They're about an inch long, head to tail. They feast on flakes. To anyone uninitiated in the intricate hierarchy of fish, they're likely to be mistaken for lowly guppies.

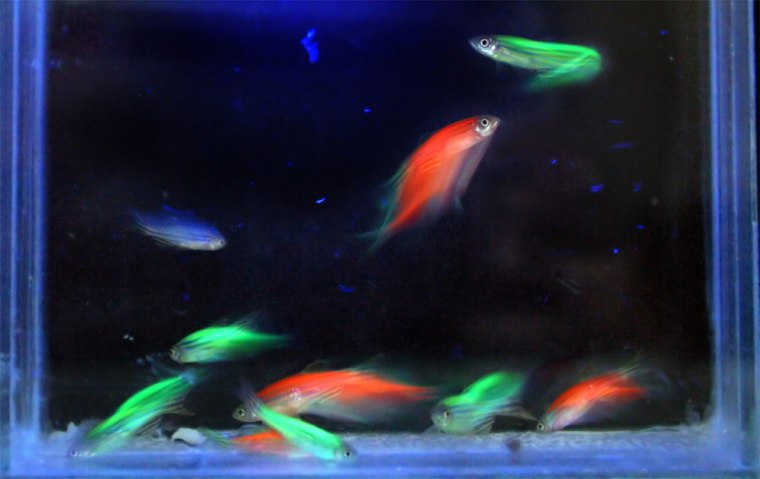

But because they also emit a distinct red glow, the zebra danios sold at stores under the name GloFish carry a lofty claim to fame: They're the nation's first officially sanctioned genetically modified pet.

Scientists say they won't be the last. In their native South Asia, zebra danios are usually black-and-white striped, not red. Nor do the fish ordinarily shine intensely under black light, as the GloFish does. It takes the insertion of a gene from sea coral to make the zebra fish a GloFish.

So if researchers can create fish that glow like coral, who's to say they can't one day engineer dogs that meow like cats? Although such creatures are more likely to be found in science fiction than in laboratories at the moment, an industry in gene-altered pets is already on the way.

"GloFish is minor compared to what we could see in the future," said Scott Angle, a natural resources professor at the University of Maryland.

In the three months since the Food and Drug Administration decided that the aquarium pet need not be regulated, the GloFish has gone from curiosity to a focal point in the debate over biotechnology.

Ethics questions

Most scientists agree GloFish poses little danger to human health or the environment, but a public interest group has sued the government to stop its sale until the fish can be reviewed more thoroughly. Meanwhile, GloFish is piscis non grata at the nation's two largest pet store chains, Petco Animal Supplies Inc. and Petsmart Inc. A Petsmart spokeswoman said it wants more scientific data about the fish, while Petco spokesman Shawn Underwood said the company has an ethical problem with the idea of altering the genetic makeup of an animal "when there's no purpose besides our pleasure."

The pet industry is in many ways a peculiar venue for such a heated debate over the wisdom of genetic modification. The whole notion of a pet, after all, is based on generations upon generations of selective breeding aimed at drawing out certain characteristics that make animals more suitable companions. Advocates of genetically engineered pets point to that history, and question whether changing an animal's genes with a syringe is all that different.

"It's the same result. Except one is 'natural' and one is 'not natural,'" said Perry B. Hackett, chief science officer of Discovery Genomics Inc., who served as an adviser on the GloFish project and is a passionate supporter.

Ramifications unknown

But other experts are more skeptical, reasoning that the science behind gene alteration is still in its infancy, and the ramifications of such rapid changes in the genetic code are unknown. They question, too, whether such cutting-edge science -- normally touted for its ability to create new ways to feed the hungry or heal the sick -- should be used for such frivolous purposes.

Skeptics say those kinds of commercial applications are of limited social value, yet they pose the same risks as any other genetically modified organism.

"You're not producing any more food. You're not making the environment any cleaner. And you're not making anyone healthier," said Angle, who specializes in the environmental impact of gene-altered organisms. "So the question is: Is it worth the potentially very serious risks to have the benefit of having a novel pet in your aquarium?"

To Alan Blake, 26, Texas-based Yorktown Technologies LP's chief executive, the answer is an emphatic yes, not least because he doesn't see the GloFish as a threat to anything -- except, perhaps, public ignorance about biotechnology.

Blake and his high school classmate, Richard Crockett, founded the company to capitalize on fish that were originally developed in a Singapore laboratory for use as a modern-day canary in a coal mine: The fish were supposed to indicate, by glowing, if a given body of water was polluted. So far, the natural warning system is still a work in progress; once the fish started glowing, scientists couldn't figure out how to stop it. But Crockett and Blake saw commercial potential for a freshwater fish that could light up aquariums across the United States, and teach people -- especially kids -- a thing or two about biology in the process.

