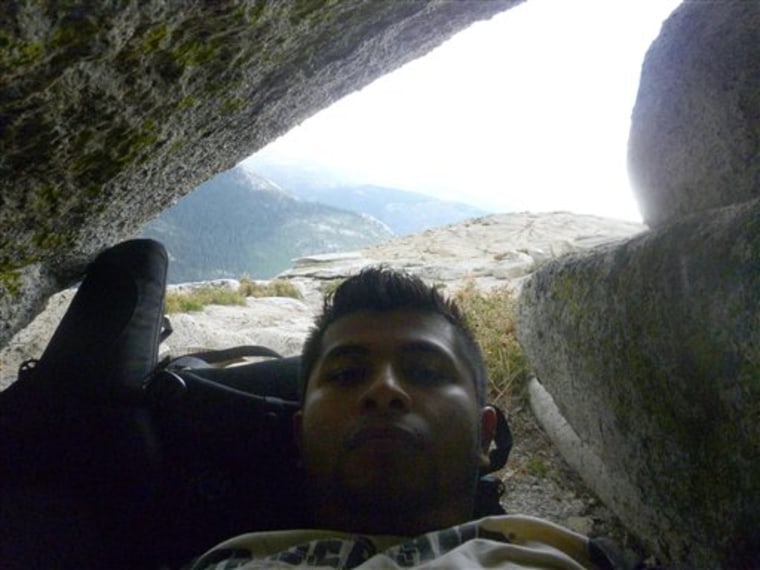

The salsa dancer from Hayward, Calif., soon found himself trapped at the 8,842-foot summit in a freezing thunderstorm. Soaked and shivering, he huddled under a rock with four other terrified hikers. Then he called 911, thinking he was going to die.

I'm wet and I'm shivering and I'm really cold right now, Castillo pleaded to dispatchers.

A sign at the bottom of the cables warns hikers not to attempt Half Dome if weather threatens — and rangers try to issue verbal warnings.

But 20 people have died on Half Dome over the decades, nearly all with rain as a factor, officials say. One of the two to perish this year was a Bay Area woman who slipped in a July storm and fell 800 feet. (A total of 13 died in park mishaps this year, the most in decades — including three swept over a raging waterfall on the trail to Half Dome.)

"People make poor decisions for a lot of reasons," said Kevin Killian, deputy chief ranger. "What it comes down to is a lack of clarity in peoples' risk assessment. What is the true hazard and what are my bailout options?"

Half Dome sits at the east end of Yosemite Valley, its face cut flat by retreating glaciers looking almost as if a bowling ball were cut in half. It is accessible to anyone with a pair of hiking boots and the physical stamina to ascend 4,800 feet over eight miles. Metal cables anchored by poles allow hikers to pull themselves up the final stretch of worn-slick granite. Every 10 feet a 2x4 braced by the poles sits atop the path to provide a resting spot, a non-slip spot for hikers to brace their boots.

After a man on the rain-soaked granite slipped to his death from the cables in 2009, the park launched a permit program this year, which limits the climb to 400 hikers a day roughly June through October.

Whenever Gina Bartiroma hears about another tragedy on Half Dome she recalls June 6, 2009 — the day she slipped in a freak snow storm, then slid 140 feet before her broken body caught on a eight-inch ledge. She broke her back, fractured her skull and is still suffering memory lapses from a traumatic brain injury.

"We got to the top and it was so cloudy, all I could think was let's get down," said Bartiroma. "I was tired and I was hungry. My arms weren't stable, and being cold, it all factored in."

After 911 dispatchers told Castillo and other hikers they were on their own, he cowered under the rock to escape the rain for three hours. When the rain stopped, the group waited for the granite to dry before heading down as the sun dropped low on the horizon.

"I was freaking out and thought I wasn't going to make it," he said. "But then I remembered that because of my dancing I was in a better position than most people.'"

Most slid on their butts, he said. He started out on foot, slipped and broke a potentially long fall by snagging the cable with one hand. Frightened, he sat on his butt and scooted down the rest of the way.

"After the fact I realized it's the wilderness and they're not supposed to do anything, but I did go in expecting a little more of a warning," said Castillo, who plans to return.

The day after Castillo called for help, a group of 20 hikers called 911, not understanding that the very rain storm threatening their lives would also endanger a ranger.

"We have to decide 'Can we really expose rescuers to the risk that is present?'" Marschall said. "Can we commit a helicopter in the middle of a rainstorm with the potential of lightning? The answer is typically no."

_____