The Supreme Court dealt a setback to the Bush administration on Monday, ruling that both U.S. citizens and foreign nationals seized as potential terrorists can challenge their treatment in U.S. courts.

The court refused to endorse a central claim of the White House since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001: That the government has authority to seize and hold suspected terrorists or their protectors and indefinitely deny them access to courts or lawyers while interrogating them.

The court did back the administration in one important respect, ruling that Congress gave President Bush the authority to seize and hold a U.S. citizen, in this case Louisiana-born Yaser Esam Hamdi, as an alleged enemy combatant.

Foreigners gain access to U.S. courts

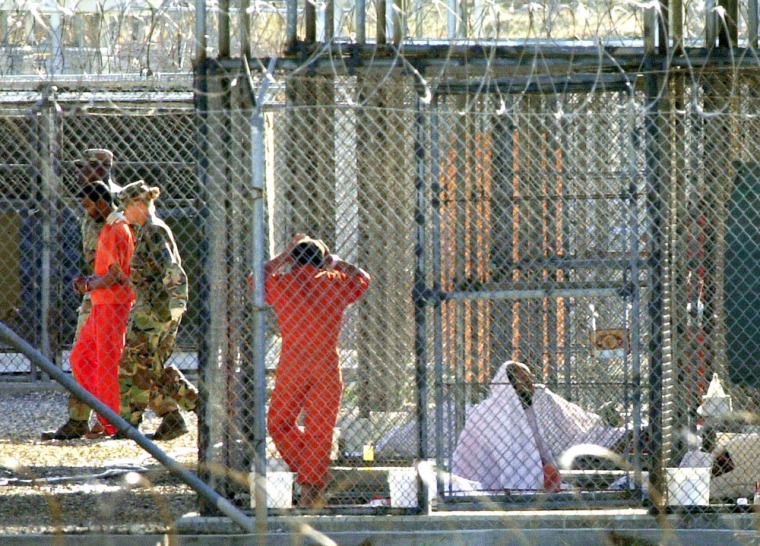

That bright spot for the administration was almost eclipsed, however, by the court's ruling that Hamdi can use American courts to argue that he is being held illegally. Foreigners held at a Navy prison camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, can also have their day in U.S. courts, the justices said.

Ruling in the Hamdi case, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor said the court has “made clear that a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to the rights of the nation's citizens.”

But while she said Hamdi was entitled to a hearing, she suggested the court majority could accept his not getting all the protection he'd get in a federal district court hearing.

O'Connor said that one place to hear Hamdi's side of the story might be before a military tribunal. "The standards we have articulated could be met by an appropriately authorized and properly constituted military tribunal,” she wrote.

Steven Shapiro, legal director of the ACLU, called the rulings “a strong repudiation of the administration's argument that its actions in the war on terrorism are beyond the rule of law and unreviewable by American courts.”

The vote in the Guantanamo case was 6-3, with the court’s three most conservative members dissenting.

The justices splintered in the Hamdi case, with a different lineup of six justices voting to throw out a lower court ruling in the government’s favor and allow Hamdi another chance to air his claims. Three justices disagreed with that outcome for varying reasons.

Perhaps more significantly, eight of the nine justices sided against the Bush administration on some grounds. Only Justice Clarence Thomas, by many measures the court’s staunchest conservative, found no fault with the administration.