"We really wanted to be able to get them out of the lab and share them with the public," Blake said. To do that, he said, he had to convince regulators that the fish were safe.

Mounds of data

Blake said he presented the FDA, as well as state officials, with mounds of scientific data showing that the GloFish doesn't pose any more danger to public health or the environment than regular zebra fish, which have been sold in this country for decades. Fears that a GloFish set loose in the sewers might breed and ultimately spawn oceans full of luminescent fish, he said, have no basis. Regular zebra fish have never been able to survive in American waters because it's too cold for a species that thrives in the tropics. If anything, Blake reported, GloFish were less tolerant to cold than their non-glowing counterparts.

The FDA apparently found Blake's arguments persuasive: It issued a three-sentence statement in December giving GloFish a clean bill of health, declining to regulate it.

Blake contends the review was thorough. "This is the most intensely scrutinized fish ever to hit the ornamental fish market," Blake said.

But many scientists say the FDA gave GloFish a pass, and in the process established a dangerous precedent for genetically engineered animals not being used for food, medicine or research. Eric M. Hallerman, a professor of fisheries science at Virginia Tech, agrees that GloFish pose little risk to the environment in the United States. But as a matter of policy, he thinks the pet should have been subjected to a formal and comprehensive review. "If this had been a food or a drug," he said, FDA "would have demanded a lot more data."

The real problem, Hallerman said, is that the regulations governing genetically modified organisms are "a patchwork," with many having been written long before anyone could conceive of a fish that's part sea coral. "You have gaps in the system, and this is just about the best example I can think of," he said.

Floodgates opened?

Hallerman and others said a danger of unregulated gene-altered pets is that they could upset the natural balance in the wild: For instance, a tropical fish that's made more cold-tolerant could ply the Potomac and drive out native species.

The Center for Food Safety, an organization that seeks limits on biotechnology applications it considers potentially harmful, has filed a lawsuit challenging the FDA's decision not to regulate GloFish. The group said the government's action sends a message to those producing genetically modified pets that they can sell unproven animals with impunity.

As evidence, the group points to a Chicago-area store called Living Sea Aquarium that carries a green-glowing genetically modified medaka, even though that fish hasn't been subjected to review by U.S. regulators.

"The GloFish has absolutely opened the floodgates to a whole new pet trade in genetically engineered animals," said Joseph Mendelson, the center's legal director. "Meanwhile, our regulatory agencies are asleep at the wheel."

Officials at both Living Sea Aquarium and the wholesaler that supplies the genetically modified medaka, New Jersey-based International Pet Resources, said they were unaware the fish, which is sold legally in several Asian countries, had not yet been reviewed by U.S. regulators. Both companies said this week, after receiving inquiries from a reporter, that they would no longer sell it.

FDA spokeswoman Rae Jones said the agency, which has taken the lead at the federal level in regulating genetically modified animals, would not comment on GloFish, the medakas or on its approach to regulating such organisms because of the pending lawsuit.

Barbara Glenn, director of animal biotechnology at the Biotechnology Industry Organization, a trade group to which Yorktown Technologies belongs, defended the FDA's decision.

Future applications

To Glenn, genetic modification can be advantageous to both people and pets. Researchers are already at work trying to create a cat that won't aggravate its owner's allergies. Other possible creations include a dog that isn't as susceptible to hip dysplasia, an ailment common among German shepherds and Labrador retrievers that's associated with over-breeding.

Other applications could be more difficult to justify. "There's always going to be a market for the bizarre," said Andrew S. Kane, director of the University of Maryland's aquatic pathobiology program, who opposes the idea of genetically modifying pets. "It's super cute or it's super soft or it has the shortest hair or it doesn't shed. There's always going to be a desire for that."

Whether there's a desire for glowing fish remains an open question. Blake said GloFish sales have been impressive at stores where it's sold at the suggested retail price, $5. But many stores have priced the fish out of the market by marking it up to $10 or higher; normal zebra fish retail for less than a buck.

At local pet stores, reviews have been mixed. Some stopped carrying GloFish when more people came to gawk than to buy. But Tom Senyitko, owner of Wally's Aquarium in Alexandria, said the fish have been popular, especially among parents.

One person who won't buy is Andrew Blumhagen. The Silver Spring resident is a serious aquarium hobbyist, with about a dozen tanks and upward of 200 fish. Many are naturally occurring variations on the zebra fish -- including ones that, while not exactly glowing, do exhibit shades of gold, blue and red.

He doesn't have a problem with genetically altering fish. He just doesn't like the way GloFish look. "It's an aesthetic question," said Blumhagen, 31, who leads the Potomac Valley Aquarium Society, an organization of about 120 hobbyists. "There are just many more exciting fish out there."