Venus has just finished up an excellent appearance in the evening sky that began in November. Now the planet has disappeared into the twilight, but it will make a brief and dramatic return appearance Tuesday.

On that day, more than half the world will get to see an exceedingly rare event: Venus crossing the face of the sun at what astronomers call inferior conjunction. Observers located over parts of eastern, central and the far northern sections of North America will be able to observe at least the closing stages of this striking celestial phenomenon.

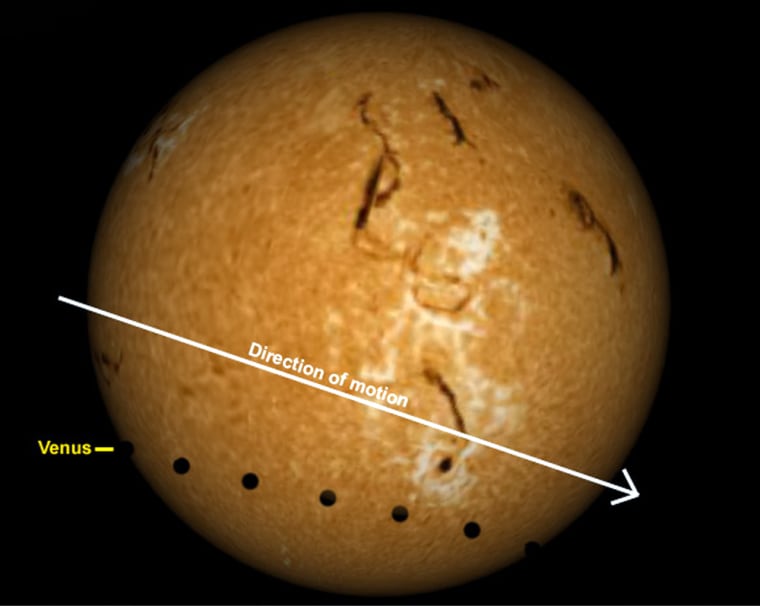

The entire transit, as it is called, will be an east-to-west passage taking just over 6 hours and 12 minutes.

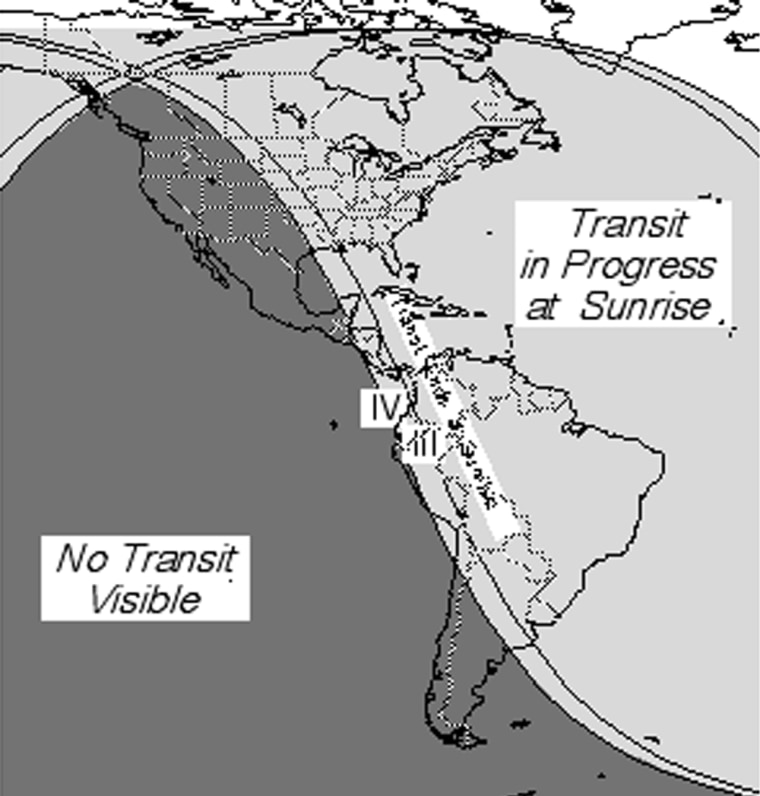

The sun will be above the horizon for the entire transit for most of Europe and Asia, as well as from the eastern two-thirds of Africa. The sun sets with Venus still on its disk for Indonesia, Japan and Australia.