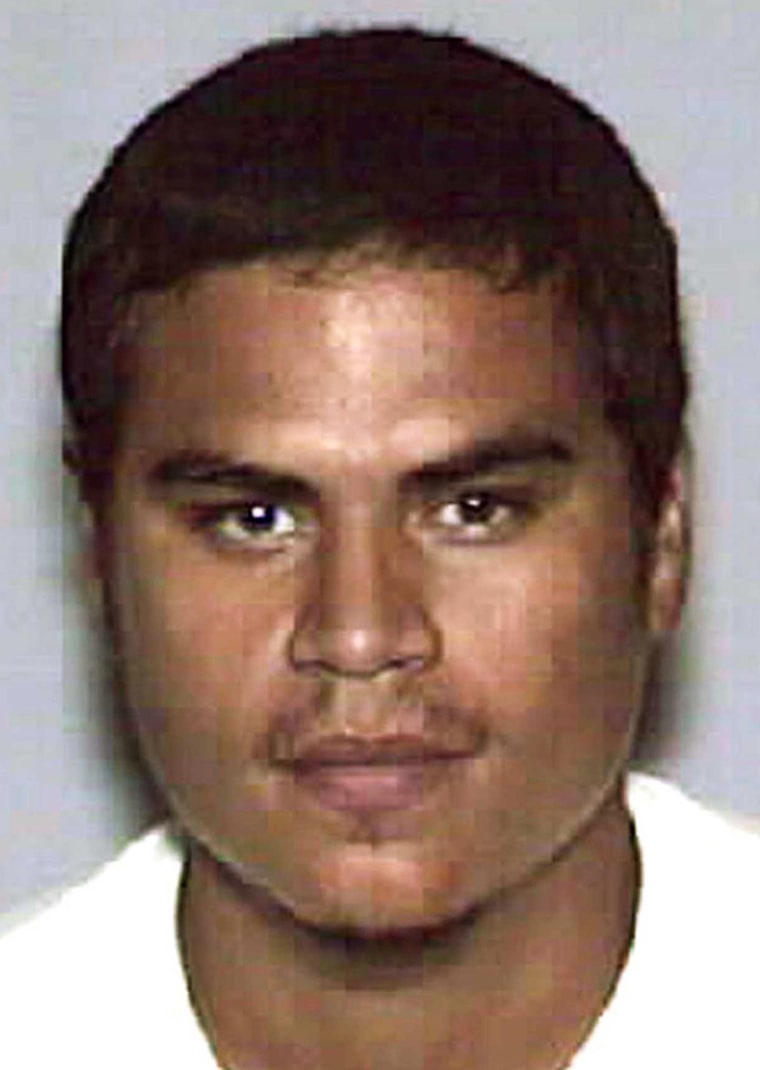

The court sidestepped a third major terrorism case, dismissing a lawsuit filed on behalf of American detainee Jose Padilla on a technicality.

The court, in a 5-4 ruling, said that Padilla petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus — asking a judge to determine whether or not he was imprisoned lawfully — in New York, but was no longer in the state by the time the court considered his case. The justices said he should have brought the case instead in South Carolina, where he has been held in a U.S. military jail as an “enemy combatant.”

Dissenters: ‘Essence of a free society’ at stake

The four dissenters said they would have decided the heart of the case. “At stake in this case is nothing less than the essence of a free society,” wrote Justice John Paul Stevens.

The court left hard questions unanswered in all three cases.

The administration had fought any suggestion that Hamdi or another U.S.-born terrorism suspect could go to court, saying that such a legal fight posed a threat to the president's power to wage war as he sees fit.

"We have no reason to doubt that courts, faced with these sensitive matters, will pay proper heed both to the matters of national security that might arise in an individual case and to the constitutional limitations safeguarding essential liberties that remain vibrant even in times of security concerns," Justice Sandra Day O'Connor wrote in the Hamdi case.

O'Connor said that Hamdi "unquestionably has the right to access to counsel."

The court threw out a lower court ruling that supported the government's position fully, and Hamdi's case now returns to a lower court.

O'Connor was joined by Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Anthony Kennedy and Stephen Breyer in her view that Congress had authorized detentions such as Hamdi's in what she called very limited circumstances.

Lawyers rush to get access

Lawyers for foreign terrorism suspects at the U.S. military base in Cuba plan to ask this week for access to their clients, armed with the Supreme Court ruling that the prisoners can fight their detention in court.

Lawyers from the Center for Constitutional Rights, which brought the case to the high court, said they would seek access to their clients within the week.

“We will be asking for access to our clients and for information about their mental and physical health,” said attorney Joseph Margulies. “We will move very quickly to seek access to our clients, something that has been denied them from the beginning of this litigation.”

The center wants to talk to the two prisoners it represented in the Supreme Court case. Dozens of others have also asked the center act on their behalf, and lawyers will file requests for access to them as well.

Margulies said the government now has the responsibility of giving specific reasons for the detention of each prisoner. “At a minimum, they must now come forward with some evidence,” he said. “You don’t simply hold people in a lawless void based on nothing more than executive say-so.”

Extent of presidential authority at issue

Congress voted shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks to give the president significant authority to pursue terrorists, but Hamdi's lawyers said that authority did not extend to the indefinite detention of an American citizen without charges or trial.

Two other justices, David Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, would have gone further and declared Hamdi's detention improper.

Still, they joined O'Connor and the others to say that Hamdi, and by extension others who may be in his position, are entitled to their day in court. Only Justice Clarence Thomas dissented on that point.

Hamdi and Padilla are in military custody at a Navy brig in South Carolina. They have been interrogated repeatedly without lawyers present.

In the Guantanamo case, the court said the Cuban base is not beyond the reach of American courts even though it is outside the country. Lawyers for the detainees there had said to rule otherwise would be to declare the Cuban base a legal no-man's land.

Ruling applies only to Guantanamo detainees

The high court's ruling applies only to Guantanamo detainees, although the United States holds foreign prisoners elsewhere.

The Bush administration contends that as "enemy combatants," the men are not entitled to the usual rights of prisoners of war set out in the Geneva Conventions. Enemy combatants are also outside the constitutional protections for ordinary criminal suspects, the government has claimed.

The administration argued that the president alone has authority to order their detention, and that courts have no business second-guessing that decision.

The case has additional resonance because of recent revelations that U.S. soldiers abused Iraqi prisoners and used harsh interrogation methods at a prison outside Baghdad.

For some critics of the administration's security measures, the pictures of abuse at Abu Ghraib prison illustrated what might go wrong if the military and White House have unchecked authority over prisoners.

At oral arguments in the Padilla case in April, an administration lawyer assured the court that Americans would abide by international treaties against torture, and that the president or the military would not allow even mild torture as a means to get information.