An astronomer has turned observations of the early universe into a sound clip that represents a primal scream from the first million years after the Big Bang.

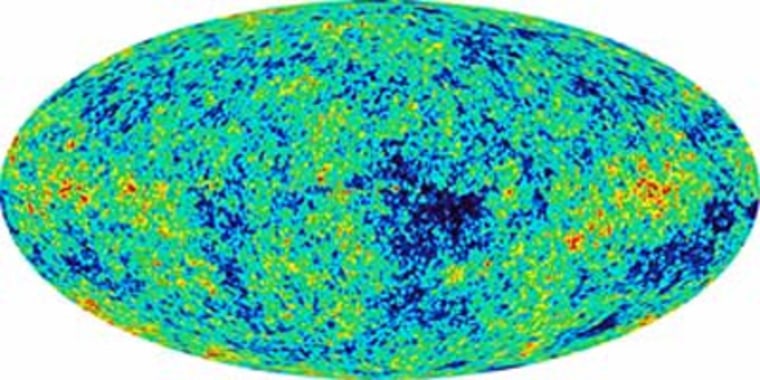

Mark Whittle, an astronomer at the University of Virginia, based the work on a "wonderful gift from nature," the cosmic microwave background that was unleashed when the universe was about 380,000 years old. At that point in time, a dense fog began to clear and radiation was first allowed to escape its natal cocoon.

Other studies have generated sound clips out of data from a black hole and even from our own solar system. But none have reached so far back in time and space.

Whittle first figured out the sound at the time of the cosmic microwave background, or CMB. Then he and colleagues made some assumptions about the dense state of things before the CMB and modeled the sound that likely occurred in the interval between the Big Bang and the release of the CMB.

Sound would have traveled easily through the early cosmos, he explained, because the more compact universe was denser, like a hot, thin atmosphere.

"If we want to access times before and after the microwave background, we have to make use of computer simulations," Whittle said here today at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

The simulations generated a growing hiss that resembles a roaring jet plane flying low overhead. It represents the first million years of the cosmos and it is compressed into about 5 seconds for easy listening.

"I was relieved," Whittle said. "I didn’t want the universe to be some wimpy, quiet thing. But I didn’t want it to be inhumanly, fatally loud. And it isn’t. It’s just loud … and that’s great, just great."

Whittle said that most people think the theoretical Big Bang starts out with a huge explosion, then it gets quieter with time.

"In fact, the Big Bang starts out completely silent," Whittle said. "The expansion … is purely radial — there’s no sideways motion. There are no pressure waves. What they are, are density variations on all scales, everywhere."

Rapid expansion

The universe expanded rapidly after the Big Bang, during a period called inflation. Later, it continued to expand at a slower rate as it cooled enough for gas to condense and form stars. All this time, density variations contributed characteristics to the sound that Whittle's team has determined.

"It’s nice to kind of get a clean handle on it," Whittle said. "It’s as if the universe is a bad concert hall. It has drapes and carpets which absorb the high frequencies. It deadens the sound. What you’d like to do is to put your instruments right in the middle of the orchestra instead of the back of the hall. And to do that you need to use computer simulations, which are quite accurate to access the pure sound."

The chord is somewhere between a major and a minor third, Whittle said, adding that he’s drawn to associating human emotions with music. "Majors are buoyant and happy chords. Minors are subdued and sad," he said.

"So at the time of the microwave background, the universe in a sense is between two states," Whittle said. "It opens its symphony on a major chord and subtly transforms into a minor chord."

Fine-tuning the cosmic concerto

Whittle told SPACE.com that he’s got other ideas for playing out the cosmic concerto. "This is getting more into tinkering. I’d like to fix the fundamental in pitch and then watch how the higher harmonics change."

Another idea, Whittle said, is to generate images of primordial sound waves, thereby weaving in other fields to help play out the birth of the universe.

"Just as the government likes … we’re doing sound science," said Steve Maran, press officer for the American Astronomical Society.

Maran said that Whittle’s work leads to a central observation: "The Big Bang was really the 'Great Silence.' We went from the Great Silence to louder and louder sounds and ended up with the stars we see today," Maran said.

Space.com's Robert Roy Britt contributed to this report.