The event is already in progress when the sun rises across much of eastern Canada and the central and eastern United States. For the contiguous United States, locations east of a line running roughly from Havre, Mont., south and east to Galveston, Texas, should be able to see a part of the transit. Those to the west of this line are left out.

States that will miss the transit include Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Montana, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington and Wyoming.

The end of the transit may also be observed from the islands of the Caribbean, as well as much of the northern and central portions of South America.

Anyone wishing to see the event needs to know when it occurs in local time. And skywatchers must employ safe viewing techniques to avoid eye damage. Never look directly at the sun without proper filters.

What you'll see

Depending upon where one is located, Venus’ transit will begin within several minutes of 05:13 GMT at every site from which it is visible. That corresponds to about 1:13 a.m. in the Eastern time zone of the United States. It will end approximately within several minutes of 11:26 GMT, or about 7:26 a.m. ET. (Check out Space.com's Venus Transit Headquarters. for detailed timetables.)

For the central and eastern United States, as well as for much of northern and eastern Canada, the sun rises with Venus already on its disk. As soon as they have come above the east-northeast horizon, the planet should be recognizable near to the sun’s right limb as a small, black, sharp-edged spot.

As you watch, the gradual travel of this dot will bring it to the sun’s right edge. This will be an especially interesting time. The moment when the two disks become internally tangent — that is, when the black disk of Venus first touches the Sun’s outer limb — is known as Contact III. For most U.S. and Canadian locations where the transit will be visible, Contact III should occur within about a minute of 7:05 a.m. ET.

Egress then lasts about 20 minutes; that’s how long it will take for the black disk of Venus to move completely off the sun’s face.

Finally, the last notch in the sun’s limb disappears, marking Contact IV, which should occur within a minute of 7:25 a.m. ET. With a large, filtered telescope at high power (see the important warning below for how to do this safely), see if you can time when Venus’ edge crosses the limb of the sun.

At egress, when Venus has partially moved off the sun’s disk, a thin circle of light around the planet may appear. This is a well-known effect of Venus’ atmosphere, which was observed as long ago as the 1761 transit by the Russian scientist M.V. Lomonosov.

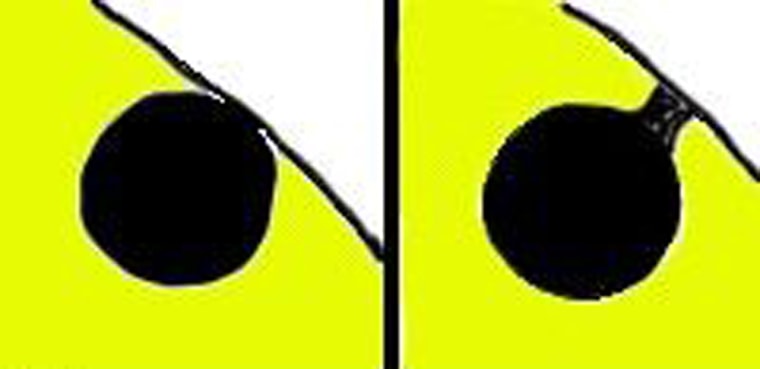

And just moments before interior contact actually takes place, viewers may see the silhouette of Venus become suddenly connected to the sun’s limb by a dark ligament – like a drop of water just before separating from a faucet. Another way to describe it is that the planet will seem attached to the sun’s limb by a thin black column or thread.

This optical illusion is known as the "black drop effect." Its cause is believed to the combination of local atmospheric shakiness and blurring (known as "seeing" by astronomers) and telescope diffraction, in conjunction with the dark disk of Venus interacting with the limb darkening of the sun’s outer edge.

