The discovery of a nearly Pluto-sized object way out beyond the known worlds could jeopardize the status of Pluto as a planet, adding fresh fuel to an argument among astronomers that is likely to last years.

In the end, our solar system will either shrink to eight planets, grow to more than a dozen, or contain a glaring asterisk born of an emotional attachment to the diminutive Pluto.

The object announced this week, called Sedna, adds impetus to an effort by the International Astronomical Union to define just what is and is not a planet. The IAU has no specific plans to directly challenge the planetary status of Pluto. But the decision by a working group within the IAU could have that effect, an official said Wednesday.

"Whether or not one needs to do anything about Pluto will depend on what the definition of a planet will be," Iwan Williams, president of the IAU's Planetary Systems Sciences division, told Space.com.

The process could fester into 2006, when the group holds its next General Assembly. And whatever the ruling, there will likely be astronomers who try to keep the debate alive after that, another astronomer familiar with the process said.

No definition

Until now, scientists have not had a set definition for the term "planet." In recent years, many potential parameters have been kicked about, from an object's roundness to its distance from the sun and the shape of its orbit. Even where it formed is a consideration.

"If the answer was obvious, there would be no need for a working group," Williams said.

The IAU decides on names and classification systems for all solar system bodies, among other duties. Williams outlined what might happen in this decision process:

"The specific question of whether Pluto is a planet or not would only arise if it turned out clearly not to be one by the definition, but for historical and cultural reasons, the community wished to keep Pluto as a planet."

Since the 1997 death of Pluto's discoverer, Clyde Tombaugh, many astronomers have increasingly urged the IAU to downgrade Pluto. The flap surfaced publicly in 1999, when rumors swirled that Pluto was going to be stripped of its planetary status. Articles about the possibility generated widespread public disapproval.

The 1999 fracas was not spurred by the IAU, however, and the international organization ultimately issued a press release stating its regret that "incomplete or misleading" press reports on the status of Pluto "appear to have caused widespread public concern." The statement went on to assure the public that "no proposal to change the status of Pluto as the ninth planet" had been made within the IAU.

Dual status

Many astronomers have since been content to let the IAU and the public call Pluto a planet, while most of them think of it as a Kuiper Belt object, one of many frozen worlds beyond Neptune. Some fight actively for Pluto's demotion, while others think Sedna and its like should join the cast of planets.

In the meantime, scientists still have not defined planethood. Sedna, the strange new world, has only increased the need for sorting out the terms of the solar system.