Important warning

Unlike the transits of Mercury, those of Venus are visible with the unaided eye; the planet appears as a distinct, albeit tiny, black spot with a diameter just one-32nd that of the sun. This size is large enough to readily perceive with the naked eye.

But prospective observers are warned to take special precautions (as with a solar eclipse) in attempting to view the silhouette of Venus against the brilliant disc of the sun.

Never look directly at the sun. Permanent eye damage can result. Instead, proper telescope filters or protective glasses from reputable astronomy dealers should be used.

Observing a transit is a lot like studying sunspots because, after all, you are looking at a dark spot on the sun. But trying to see a transit is also like trying to view a solar eclipse. You have to be ready at a particular time, and you may have to travel far from home. Your exact location, however, is much less critical than it is at a total solar eclipse. For those in North America, where this will be an early morning event, your observing site should have a low horizon to the east-northeast.

Check the sun’s rising point a day or two beforehand, to verify that trees or buildings do not block your view. This is especially important in North America, where the event will be over shortly after sunrise. As Venus moves across the face of the sun, it will appear absolutely jet-black in contrast to the lighter gray of any sunspots that may also be present on the solar disk.

Safe viewing methods

By far the safest way to view the transit is to construct a "pinhole camera."

A pinhole or small opening is used to form an image of the sun on a screen placed about three feet behind the opening.

Binoculars or a small telescope mounted on a tripod can also be used to project a magnified image of the sun onto a white card. Just be sure not to look through the binoculars or telescope when they are pointed toward the sun! Venus should appear as a tiny, distinct dot on the projected image.

A variation on the pinhole theme is the pinhole mirror. Cover a pocket-mirror with a piece of paper that has a ¼-inch hole punched in it. Open a sun-facing window and place the covered mirror on the sunlit sill so it reflects a disk of light onto the far wall inside. The disk of light is an image of the sun’s face.

The farther away from the wall is the better; the image will be only 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) across for every 9 feet (2.75 meters) from the mirror. Modeling clay works well to hold the mirror in place.

Experiment with different-sized holes in the paper. Again, a large hole makes the image bright, but fuzzy, and a small one makes it dim but sharp. Darken the room as much as possible. Be sure to try this on days prior to the event to make sure the mirror’s optical quality is good enough to project a clean, round image. Of course, don’t let anyone look at the sun in the mirror.

Acceptable filters for unaided visual solar observations include aluminized Mylar. Some astronomy dealers carry Mylar filter material specially designed for solar observing. Also acceptable is shade 13 or 14 arc-welder’s glass, available for just a few of dollars at welding supply shops.

It also used to be widely advertised that two layers of fully exposed and developed black-and-white negative film was safe. This is still true, but only if the film contains an emulsion of silver particles. Beware: Some black-and-white filmsnow use black dye, which is no longer safe. It is always a good idea to test your filters and/or observing techniques before eclipse day.

Projecting the sun’s magnified image through a telescope and onto a white card or screen is relatively safe and can be used for group viewing.

For serious transit observing, a telescope with a full-aperture solar filter is much better. Such filters are attached on that side of the telescope that is facing the sun, not the side facing your eye. This will cause most of the sunlight to be filtered out before entering your telescope.

The transit should be watched only with an appropriate solar filter — a solar filter that is sold by a reputable outlet of astronomical equipment. If your telescope comes with a filter that screws into the eyepiece, discard it immediately! Such filters have been known to crack under the intense heat of the sun’s magnified image.

Lastly, never look at the sun directly through your telescope, even through your smaller, finder scope. It is strongly advisable to cover the finder scope before the transit, so as to avoid looking through it accidentally.

What not to do

Unacceptable filters include sunglasses, color film negatives, black-and-white film that contains no silver, photographic neutral-density filters and polarizing filters. Although these materials have very low visible-light transmittance levels, they transmit an unacceptably high level of near-infrared radiation that can cause a thermal retinal burn. The fact that the sun appears dim, or that you feel no discomfort when looking at the sun through the filter, is no guarantee that your eyes are safe.