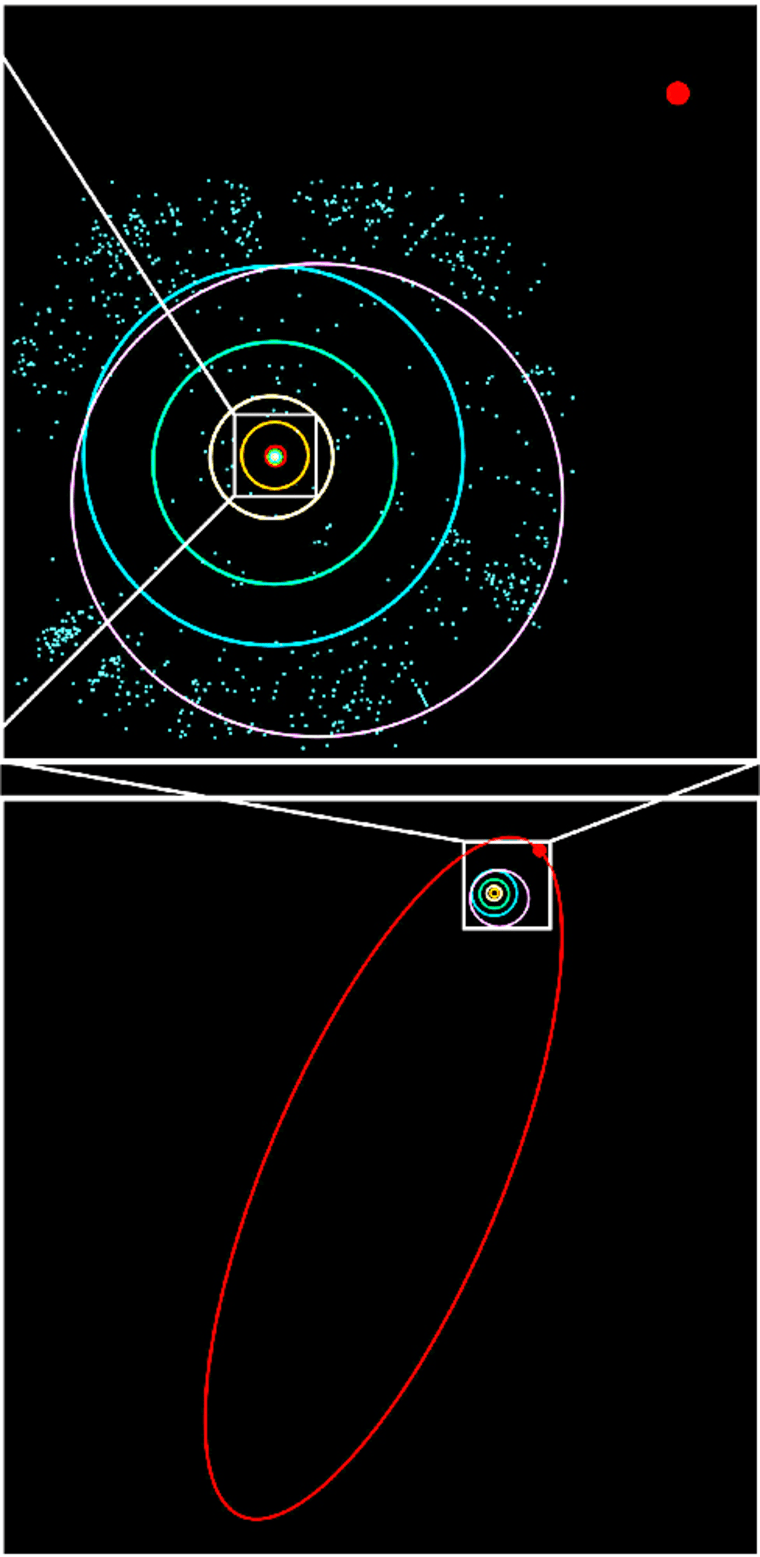

Sedna is about three-fourths Pluto's size and is presently about three times as far from the sun. It ranges much farther into space on a long, elliptical orbit around the sun that takes 10,000 years to complete. It is frigid and almost surely lifeless. But it is round, like the nine planets. It's probably made of rock and ice, though astronomers don't know its exact composition.

Several astronomers have said that if Pluto is a planet, then Sedna should be considered a planet.

On the flip side, however, some of those same astronomers prefer the catch-all term "planetoid" for both of these round but small worlds. Classification systems, they argue, will work themselves out only after more objects are found and astronomers glean a better understanding of the suddenly more mysterious outer solar system.

The accident of Pluto

For years most astronomers have said that Pluto is an accident of observational history and should never have been called a planet. Pluto was discovered by Tombaugh, an amateur astronomer, in 1930.

"When Pluto was given planet status, its diameter was thought to be nearly 15,000 kilometers [9,320 miles], 12 percent larger than the earth," Williams, the IAU official, points out. "In terms of size, it was the fifth planet rather than the ninth."

And for decades after Pluto's discovery, no other objects were discovered beyond Neptune. In recent years, however, other round objects about half Pluto's size have been detected in the Kuiper Belt, much closer than Sedna. Michael Brown, a Caltech astronomer who led the discovery of Sedna and two other good-sized worlds, expects there are more.

In fact, there's even the chance of an Earth-sized planet lurking out there, he and others say.

Pluto's plight involves many factors. It is about 1,413 miles (2,274 kilometers) wide -- smaller than Earth's moon. But most astronomers don't see that as a disqualifying factor.

More significant, Pluto is inclined 17 degrees to the main plane of the solar system in which the larger planets orbit. Other planets have inclined orbits, too, but none compare to the leanings of Pluto. Its orbital path is also very non-circular; it ranges between 30 and 50 astronomical units from the sun. One astronomical unit, or AU, is the distance from Earth to the sun, about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

Sedna's travels are even stranger in one sense. It roams from 76 to 1,000 AU from the sun. Sedna's inclination is 12 degrees, less than that of Pluto.

"It blurs the line between what is a planet and what is not," said Alan Boss, a planet-formation theorist at the Carnegie Institution in Washington. It also blurs the line between the Kuiper Belt, where Pluto resides, and the more distant Oort Cloud, a reservoir of comets that stretches halfway to the next star.

Scientists have not known what, if anything, exists in a possible void between the two regions. But at the least there is Sedna, officially catalogued as 2003 VB12. Now they don't know where to stick this latest discovery. They can't even be sure where it formed, and they're very unsure as to how it got such an odd trajectory.

"It blurs all sorts of lines," Boss said.

Embarrassing

"It's something of an embarrassment that we currently have no definition of what a planet is," Gibor Basri of the University of California at Berkeley has said. "People like to classify things. We live on a planet; it would be nice to know what that was."

Basri has previously proposed simply setting a lower diameter limit for planet status, including all objects orbiting the sun that are about 435 miles (700 kilometers) wide or more. That's roughly the bulk needed to allow gravity to shape an object into a sphere, depending on density. Smaller objects — both asteroids and comets — tend to take on odd shapes like that of a potato.

Basri's simple definition would boost the tally of planets in our solar system to more than a dozen based on presently known objects, including Sedna. And it would leave Pluto as a planet.

Many astronomers, though, simply don't see a solar system with more than eight planets.

"Scientifically, there really is no question" that Pluto should be reclassified, says Michael Brown, the Caltech astronomer who led the discovery of Sedna.

"Either Pluto is not a planet, or many other things are planets," Brown said Wednesday. "Which is a better choice? I want my planets to be more special, not less special, so I favor Pluto not being a planet. Emotionally, though, I have to admit that I have grown up thinking Pluto this special oddball planet at the edge of the solar system. While I now know scientifically that Pluto is less special, it's still hard to let go."

Tough job

Whatever the IAU working group decides, the process might stretch out for two years before any decision is rendered, if at all.

"If it was felt that Pluto required special status, then ratification at the next General Assembly would be called for," Williams said. That IAU meeting will be held in Prague in 2006.

Boss, the Carnegie theorist, is not sure the issue will be settled even by then.

Boss does think the IAU's efforts are necessary and worthwhile. "It sort of sharpens people's thinking" about how the solar system is organized, he said. But it won't necessarily silence astronomers who have strong feelings one way or the other.

"Whoever gets shut out will continue to argue," Boss told Space.com. "I sure would not want to be on the working group myself."